March the 29th, 2020 – Professor Igor Rudan is the Director of the Centre for Global Health and the WHO Collaborating Centre at the University of Edinburgh, UK; he is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Global Health; a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and one of the most highly cited scientists in the world; he has published more than 500 research papers, wrote 6 books and 3 popular science best-sellers, developed a documentary series “Survival: The Story of Global Health” and won numerous awards for his research and science communication.

The perception of the COVID-19 pandemic in my homeland Croatia has been based on two main sources of information over the past three weeks. On the one hand, our Civil Protection Headquarters, as well as all of the experts and scientists to whom media space has been provided, called for caution, but without any panic. They emphasised that this was not a cataclysm, but an epidemic involving a serious respiratory infectious disease. The cause of this disease is the new coronavirus, for which we don’t have a vaccine. Therefore, it can be expected that the disease will be very dangerous for the elderly and to those who are already ill. So, it was an unknown danger worthy of caution, but our epidemiologists remained calm. They knew that they would be able to estimate the epidemic’s development using figures, and then control the situation with anti-epidemic measures, and through several lines of defense.

On the other hand, we also followed the events in Italy. From there, day after day, apocalyptic news came, with incredibly large numbers of infected and dead people. Daily reports from Italy seemed completely incompatible with what the experts and scientists in Croatia were saying. Some have concluded that a scenario similar to that in Italy, if not worse, is inevitable for Croatia. The population was in a very confusing situation.

In this text, I will try to penetrate the very core of the “infodemia” that has been present in the media across many European countries, as well as on social networks, over the past three weeks. I will explain how that disturbing situation arose and offer a scientific explanation for it. This seems important to me at this point, because the Italian tragedy with the COVID-19 epidemic has, unfortunately, hindered the credible and scientifically based communication of the epidemiological profession to the population of Croatia.

In my article “20 Key Questions and Answers on Coronavirus” posted on the 9th of March, 2020 on Index.hr, in answer to question number 18, “With the effectiveness of quarantine in China, can we draw some lessons from this pandemic?”, I stated:

“If the virus continues to spread throughout 2020, it will demonstrate in a very cruel way how well the public health systems of individual countries are functioning… These will be very important lessons in preparation for a future pandemic, which could be even more dangerous.’’

We’re now slowly entering a phase where many countries have been exposed to the pandemic for long enough. Thanks to this, we can make some first estimates of their results. From these days up until the end of the pandemic, we’ll see that COVID-19 will divide the world into countries that have relied on epidemiology and followed the maths and the logic of the epidemic, as well as those in which this isn’t the case, and many sadly, probably quite unnecessarily – will suffer.

An epidemic is a serious threat to entire nations, during which residents’ interest in other topics may vanish quite rapidly. We could see that happening quite clearly in the past several weeks. The task of epidemiologists is to constantly have tables in front of them with a large number of epidemic parameters, reliable field figures and formulas to monitor the epidemic’s development, and to know the ‘’laws’’ of epidemics, in order to organise the implementation of anti-epidemic measures in a timely manner and thus protect the population.

Now, let’s look at the countries that we can already point out as being successful in their response to this new challenge. First and foremost, there’s China. It has completely suppressed the huge epidemic in Wuhan, which spread to all thirty of its provinces. In doing so, it relied on the advice of its epidemiologic legend, 83-year-old Zhong Nanshan. Twenty years ago, Nanshan gained authority by suppressing SARS. Although surprised by the epidemic, they managed to suppress COVID-19 throughout China through expert and determined measures. They did so over just seven weeks, with the death toll eventually coming to a halt at less than 5,000. By comparison, it would be as if the number of deaths in Croatia as a result of this epidemic was kept at around 14 in total.

Furthermore, if at some point you find yourself caught up in the uncertainty surrounding the danger of COVID-19, you will easily be able to find out the truth if you look at the state of things in Singapore. Despite intensive exchanges of people and goods with China since the outbreak of the epidemic, Singapore has a total of 732 infected people as I am writing this article, with two dead and 17 more in intensive care. This city-state has the ambition to be the best in the world in all measurable parameters. From this, it must be concluded that the developments in Singapore are a likely reflection of the real danger of COVID-19. However, this is true of countries that base their regulation on knowledge, technology, good organisation and general responsibility. The situation in Singapore, therefore, is an indicator of the effects of the virus on the population, to the extent that it is truly unavoidable.

Any deviation towards something worse than the Singaporean results will be less and less of a consequence of the danger of the virus itself, and increasingly attributable to human omissions. In doing so, human errors that can lead to the unnecessary spread of the infection are: (1) the epidemiologists’ omission to properly understand the epidemic parameters; (2) decision-makers’ reluctance to make decisions based on the recommendations of epidemiologists; and (3) the irresponsible behaviour of the population in complying with government instructions.

To confirm the statements about Singapore, let’s look at the current situation in other countries that rely on knowledge and expertise and have good organisation. They were also the most common destinations for the spread of the epidemic from China in the first wave: Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. There were only 519 infected people in Hong Kong at the time of writing this article, with 4 deaths and 5 more people in a serious condition; in Japan 1,499 were infected, 49 were dead and 56 were in a serious condition; in South Korea, which had a severe epidemic behind its first line of defense, 9,478 were infected, 144 died and 59 were seriously ill; in the United Arab Emirates, 405 were infected, 2 died and 2 were seriously ill; and in Qatar, 562 were infected, 6 were seriously ill, and still no one had died from COVID-19.

Fortunately, Croatia is now up there with all of these countries, with 657 infected, 5 dead and 14 more seriously ill. As you can see pretty clearly from all of these figures, in countries that rely on knowledge and the profession and properly applied anti-epidemic measures, COVID-19 is a disease that should not endanger more than 1 percent of all infected people. This conclusion can be reached by considering that the information on the “https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus” page is based on positive tests, and not on everyone who is actually infected.

What, then, is happening in Italy, as well as in Spain, but to a good extent also in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark and Portugal? I did not include Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States in this group of countries for now. This is because at least for some time during the epidemic, they have clung to the idea of intentionally letting the epidemic develop and infect at least part of the population, so I will refer to their strategies and their results in one of my following texts.

Given all of the previous examples of a successful epidemiological response, and what is now practically the coexistence of people with the new coronavirus in Asia’s most developed countries, how is it possible for Italy to have nearly 85,000 infected people and over 9,000 deaths at the time of this article? How is it possible that Spain has 72,000 infected people and more than 5,600 deaths, and France has almost 33,000 infected people and 2,000 deaths? Or that even Switzerland, which everyone would expect to see among the most successful countries in any of these world rankings, could already have 13,250 infected people and 240 deaths, with 203 more critically ill people? The causes of all of this are, however, becoming increasingly clear to science.

First of all, there was probably a premature relaxation around the real danger of COVID-19 in Europe. The epidemic development by the end of February was already quite similar to the one seen previously with SARS and MERS. Even then, the primary focal point was suppressed, and in more than 25 countries, the virus was then stopped at the front lines of defense. By the end of February 2020, it was already clear in the case of COVID-19 that it would be successfully suppressed in its primary focal point – Wuhan. It was also already stopped at the front lines of defense in another thirty Chinese provinces and surrounding countries in Asia. Then, on February the 28th, the first estimates of death rates were published, saying that it was a disease with a death rate significantly lower than that of SARS and MERS. At that time, it was reasonable to expect that the epidemic could soon be

stopped. As a result, the World Health Organisation delayed the declaration of a pandemic until March the 11th, and the world stock markets increased by about 10 percent from February the 27th to March the 3rd. But for any unknown virus, premature relaxation is very dangerous, as will be shown later with COVID-19.

Secondly, several investigative journalists reported that it may be possible that the phenomenon of the mass immigration of Chinese workers to northern Italy may have contributed to the early introduction and spread of the virus in Europe. Tens of thousands of Chinese migrants work in the Italian textile industry, producing fashion items, leather bags and shoes with the brand “Made in Italy”. Partly as a result of this development, direct flights between Wuhan and Italy were introduced. Some estimates say that Italy has allowed up to 100,000 Chinese workers, initially from Wenzhou, but later also likely from Wuhan and other cities neighbouring Shanghai, to work in those factories. Some of them may have been there illegally and worked in conditions where they were cramped together, which would help the virus to spread easily. Reporter D. T. Max wrote about this phenomenon in the New Yorker magazine back in April 2018. After their return from the Chinese New Year celebrations in mid-February, the Italian authorities rigorously checked these workers on their “first line of defense” at the airports. But rumours began spreading that some had begun to enter Italy but were bypassing Italian airports. Instead, they were going through other airports in the EU where controls weren’t as tight. So, the COVID-19 epidemic was likely triggered behind the back of the Italian “first line of defense“, which remained unrecognised in the first few weeks.

Third, many infected people from northern Italy spent their weekends at European ski resorts. Although we don’t know if the arrival of the warmer weather will stop the transmission of coronavirus, what we can assume is that the cold helped it to spread. That is why European ski resorts became real nurseries of coronavirus in late February and in early March. In this way, more infected people emerged behind the front lines of defense in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Spain and Portugal. Their first lines of epidemiological defense focused on air transport from Asia, not on their own skiing ‘’returnees’’, where indeed no one would expect a large number of Chinese people from Wuhan to be.

Fourth, although Spain may not have had as many skiers as other European countries in this cluster, the virus may have been introduced to them through a “biological bomb”. On February 19th, a Champions League football match was held between Atalanta and Valencia. Atalanta is a team from a small city of Bergamo, Italy, which has 120,000 inhabitants. This was possibly the biggest game in Atalanta’s history, as it progressed through group stages to the last 16 in the European Champions League. The local stadium was not large enough for everyone who wanted to attend the game, so it was moved to a large San Siro stadium in Milan.

The official attendance was 45,792, meaning that a third of Bergamo’s population, with around 30 busses, travelled from Bergamo to Milan and then wandered the streets of Milan before the game. Unfortunately for Spain, nearly 2,500 Valencia fans also traveled to the match. As Atalanta scored four goals, a third of Bergamo’s population was hugging and kissing in the cold weather four times and spent the day closely together. This is likely why it became the worst-hit region of Italy by some distance. Unfortunately, at least a third of the Valencia football squad also got infected with a virus and later played Alaves in the Spanish league, where more players of that team got infected. This football game has certainly contributed to the virus making its way to Spain.

Fifth, it’s very important for the early development of the epidemiological situation in each country to look at which subset of the population the virus has spread among. Northern Italy has a very large number of very old people. In the early stages of the epidemic, the virus began to spread in hospitals and retirement homes. They didn’t have nearly enough capacities to assist in the severe cases. Among already sick, elderly and immunocompromised people, the virus spread more easily and faster and had a significantly higher death rate. In some other countries, such as Germany, most of the patients in the early stages were between the ages of 20 and 50, and were returning from skiing trips or were business people. Therefore, such countries have a significantly lower death rate among those first infected.

Sixth, and what the most important thing needed to understand the current situation in Italy is, must have been either the omission of Italian epidemiologists to monitor the mathematical parameters of the epidemic, or perhaps their lack of clear communication of the dangers to those in power in northern Italy, or the indecisiveness of those in power to adopt isolation measures for the population. It is difficult at this time to know which of these three causes is the most important, and a combination of all of them is entirely possible. However, I will explain the nature of the omission, as it largely explains the terrible figures on infections and deaths that are being reported from Italy on a daily basis.

To understand the story of this tragedy in Italy, we must first return to Wuhan. When the epidemic broke out, the Chinese first had to isolate the virus. Then, they needed to read its genetic code and develop a diagnostic test. It all took time, as the epidemic spread rapidly throughout the city. When they began testing for coronavirus, between January the 18th and the 20th, they had double-digit numbers of infected people. Those numbers apparently stagnated, so the epidemiologists didn’t know what that might mean. But on the 21st of January, the number of newly infected people jumped to more than 100. On the 22nd of January, it jumped to more than 200. This was a clear signal to Chinese epidemiologists that an exponential increase in the number of infected people was occurring. At that time, they had nothing further to wait for, or to think about. If the virus breaks through the first line of defense – and the Chinese didn’t even have any, since the epidemic started there – then a quarantine measure needs to be triggered. This prevents the virus from spreading further and creating a large number of infected people through exponential growth.

After such a sudden declaration of quarantine in Wuhan, the huge epidemic wave of the Chinese had actually just begun to show. Everyone who was already infected began to develop the disease in the next few days. The maximum daily number of new infected cases was reached on the 5th of February. On that day alone, as many as 3,750 new patients were registered in Wuhan. Remember, this means that the jump from about 125 to about 250 registered newly infected people signals to epidemiologists that we should expect an epidemic surge in 14 days, with as many as 3,750 newly infected people in one single day.

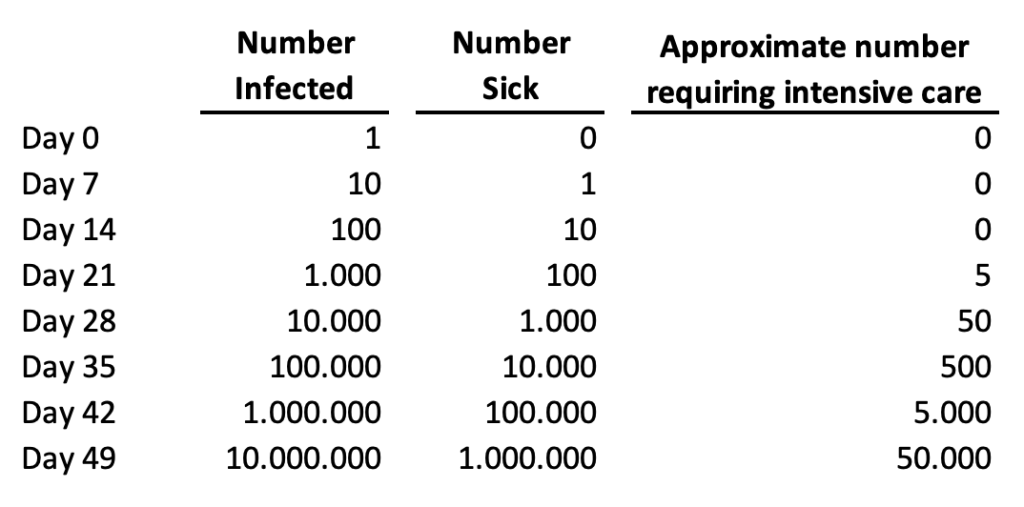

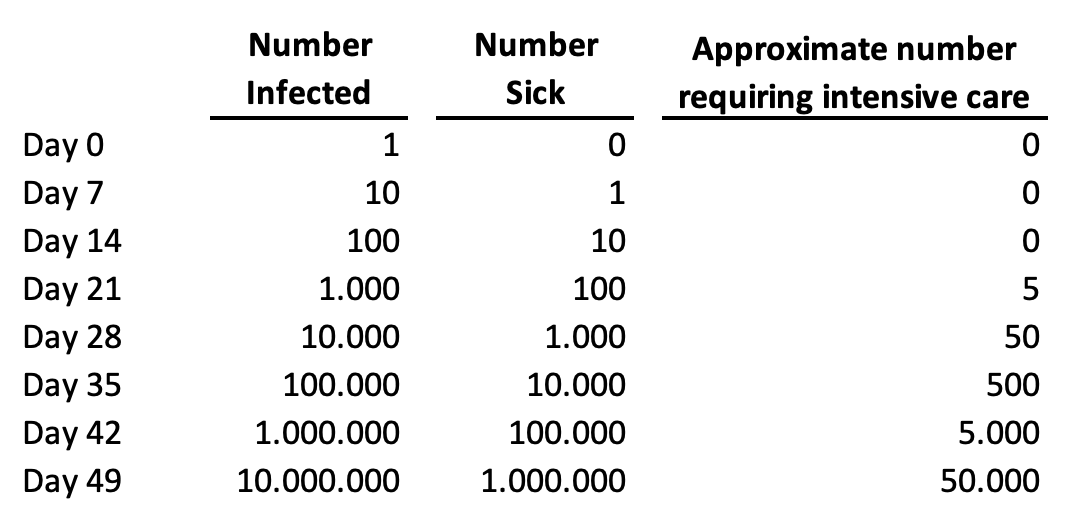

Let’s now explain this “time delay” between people getting infected with the virus and the health system being able to detect all those infected people based on their symptoms. The new coronavirus kills primarily because it spreads incredibly quickly among humans. As a result, it creates a gigantic number of infected and sick people in a very short time period. Among those who are sick, about 5 percent will require hospital care. If all of them could receive optimal care, we’d be able to save nearly everyone. But if they all get very sick at the same time, we can’t offer them adequate care and nearly all of the critical cases will die. This is the primary way in which this virus kills so many people. It is illustrated in a very simple way in this table, based on day-to-day growth in a number of cases by 26 percent, which was a very realistic scenario for most EU countries:

TABLE ONE: The dynamics of the epidemics of COVID-19 in any given country, based on a realistic scenario of about 26 percent of day-to-day growth of the number of cases:

With this in mind, let’s now look at the Italian reaction to their own epidemic. In the early stages of infection spreading in a country, one or two infected persons are usually detected daily. Personally, I advised the Croatian authorities and public to start seriously thinking about social exclusion measures when they noticed the first notable shift from the first 10 confirmed infections towards the first 20 infected people.

On March the 12th, I posted a Facebook status entitled “Contrast is the mother of clarity”, which was viewed and shared by many thousands of my fellow Croatians who have been following my popular science series on the pandemic – “The Quarantine of Wuhan”. This status has also been shared by many online and printed newspapers and media, including radio stations. In that status, I suggested that Croatia should consider a large quarantine because we had already jumped from 14 to 19 infected people the day before, but to also weigh this against the economic implications and their expected effect on health. The very next day, a decision was made to close the schools.

That meant that, up to that point, Croatia completed two of the most important tasks in this pandemic. The first task was to hold its first line of defense. This was being achieved through the identification of infected cases imported from other countries and their isolation, and that of all of their contacts. Croatia completed this first task better than the other EU countries did, based on an average percentage increase of cases between the 3rd of March and the 17th of March. Then, from March the 13th, Croatia also began to introduce social exclusion measures at the right time, thus successfully carrying out the second key task in controlling its own epidemic. Many credits go to its epidemiologists who work at the Croatian Institute for Public Health.

But, what went wrong with these two measures in Italy? On the 21st of February, their number of confirmed infected cases jumped from 3 to 20. As Italy is a more populous country than Croatia, it might have still been too hasty to send all of Lombardy into quarantine based on this. But on the 22nd of February, the jump was from 20 to 62 cases, and they already needed to think very seriously about it. A couple of days later, on the 24th of February, they reached a situation very similar to that in Wuhan as the number of confirmed infections jumped from 155 to 229. This was particularly worrying because they didn’t seem to be performing many tests proactively at that time, either.

That “jump” from 155 to 229, in combination with the Wuhan experience, should have suggested that they would have at least 50,000 infected people under the predicted curve of the epidemic wave and they were just seeing its early beginning. And that many infected people would mean that about 2,500 affected would require intensive care units. At the time, Lombardy had only about 500 such units in government/state facilities and another 150 in private healthcare facilities. As early as 24th of February it was clear that there would be many deaths in Lombardy weeks later. With epidemics, everything goes awry because the infected get sick a week later, and some of the patients then die ten to twenty days later, so the time delay is always an important factor that needs to be taken into account.

However, even then, the Italians didn’t declare a quarantine. They didn’t do so on the 29th of February, either, when the total number of infected people rose from 888 to 1128. Those figures implied that in mere days they would be having about 15,000 newly infected people each day. Moreover, they didn’t declare quarantine on the 4th of March, either, when the number of infected people exceeded 3,000, and when the world stock exchanges started to fall again. It had then become clear to most epidemiologists who have been advising global investors that an unexpected and major tragedy was about to unravel in Italy and this was now inevitable. At that point, Italy already had at least 30,000 infected people spreading the infection. The quarantine was declared for Lombardy on the 8th of March. The day before, the number of cases had already risen, and exponentially so, to as many as 5,883.

To appreciate the problem with epidemic spread in the population behind the first line of defense, this is similar to borrowing 1,000 Euros from someone on the 29th of February with an interest rate of 26% each day, meaning an interest rate of 26% on top of that the next day, and so on. Furthermore, there didn’t seem to be enough clear and decisive communication with the public. The news of the quarantine for Lombardy was, in fact, leaked to the media before it was officially announced. This led to a quick ‘’escape’’ of many students to the south of the country, to their homes, carrying the contagion with them. As a result, a day later all of Italy had to be quarantined.

In an already difficult situation, where every new day of delay meant another thousand or more people dying, as we can all notice these days, there were numerous media reports warning that the population may not have taken those measures as seriously as the Chinese when they introduced orders to their population in Wuhan. Any indiscipline under such grave circumstances could have allowed the virus to take yet another step quite easily. With each new step, another 26% of interest was added to everything before that, and then 26% on everything on everything before that again. That is the power of exponential growth, characteristic of free spread of the virus in the population.

Many Italians and then Spaniards, as well as residents of several other wealthy countries in Europe, had their lives cut short by their lack of recognition of the dangers of exponential function during the spread of the epidemic. Delaying quarantine for a week made the epidemic ten times worse than it should have been. Delaying it for two weeks made it a hundred times worse. And after two weeks of it being finally proclaimed, all those who may have not taken the orders seriously enough would have made the epidemic several hundred times worse. This means that, in Italy, and possibly in Spain, too, we are now observing the COVID-19 epidemic that is more than a hundred times worse than it should have been in a country that was much better prepared for the response, such as Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong or the United Arab Emirates.

To appreciate what is happening in Italy, it is enough to think of this sentence alone: at least 100 times fewer people would die each day if quarantine had been declared 2 weeks earlier and had the population stuck to the recommendations. During those fourteen days between 23rd of February and 7th of March, they unnecessarily allowed the virus to spread freely and infect a huge number of people – maybe even up to a million, or perhaps more, it is very difficult to know at this point. This would mean tens of thousands of people in need of intensive care, with about ten times fewer units available nationwide. About half of those who fall seriously ill will not survive without necessary support. At this point, whenever we hear that 1,000 people died in Italy in one day, we should know that the casualties would only add up to 10 had the quarantine been declared just a couple of weeks earlier. I appreciate that it seems implausible that the delay of a political decision like the introduction of quarantine by just two weeks may mean the difference between 100 deaths and 10,000 deaths in the 21st century, but I’m afraid that is unfortunately the reality of the exponential growth of the number of infected during an epidemic.

What does this mean for the public in countries like Croatia, who were confused and in awe of the events in Italy? They should know that they didn’t observe what the COVID-19 epidemic should actually look like in a country where the epidemiological service and its communication with those in power works well, as it does in Singapore, Taiwan or South Korea. In Italy, we have unfortunately noticed the consequence of an omission of epidemiologists and those in power to protect the people from the epidemic. Such a development was not predictable at all. The biggest surprise of this pandemic to date is undoubtedly the lack of response by the Italian authorities to the apparent spread of the pandemic at an exponential rate for two weeks, leading to a very large numbers of infected people in a very short time. But, it is even more surprising that, although the Italian example exposed the lack of capacity of their healthcare system to provide care to all those in need, a similar scenario is now happening in several other European countries in this group, that I initially singled out.

How and why could something like this happen in Italy and then in other countries in the European Union (EU)? I will try to offer at least some hypotheses. First, EU countries have been living in prosperity for decades, focused mainly on their economies. Aside from the economic questions, they haven’t had any challenges that they’ve had to answer to swiftly and decisively, that would measure up to this one. Back in the 1960s, vaccines were introduced against most major infectious diseases, especially childhood ones. Malaria is no longer present in Europe and tuberculosis has been treated similarly for decades. The challenge of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s is now being successfully controlled with antiretroviral drugs. Liver inflammation is treated mainly by clinicians. The impact of influenza is controlled through vaccination while rare zoonoses are resolved with immunoprophylaxis. Even sexually transmitted infectious diseases (STDs) are no longer as significant since the vaccine for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) was licensed.

The last real epidemic that concerned Europe was the Hong Kong flu, which occurred back in 1968 and 1969. The broad field of biomedicine offers such a wide range of exciting career paths to all those students who study it these days, but the epidemiology of infectious diseases is certainly not one of them, at least it has not been in Europe for a very long time. It has probably begun to seem as an archaic medical profession to the large majority of students and young medical doctors. It seemed to belong to the past for the European continent, which made it one of the least attractive things to specialize in. Even the rare epidemiologists who specialized in infectious diseases have begun retraining for chronic non-communicable diseases, due to the aging of Europe’s population, which is particularly the case in Italy and Spain. It seems that at least some EU countries may have fallen victims to their own, decades-long success in the fight against infectious diseases. They faced this unexpected pandemics with few experts that could have had any experience in these events. Asian countries, as well as Canada, have had enough recent experience with SARS and MERS, but some European countries seem to have forgotten how to fight infectious diseases. If it were not for the legacy of the great Croatian epidemiologist and social medicine expert and global public health pioneer Andrija Štampar, and the relatively recent war in Croatia, it is difficult to say whether or not Croatia would be as ready as it has proven to be.

Another thing that likely undermined the Italians response was that no one before Italy, in fact, could have seen how fast COVID-19 was spreading freely among the population. The absolute greatest danger of COVID-19 is its accelerated, exponential spread when it breaks through the first line of defense. However, no-one had the opportunity to study this thoroughly before it reached Italy. Previously, only the Chinese in Wuhan and the Iranians had experienced the free spread of the infection. After five days of monitoring the number of infected, the Chinese had to quarantine Wuhan, and further 15 cities a day later, in order to contain the virus. They did not know how many infected people were outside of their hospitals. For Iran, however, no one knew exactly what was happening there, as that country is significantly isolated internationally due to political reasons. The Koreans, however, had a limited local epidemic but not an uncontrolled free spread – they caught the virus using their first line of defense.

That’s how the Italians ended up becoming the first country in the highly developed world to monitor their epidemic spreading uncontrollably among the population. The only estimate of the rate of spread of the virus to date has been in the scientific work of Qun Li et al. from the 29th of January, published in the New England Journal of Medicine. However, it was difficult for them to subsequently determine R0 parameter on the first 425 patients in Wuhan. Their estimate of the R0 for COVID-19 was 2.2, but with a very wide confidence interval – from 1.4 to 3.9. It’s a bit of tough luck again that they calculated the lower bound of the confidence interval to be 1.4 exactly, because this figure is well known to all epidemiologists. It’s the rate of the spread of seasonal flu in the community. It should come as no surprise that many epidemiologists would guess that, with more data, R0 for COVID-19 would start converging more towards 1.4. Unfortunately, the more recent data suggests that R0 is more likely to lean towards 3.9, implying an incredibly fast spread. Thus, the greatest danger of COVID-19 remained unrecognised in Italy until the 8th of March quarantine measures. At least 100 times fewer people would be dying in Italy these days had they declared a quarantine for Lombardy two weeks earlier than they did.

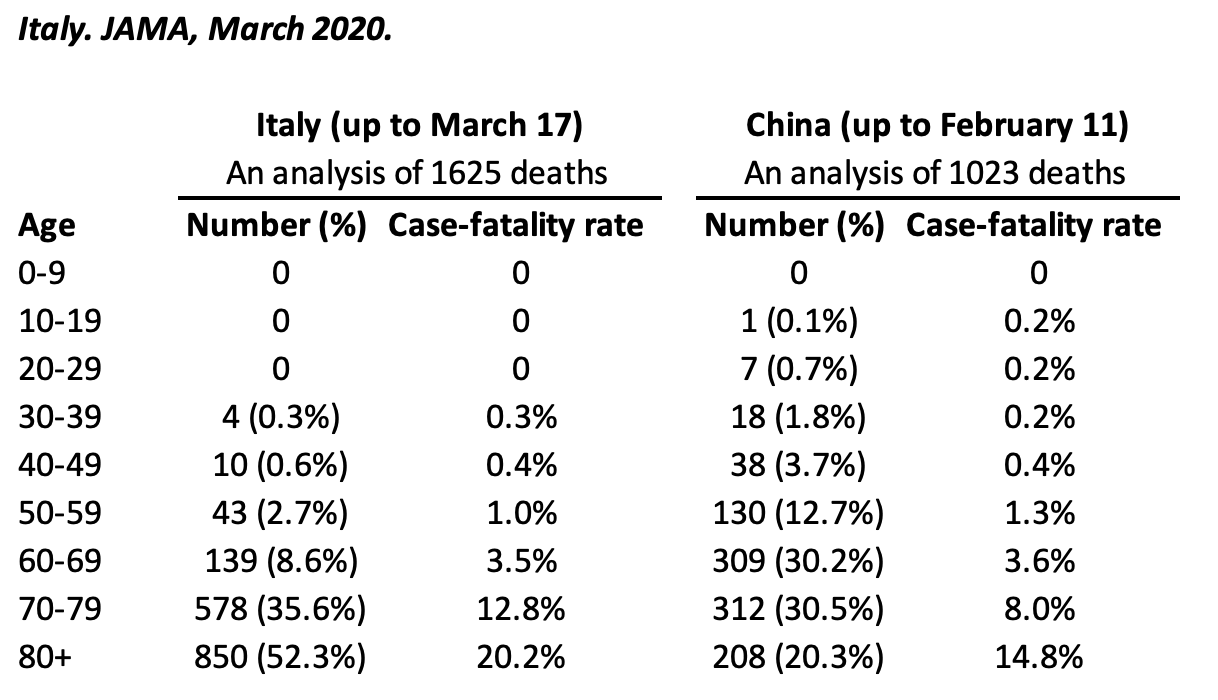

Just a few days ago, the JAMA journal published another extremely useful piece of scholarly work, authored by Odner et al. Their contribution finally provided answers to three great unknowns about COVID-19. Many myths about the situation in Italy have been present in the media since the very outbreak of the epidemic, but thanks to just one simple table, today we can finally dispel them all.

The first is the question that has plagued us all for a long time – how dangerous is COVID-19 for younger age groups? It is clear that the media will tend to single out individual cases of death in younger people, as they are of most public interest. However, it’s interesting that until recently, we didn’t have decent data on this. The first reason was that the Chinese Centre for Disease Control reported all deaths in Chinese epidemic using age group structure that contained a very large age group of “30-79 years”. It only separated children up to 10 years, then adolescents up to 20 years, then 20-29 year-olds, then this huge group, and then those who were 80 years of age or older. That’s why the work of Odner and colleagues is commendable, as they made an effort to divide this large group into 10-year age groups. This finally allowed a comparison between the first 1,023 deaths in Wuhan (up to the 11th of February) with the first 1,625 deaths in Italy (up to the 17th of March). The comparison is shown in the Table 2 below. It gives us some very important insights.

Firstly, in Italy, more than half of the deaths initially were among people who were older than 80 years of age, and a total of 88% of the deaths occurred among the persons over 70 years of age. So, contrary to the impression that individual media reports can easily make, COVID-19 is a very dangerous disease mainly for the old people. Moreover, a study by A. and G. Remuzzi in the March 2020 issue of Lancet showed that, among 827 deaths in Italy, the vast majority of those people were already severely ill with underlying diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and malignancies. This is what epidemiologists expected, because a more severe flu would have had a similar effect if there was no vaccine available. However, I doubt that the general public have the proper insight into this issue from many media reports.

Secondly, it was suggested in the media across Europe that the virus in Italy may have mutated and become much more dangerous. However, Table 2 shows that death rates by the age of 70 are practically the same in China and Italy. Then, although the case fatality rate appears to be about 50% greater in Italy than in China for the age group 70-79, this does not suggest that the virus may have mutated. It is known that in Wuhan, many of the affected with a severe clinical presentation of COVID-19 could rely on the two newly built hospitals and respiratory aids that the military had brought in from other parts of China. They also had medical teams coming in from other provinces. In Italy, however, there were not enough respirators for this age group, and there weren’t enough doctors either, as many of them themselves became infected. For those two reasons I would, in fact, expect even a larger difference between Italy and China than the one we’re seeing, so I would not attribute this observed difference to the impact of the virus itself. And finally, the reported difference in case-fatality rates for the oldest age group should also not be attributed to the virus. It is more likely a consequence of the fact that Italians of Lombardy live, on average, longer than the Chinese of Wuhan. Therefore, there are significantly more people in the oldest age group in Italy, ranging to much higher ages, so the two oldest groups are not really comparable. The average age of the Italians in the age group “80 years or older” is significantly greater than the average age of the oldest Chinese age group. Therefore, the table shows practically equal death rates across all age groups, on sufficiently large samples, meaning that the virus didn’t mutate in Italy from the virus we see from Wuhan, at least not until the 17th of March, 2020.

TABLE TWO: Adapted from: Graziano Onder et al. COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Italy. JAMA, March 2020.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly – this chart has now made it quite clear that COVID-19 does not, in fact, kill people under the age of 50 unless they have some sort of underlying disease, or some unknown “Achilles heel” in their immune system that makes them particularly susceptible to the virus. There are such cases with every infectious disease. They are also present during the flu epidemics, but they are extremely rare. This suddenly gives us another possible quarantine strategy, where children and those under 50 years of age could first emerge if they don’t have any underlying illnesses. Here, after this table, it already seems like we are beginning to have an increasing number of options to get out of quarantines and learn to live with this virus until the vaccine becomes available. However, at least a few more studies need to be carried out to confirm that this age group can be substantially protected, to provide reassurance that the virus is not becoming more dangerous for those younger than 50 years old, too.

There is another strangeness to the situation in Italy that will not be intuitive to the general public. The actual number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 in Italy will not be possible to estimate for several months after the epidemic finally ends. Namely, at present, due to the sole focus on the epidemic, all of the cases of death of very old people who have been diagnosed using a throat swab have been attributed to COVID-19. However, once the epidemic is over, it will be necessary to compare the deaths in individual areas of Italy with the average for the same months in the previous few years. It could be shown that a part of the already ill would have died in the same month or year even without being infected with the new coronavirus, and that COVID-19 accelerated this inevitability by a few weeks or months. In this case, the so-called “reclassification” of causes of death will need to be carried out. The deaths observed during the epidemic in Italy will be attributed to underlying diseases in accordance with expected levels, and only those above expected levels will be attributed to COVID-19. This could ultimately reduce the number of Italians who actually died of coronavirus and otherwise would not have passed away that year.

This article provides an explanation from the epidemiologist’s point of view for everything that has happened so far in Italy, and then followed in Spain and other European countries where COVID-19 has expanded through ski resorts and football games. Simply, a combination of an early relaxation, a possible inexperience in the management of infectious diseases, a systemic lack of expertise in the field, a possible evasion of immigration regulations, and a series of further misfortunes and human omissions have all led to the late withdrawal of Lombardy into quarantine. This allowed for a large number of people to be infected and severe illnesses led to death due to respiratory failure. In 88% of cases, people over 70 years of age died, who, in the vast majority of cases, had underlying illnesses already. But this is an analysis based on the first 1,625 deaths in Italy, and by the time of this writing, there are now more than 10,000 dead. Given the size of the population, this would correspond to 670 deceased in Croatia, which means that in Italy it is more than 100 times worse than it is in our country. This difference may be attributable almost entirely to a two-week quarantine delay.

These days, the people of Italy, Spain and other European countries are suffering large losses because of the problem that the human brain simply cannot intuitively grasp the power of exponential growth, nor that two weeks of delay could make the difference between 100 and 10,000 deaths. Any physics enthusiasts will know that the great Albert Einstein once warned us about this – he said that interest rates, which lead to exponential growth, are “arguably the most powerful force in the universe,” to which no black hole is equal.

This text was written by Igor Rudan and translated by Lauren Simmonds

For rolling information and updates in English on coronavirus in Croatia, as well as other lengthy articles written by Croatian epidemiologist Igor Rudan, follow our dedicated section.