Known as one of the most popular Croatian writers, Marija Jurić ‘Zagorka’ was born on this day in 1873. She was an ardent patriot, a pioneer feminist, an accomplished political journalist and a prolific fiction writer, who sadly didn’t live to see her work receive critical acclaim. Her life story, marked by adversity and isolation, reads like a novel in itself: who was this great woman?

Marija Jurić was born into a family she would later describe as wealthy, but miserable. She was educated by private tutors from an early age, as her father managed the estate of Baron Geza Rauch who saw to it that the girl studied alongside his own children. After she finished elementary school in Varaždin as a bright pupil who shower great promise, Baron Rauch offered to pay for her to continue her education in Switzerland. Her father was in favour of the idea, but her mother objected and Jurić ended up going to an all-girls secondary school in Zagreb.

Instead of being allowed to pursue her interest in journalism and nurture her apparent writing talent, the girl was forced into an arranged marriage. At the age of 18, and again at the insistence of her mother, Jurić married a Slovak-Hungarian officer Andrija Matray who was 17 years her senior.

They moved to Hungary, and the marriage unsurprisingly turned out to be an unhappy one. As a fervent nationalist, Matray wouldn’t allow her to write unless she agreed to adopt a pro-Hungarian stance, a prospect unacceptable to Jurić who on her part was extremely devoted to her home country. He was also abusive enough to cause the young woman to suffer a mental breakdown during the three years they lived together. Later on, she’d flee back to Croatia and legally divorce Matray, but as her mother testified against her in court – mother of the year, that one – she ended up not getting alimony from Matraja nor her personal belongings back.

This was a turning point for Jurić, who then decided to break all ties with her family, settled in Zagreb and went to pursue a career in journalism. Quite a bold move for a woman at the end of the 19th century, and her choice to live a life outside of the wife-and-mother narrative was taken by some as a sign that she was mentally unstable.

At the age of 23, she started working for the newspaper Obzor (Horizon), where the board of directors at first only assigned her proofreading work because she was a woman. Later on, at the insistence of bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer, she was given journalist assignments, but had to work in a separate room, isolated from the rest of the staff.

She powered on, starting as a writer who wasn’t allowed to sign her pieces to eventually grow into a reputable journalist who reported on all major political events in Croatia and the region. She also stood in as the editor in chief of Obzor for five months during which the former editor and his deputy were imprisoned. As she later organised demonstrations against the ban Khuen-Héderváry who was carrying out an oppressive magyarization of Croatia at the time, Marija was imprisoned as well and served ten days in solitary confinement.

In her career as a journalist, she wrote for numerous papers and journals, but also started a few of her own: Zabavnik in 1917, Ženski list (Women’s Paper) in 1925, and Hrvatica (Croatian Woman) in 1939. As a feminist and a relentless advocate for women’s rights, she covered the subject extensively as a journalist and gave public lectures all over the region, eliciting contempt and ridicule from her predominantly male colleagues.

All the while, she wrote fiction as well. Encouraged by bishop Strossmayer, she wrote her first novel in her 30s, going on to publish two dozen novels and several plays.

Written under the pen name Zagorka, her work is best described as historical fiction with elements of romance, adventure and mystery. A master of narrative, she was an extremely prolific author, largely inspired by Croatian history which is reflected in her most popular novels: Daughter of the Lotrščak, The Flaming Inquisitors, the 7-volume saga The Witch of Grič, and above all Gordana, the longest novel in the history of Croatian literature, totaling nearly 9000 pages in twelve volumes.

The readers didn’t mind the intimidating page count; on the contrary, Zagorka’s work was immensely popular in her time and always well received by her readership. Perhaps that’s why the critics couldn’t stand her: she was constantly put down by her contemporaries, singled out and ridiculed for being an author of ‘trivial pulp literature’.

Sadly, the tide only turned after her death in 1957. Her work in journalism was the first to receive acclaim in the 60s, followed by valorisation of her fiction in the 80s.

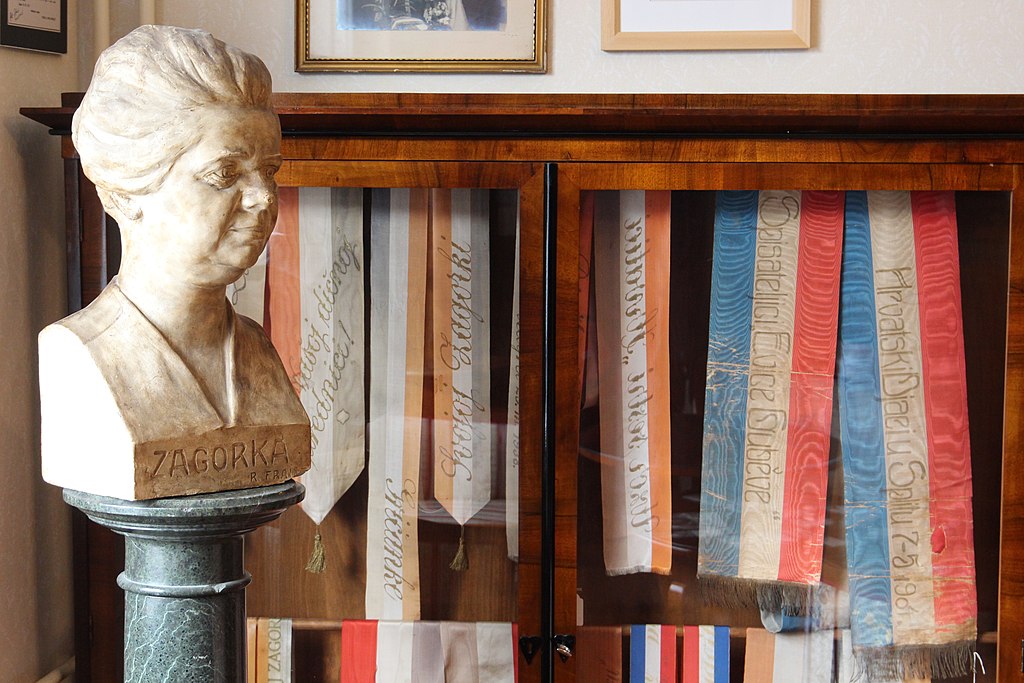

Memorial Apartment of Marija Jurić Zagorka

Memorial Apartment of Marija Jurić Zagorka

Nowadays, Zagorka is known as one of the most popular Croatian writers of all time, and her legacy is held in high regard. The apartment she lived in was purchased by the City of Zagreb and turned into the Memorial Apartment of Marija Jurić Zagorka, run by the NGO Centre for Women’s Studies Zagreb.

The Centre organises an annual event named Days of Marija Jurić Zagorka, and the Croatian Journalists’ Association’s award for excellence in journalism bears her name as well.

Monument to Marija Juric Zagorka in Zagreb

Monument to Marija Juric Zagorka in Zagreb

In 1995, renowned Croatian writer Pavao Pavličić published a work entitled Hand-kiss: Letters to Famous Women. In it, he speaks of the lack of full-blooded narratives in Croatian fiction at the time, a lack of authors who could grab and hold the reader’s attention like Zagorka was able to do.

Perhaps the most poignant statement about the magnitude of Zagorka’s legacy comes from Pavličić, as he addresses her directly:

You were ahead of your time, and perhaps this would finally be the right time for you, as we are only now aware how much we need that which you could have given us.