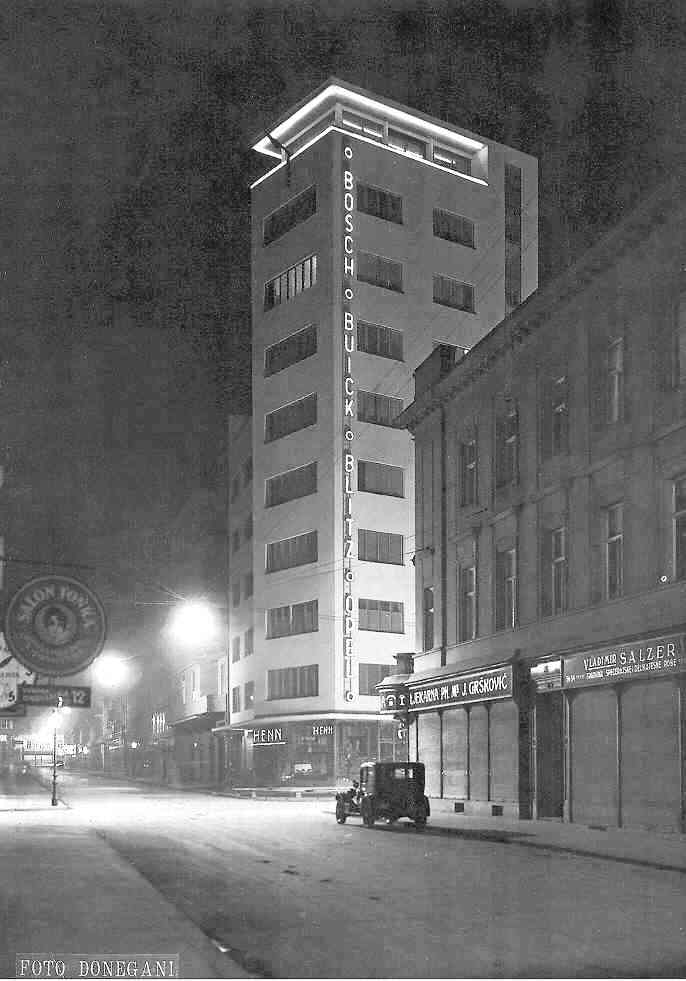

It was 1933, Zagreb had around 230,000 inhabitants, Dolac and Zagreb Stock Exchange palace had just been built by modernism pioneer Viktor Kovačić. There was an unprecedented construction site, at which Zagreb’s first skyscraper was built in a record 79 days.

Although some other buildings were mentioned as first skyscrapers, the title belongs to the corner nine-storey building built on the corner of Masarykova and Gundulićeva Streets under the watchful eye of architect Slavko Löwy. This was a turning point in the career of young and ambitious Dresden Royal Technical College graduate, and a new symbol of industrial development and new housing concept in Zagreb.

Eugen Radovan, a wealthy merchant and exclusive representative of the companies Bosch, Blitz and Opel, decided to build a business complex in the city. It was supposed to be a four-storey building the attire and impressive outlook of which would match the reputation of brands sold in it. Radovan purchased land downtown for this purpose, but city planners demanded that 36 square meters be given to the city for the traffic area that was already marked in the urban plan of the city.

Löwy found a solution to the problem – he built upwards, to the general consternation of urban planners and enthusiasm of the public. The corner skyscraper is divided into a five-storey business complex in extends Gundulićeva Street and a residential nine-storey building in Masarykova Street.

The construction provoked strong reactions. Although the media reported on this as commendable representation of cosmopolitan values, correspondence between the architect and the city’s urban planners shows that the intervention into the old town has always caused controversy.

Wikimedia commons

First of all, due to “reduced visibility” Löwy was asked that the corner where two parts of the building merged be made blunter, and flat roof was also not approved of. In the end Löwy won – after the skyscraper was finished, instead of receiving a substantial amount of money, he decided to move into the studio apartment on the ninth floor which he designed exclusively for himself.

A year later, in 1934, Löwy founded his own architectural studio and moved it into his glass nest. This is where he worked and lived until the war because he felt that 40 square meters of space was more than enough for his professional and private life.

He thought that the only way to be completely true to the concept of studios, a trademark of his residential architecture projects, was by living in one.

Wikimedia commons