Did you know that women accused of witchcraft in Zagreb weren’t tried by Church superiors, but in civil court? A look at the darker side of Croatia’s history on January 26, 2018

The best known case of witch trials in all of history is the one of Salem: around 150 people were accused of witchcraft between February 1692 and May 1693, only nineteen of them receiving a death sentence. Three centuries prior to the Salem trials, the authorities in Zagreb sentenced the first two Croatian ‘witches’ to death.

While most of us associate any mention of witch trials with inquisition conducted by the Roman Catholic Church, people accused of witchcraft in Zagreb were actually tried in civil court. The Croatian capital saw its first official case of alleged witchcraft as early as in 1360; the unfortunate Alica and Margareta opened the gate to the nauseating practice of torturing and executing women condemned solely on the basis of hearsay.

If a certain neighbour or any other citizen accused a woman of doing them some sort of harm, a trial would swiftly follow, with the accused ending up tortured, sentenced to death and burnt at the stake in most cases. Here’s what the process used to look like, according to historian Denivel Vukelić:

Any person standing trial for witchcraft (regardless of sex, but the majority of the accused were women) was first subjected to experiments. In the early medieval times, they were looking at a chance for absolution if they passed a simple test based on divine intervention or if an influential member of the community vouched for their innocence. A certain local legend says an accused woman from Zagreb was exonerated because the executioner fell in love with her and asked for her hand in marriage.

Later on, the experiments became more brutal or carried out in such a way that would eliminate any chance of acquittal right from the start – they would only add more condemning evidence to the file of the accused. A couple of examples:

The weighing test: a witch must be lightweight to be able to fly, therefore, having a slender build led to a guilty verdict

The crying test: unable to produce a display of emotion such as crying on command? Definitely a witch

The Lord’s Prayer test: if someone could recite the prayer 6-7 times quickly and without making any mistakes, they were a witch

The nose test: the torturer would hit a woman on the nose with a wooden bat, using the colour of their blood to establish whether they were a witch

The cold water test: the accused would be tied up and thrown into a river; if they floated on the surface, they were guilty, if they sank to the bottom, they were innocent

The devil’s mark test: the accused was stripped down in court and examined for birthmarks, believed to be a mark of the devil

Once when a devil’s mark was located on the accused person’s skin, they would be given a chance to confess to their crimes. If they refused to do so, they were subjected to excruciating torture, sometimes spanning for 20 hours or more. Women were forced to disclose names of other witches, their supposed partners in crime; most of them would comply just to put an end to their misery, and the newly surfaced ‘allegations’ would lead to further convictions.

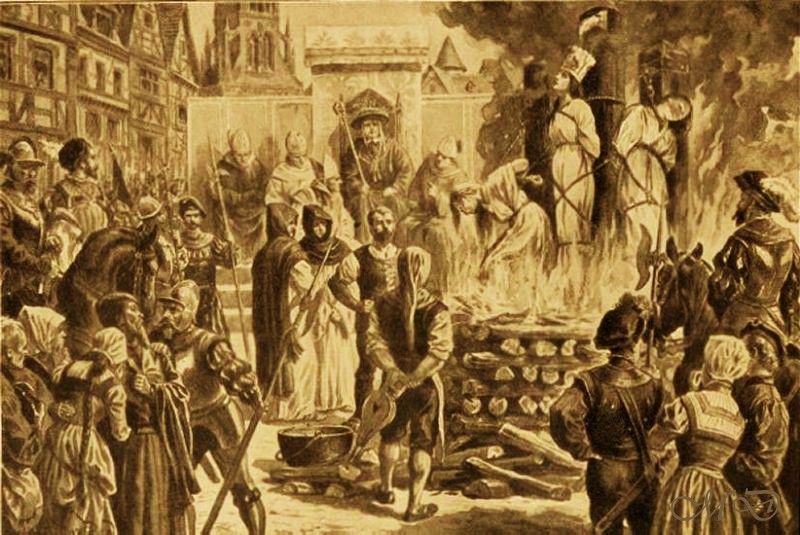

One of the places in Zagreb to serve as a designated execution spot used to be located at the crossing of Streljačka Street and Tuškanac; locals called the infamous spot Zvedišće. Women accused of witchcraft were taken to Zvedišće via Mesnička street, transported on carriages in cases when their legs were forcefully broken during torture. They were followed by the local judge, the public executioner and several guards.

A large crowd would gather at Zvedišće to attend the execution; the judge would read the list of crimes the woman was accused of, then announce the verdict and snap a wooden stick in two over the woman’s body, turning her over to the executioner and his assistants. The woman would be tied to a post, wooden logs laid at her feet. In cases when the verdict didn’t call for the accused to be burnt alive, the executioner would first behead them, then proceed to set the decapitated body on fire.

In the wider Zagreb area, 326 women were accused of witchcraft while the practice was in effect, 106 of them standing trial and getting burnt at the stake. It’s hard to tell how long the hysteria would have dragged on if it weren’t for the empress Maria Theresa, who passed an act in 1756 ordering that all evidence of witchcraft must be handed over to her to make the final decision. A woman named Magdalena Logomer was taken to Vienna, where the empress considered her case and set her free; the court banned the practice of witch trials soon thereafter.

It often took as little as socialising with other women unsupervised for someone to get accused of witchcraft. Other suspicious conditions included being poor, having a fallout with an acquaintance, displaying signs of stubborn behaviour, being young enough or old enough, or simply… being a woman. Go figure.

Sources: Libela, Zagreb.info, Zagrebancija