As all Dads will tell you, becoming a father is an incredible experience, a journey I could never have envisaged for myself. There have been many highs, a few frustrations and – especially now with two teenage daughters in the house – never a dull moment. But to have had the opportunity to bring up my kids in Croatia (and largely in Dalmatia) has been an additional privilege.

For raising children in Croatia is a very different – and much more pleasant – experience than I think I would have had back home in the UK.

The first major difference was the so-called Father’s Test, a course fathers are mandated to go on if they want to attend the birth of their child (at least this was the case back in 2006). I was not averse to a little pre-natal classes, but the only problem was that the closest ones available to me on Hvar were in Split. Twice a week, for four weeks, beginning at 20:00, conveniently 30 minutes after the last ferry back to the island.

I decided to take my chances and see if we could negotiate something at the hospital in Rijeka, where we chose to have our kids delivered due to its reputation as the best for childbirth in Croatia. I wasn’t looking to bribe anybody but was hoping that my charm and helpless foreign father routine might do the trick.

To my surprise, it worked, and I was told that for a fee of 300 kuna, I would be allowed to attend the birth. To my greater surprise, I learned that this was not even a bribe. I was given an ‘uplatnica’ pay slip to fill in and pay. But only at the moment that I was informed that my wife had gone into labour. With a receipt of payment in my hand, I hurried to the delivery room and knocked on the door. A doctor interrupted whatever he was doing to let me in, exchanging my receipt for some medical clothing. I was in.

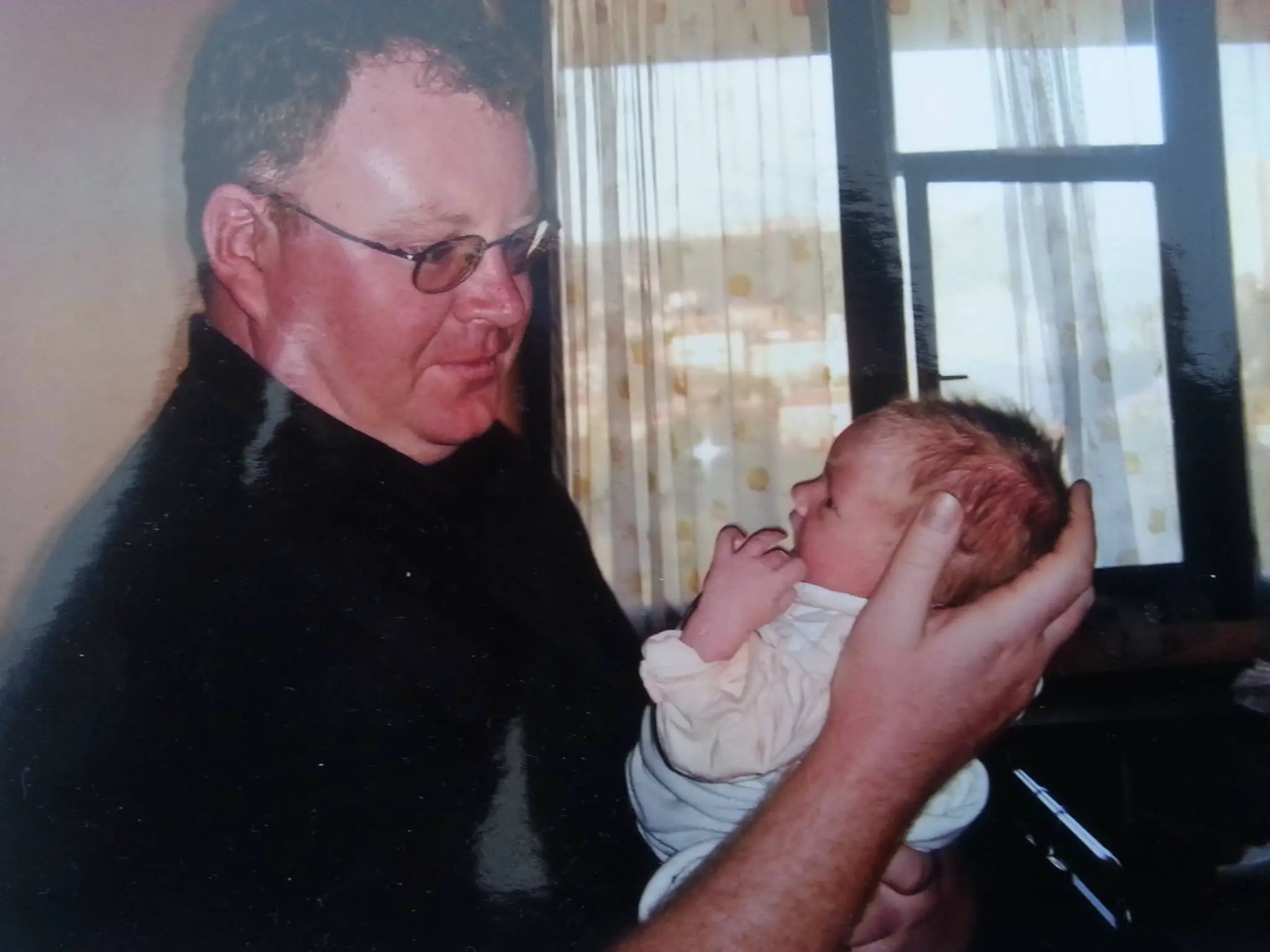

There is something utterly euphoric about witnessing the birth of your child, and I beamed with pride at my wife and newly-arrived (and slightly purple) child. But my contact was short-lived. It was 01:05 on a Monday morning and within 3 minutes of the birth, I was told to go home and come back tomorrow. All of that euphoria and I was separated from my new family so quickly. I wanted to call someone but it was so late, I wanted to celebrate with someone but all the bars were shut, until I found a hole by the Rijeka Bus Station, where I sank a few celebratory drinks in the company of the local drunks. It was not an auspicious start to fatherhood.

(The definition of mutual terror)

The journey home a few days later was terrifying. Having given us a couple of tips and a lesson in changing nappies, our new little princess was handed to us with a message of good luck. I think it was at that point we both realised just how life was going to be different. Taking the overnight ferry back to Stari Grad, we booked a cabin and laid our little treasure on the double bed while we watched every breath in fear that it might be her last. We just had to get back to the island, where my legendary mother-in-law, with four amazing children to her name, would come to the rescue with advice and support.

Just how much support, I was about to find out.

On the ferry, we joked about where exactly Nona would be when we arrived by car. Already waiting on the street, on the terrace etc. What we knew for sure is that she would be our saviour, both that day and for years to come. She was, of course, as close as she could possibly be, already on the street. And so we climbed the steps to our top floor apartment – my wife first, then Nona, then me with child in her basket.

We entered the apartment that cold October morning, but Nona had thoughtfully pre-heated the bedroom. In walked my wife, to be followed by Nona. My mother-in-law then turned around just as I was about to enter the bedroom, took the child and said:

“Bravo, Son. Your job is done. We will take it from here.”

And so the door shut, leaving me a little lost for words and things to do.

I don’t think it was intended in a bad way, or to exclude me from getting involved if I wanted to. I think it was more the way things are done in Dalmatian society. My mother-in-law was (is) amazing in all the help she gave, and I learned that Dalmatian guys tend not to get too involved in things at a very early age. I wanted to be different and was happy to do the nappy changes, taking the screaming monster in the night and being the assistant at bath time. After about six weeks, I had obviously done well enough to be entrusted to take the child out alone.

I had a property viewing on the main square with some American clients, and I put on one of those wraparounds which allowed me to slot the sleeping child in front of my chest. And off we walked together, just the two of us, for the property viewing. The Americans were waiting and cooing over the baby, and then the local owner came, started at me, and asked what was going on. I introduced my daughter.

“Congratulations, but where is the mother?”

“At home, having a well-earned break.”

“Yes, but the child should be with its mother. We just don’t do it this way in Dalmatia.” He was clearly a little distraught over seeing a father alone with a six-week old.

I got into the habit of taking my daughter out for a daily cold one at my local cafe on the square. I had all the kit with me – nappies, wipes, spare clothes, towels, the feeding bottle and formula (once we moved on to the bottle). I trained the owner to bring the water at just the right temperature, and together with my beer, and we made quite the father and daughter team. Although I did notice that she feel asleep a lot as I told my stories, a trend which continues to this day…

I thought nothing of doing nappy changes on one of the empty cafe tables – we are all friends here – and life got into a jolly routine. I enjoyed our little outings together, as well as the compliments from some of the locals about what a good dad I was. Female locals, it turned out, and I learned I had a new nickname on the square – Najtata, or Best Dad. I wasn’t too popular with the male counterparts, however. According to one female friend, I was letting the side down with all this nappy changing – the guys round here didn’t do that kind of thing, and I was making them look bad.

(Hvar’s mightiest river, the Slatina, which runs under Jelsa’s main square. If your child has not fallen in over the years, you are not parenting correctly)

Life continued in that warm, safe Dalmatian way. It was easy to forget just what a paradise I lived in, a loving and totally safe environment for kids to grow up in. Love and devotion at home, and plenty of attention, and a little exploring on our daily excursions downtown. The first steps were taken walking from one cafe to another, all the way across the square. And once the walking came, suddenly life was a little more stressful. Especially as right next to the cafe was an open stream, which local cafes did not want to block access to as they used the water for their own purposes. It was considered a right of passage for a Jelsa child to fall in at some point, and both mine did under my watch.

I was at the other side of a packed cafe the day one of my daughters fell in. She had been talking to friends of mine and suddenly she put a couple of steps forward and in she fell. There was no real danger as there were bars to stop her sailing away into the ocean, but it was obviously not ideal. I raced to her aid and was there just after my friend. I took her through the side door of the cafe, stipped and dried her, then wrapped her in a sarong and presented her to the audience on the square about 30 seconds later, to rapturous applause.

“Now what are you going to tell her mother and grandmother when you get home?”

Sitting on the square with a cold one made you really appreciate the magic of growing up in Dalmatia. The innocence and the ease with which kids connected, even when there was often no common language.

The sense of community, spanning generations, with every child under the watchful eye of all and none at the same time. Mothers free to enjoy their coffee with friends, safe in the knowledge that someone in the community would alert them if there was a problem. Many was the time that a child fell and was in tears and had been fixed up before Mum got to the scene. I loved watching that sense of community in action. And when you also happened to have a cafe where the owners treated your kids like their own, then life was perfect indeed (top tip – Cafe Splendid on the Jelsa square).

Life was not all about what happened on the main square, of course. Coming from a very materialistic society, I found life in Dalmatia to be far superior in terms of teaching kids the value of things. The lack of commercialism was SO refreshing. When I first came to Jelsa, the first sign of Christmas was the tree going up in the main square on December 15. Christmas Day was a big family meal with 1-2 presents each, and then a nice walk in the December sun. Wonderful.

I learned to swim at the ripe old age of 29 when I took an adult swimming class (rather unreassuringly, 7 of those on the course had been on it before), and nothing has given me more pleasure than seeing the kids learning to swim from the age of two. With the Adriatic as their private swimming pool, long days at the beach and the chance to improve their swimming skills became the norm, and two young dolphins where born.

So too with their affinity with the land, something I never had with my bland tomatoes growing in Manchester supermarkets. Watching them helping their grandfather watering the vegetables in the garden, taking part in the olive harvest, helping to clean blitva with Nona, simple things that give them that closeness to Nature that I never had.

And picking a lemon off the tree in the garden for Dad’s evening gin and tonic, obviously.

Nature, safety, love, community and a non-material start to life. Just some of the many reasons why I would highly recommend Dalmatia as a great place to start a family life. And with the rise in remote work, an option for more and more young families these days.

One of the things I was apprehensive about having children was the logistics of kindergarten and schooling. Friends in the UK would describe their daily routines, managing the kindergarten drop and collection with work and other commitments. And when they started talking about the price of kindergartens, it was a little terrifying.

And then there was Dalmatia.

Kindergarten, for a nominal monthly fee, starts from the age of 3 until school at the age of 7. It was a short walk down the steps to the waterfront – the kindergarten was in view from our terrace. And it was not long before the kids felt confident enough to do the walk themselves, waving at the terrace at regular intervals. A 20-metre stroll from my late morning beverage on the square to collect them and then back to the square for an hour before lunch, allowing them to play with their friends or chat to mine. Perfect.

That was an additional benefit of Dalmatian society for me. Kids were included a lot more in things in the community, and having confidence to talk to adults became second nature.

School was very similar, a little further to walk, but a walk that kids did solo from all over the town. Safe.

Dalmatia really is the very best place in the world to bring up children in the first part of their lives, and I am so thankful (especially to my wife and parents-in-law) that I had the opportunity.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning – Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email paul@total-croatia-news.com Subject 20 Years Book