I normally like to start a new year with a positive, and there are certainly lots of positives in Croatia. As I wrote recently in Improving Croatian Tourism: 8 Key TCN Areas of Focus for 2022, TCN will be focusing on several initiatives this year, several of which I look forward to discussing with Minister of Tourism, Nikolina Brnjac, at our meeting next week. And walking around Zagreb last night was certainly a happy and festive experience, as people put the troubled year of 2021 behind them and hope for a brighter 2022.

But I could just not get the images and conversations of those poor people I saw and talked to in Majske Poljane and Petrinja on the first anniversary of the terrible earthquakes that wreaked so much damage. You can read more in Petrinja Earthquake 1 Year On: Politics, Pain, Problems, But Progress? New Year celebrations in those temporary containers and forgotten, unrenovated houses were probably a lot more muted.

I know that Croatia is very bureaucratic, but is it really so hard to cut through the red tape for a national emergency, such as this? This in a country where the digital nomad permit went from being announced by the Prime Minister in August to becoming law less than 5 months later.

And then someone sent me this article by Boris Dezulovic, which was published last September. Among several issues, Dezulovic looks at the emergency response and complete renovation after the Makarska earthquake in 1962. Some 12,000 homes badly damaged or destroyed. Makarska completely rebuilt 17 months later. And there was not a little irony in the fact that the current Prime Minister (who was born 8 years after the Makarska earthquake) went to school there – his mother probably experienced the quake and aftermath and rebuild.

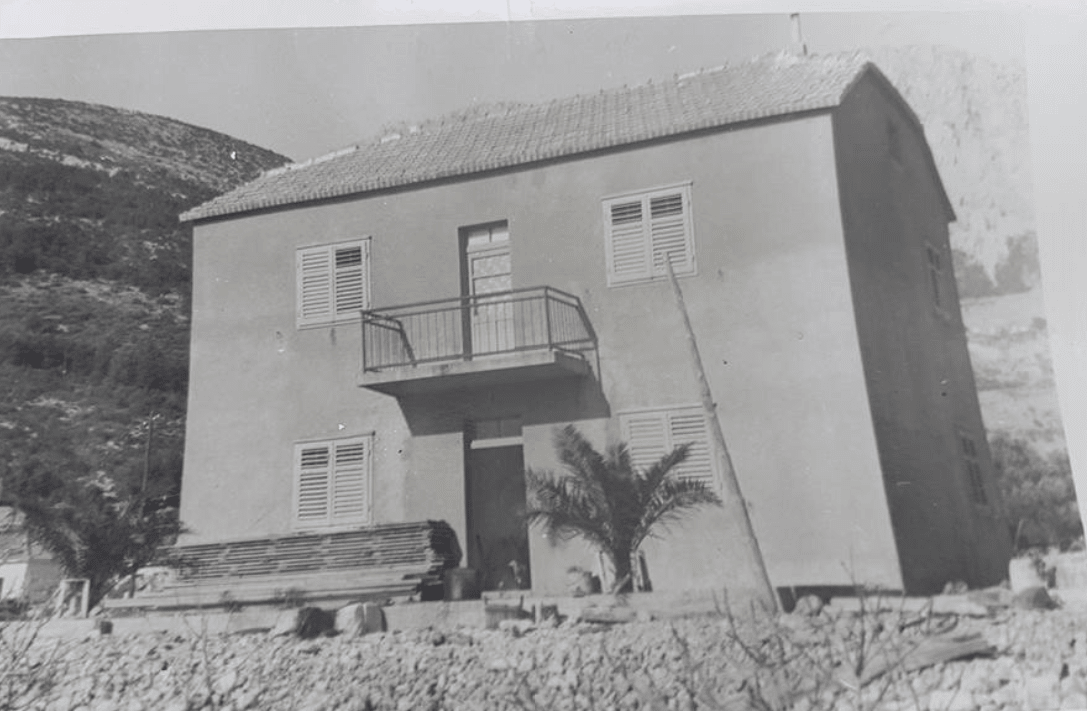

(8-year-old Ivo returned to a renovated home in Zaostrog in May, 1962)

Thanks to Lauren Simmonds for the translation of the article, which is one of the best things I read last year. And at the end, an interview I did a couple of years ago with a friend in nearby Zaostrog, who described the Makarska earthquake and emergency response through the eyes of an 8-year-old who experienced it. An 8-Year-Old’s Memory of the Dalmatian Earthquake of 1962.

****

Asked when the first house will be renovated following the Zagreb earthquake of March 2020, the prime minister replied, quoting: “It will happen when it’s ready. It will be resolved.” Almost a year and a half since the Zagreb earthquake. Five hundred and twenty days. Five hundred. And. Twenty. Days. “Nowhere in the world do things move so quickly when it comes to such damage.” Nowhere? Really?

On Sunday, March the 22nd, 2020, shortly after 06:00 in the morning, Zagreb was hit by a strong earthquake with a magnitude of 5.5 on the Richter scale. One person died in the devastating natural disaster, and about twelve thousand buildings were damaged: red stickers, as unusable and intended for demolition, and yellow, as temporarily unusable, were received by a total of nineteen hundred buildings.

On the sixth day after the quake, Prime Minister Andrej Plenković toured the damaged city. Asked by reporters how, given the lack of builders, he would solve the problem of urgent reconstruction and demolition of damaged houses, Prime Minister Plenković replied that, and I quote, “the Ministry of Construction will solve it, they will prepare a law on reconstruction.”

They didn’t rush when it came to passing that law because – as Prime Minister Plenković explained in Parliament – “such a long-term law cannot and must not be passed hastily”. And it it most definitely hasn’t been: the Law on the Reconstruction of the City of Zagreb was passed by the Parliament almost half a year later. In November – seven and a half months after the earthquake – the Fund for Reconstruction of the City of Zagreb was established, tasked to, and I quote, “perform professional and other tasks of the preparation, organisation and implementation of the reconstruction of buildings damaged by the earthquake, and monitor the implementation of reconstruction measures.” The Reconstruction Act. The Reconstruction Fund. The preparation, organisation and implementation of said reconstruction. Seven and a half months after the earthquake.

“This is a symbol of the beginning of the renewal of Zagreb!”

Damir Vanđelić, the then director of the Reconstruction Fund, announced the above on TV, referencing Ruža Sever’s house in Gornja Dubrava, the first badly damaged building to be demolished in this utterly magnificent renovation project. The owner of the house could not share the same enthusiasm: her house, “a symbol of the beginning of the reconstruction of Zagreb”, was demolished on June the 10th, 2021 – a whole year and three months after the earthquake! – and this poor woman actually died in the meantime.

Until the conclusion of this text, the Ministry of Construction had received about a thousand and a half requests for the removal of severely damaged buildings: of these one and a half thousand requests, the Ministry approved as many as twenty-one. How many have been demolished to date, you might add? Well, if we add in Ruža’s house in Dubrava, that figure is exactly three in total. Three demolished houses. Of a thousand and a half. Three. It’s much easier to add up the renovated ones: out of twelve thousand damaged buildings, the Ministry approved the renovation of three hundred and sixty of them. A total of zero have been renovated to this date. Or, if it’s easier for you, none. Not a single one. Seventeen months since the earthquake.

Knowing that out of as much as five billion and one hundred million kuna from the European Solidarity Fund, Croatia has so far spent only one and a half million in eight months, it is no longer a question of why only one and a half million, but the question of what those funds have even gone to. The President of the Zagreb Assembly, Joško Klisović, therefore announced the other day that a proposal would be urgently taken to temporarily take care of people still being affected by the earthquake in city apartments. A temporary measure. By urgent procedure. Last Wednesday. Seventeen months after the fact.

Finally, aware of minor difficulties in the reconstruction process, Prime Minister Plenković announced an amendment to the Law on the Reconstruction of the City of Zagreb. True, they did need to wait a little while, because Parliament was on a summer break, but “such a long-term law” you know, “cannot and must not be passed quickly” anyway.

“We will correct it all and the matter will accelerate,” Plenković explained briefly, and when asked by a journalist if it all might be a little too late, he replied, quoting: “Well, it will be resolved. Once we look into it, the dynamics of reconstruction will start going. Nowhere in the world do things move so quickly when it comes to such damage.” Asked when the first house will be renovated, he replied, quoting: “It will happen when it’s ready.”

It will happen when it’s ready. It will be resolved. Almost a year and a half. Five hundred and twenty days. Five hundred. And. Twenty. Days. “Nowhere in the world do things move so quickly when it comes to such damage.” Nowhere? Really?

On Sunday, January the 7th, 1962, Makarska was hit by a strong earthquake measuring 5.9 on the Richter scale. Four days later, on January the 11th, shortly after 06:00 in the morning, it was topped off by another, catastrophic earthquake of magnitude 6.1 on the Richter scale. In those devastating earthquakes, thousands of tonnes of boulders from Biokovo became loose and fell, ending the lives of two people, about three hundred houses were razed to the ground, and another five hundred and fifty were about to join them: a total of twelve thousand houses were damaged, with almost three thousand beyond repair, just like in Zagreb sixty years later.

Less than an hour and a half after the earthquake, the municipal headquarters decided to evacuate Makarska, and twenty military and Jadrolinija ships – the Adriatic Highway was not yet there – were transporting people to the safety of Split all day. By the end of the day, a thousand and a half tents had arrived by Istranka boat, and two large camps were set up outside the city and four supply centres were organised: by that very evening, only two hundred people remained in the entire city. A total of nineteen thousand people were evacuated from the entire district, and six thousand from Makarska itself, placed in Split, Zagreb and other cities, where children from the affected families were immediately included in school classes so as to not miss out on their education.

On the sixth day, President Josip Broz Tito visited Makarska and other damaged places. When asked by local government representatives how, given the lack of builders, they’d solve the problem of the urgent renovation and demolition of the damaged houses, President Tito replied that, and I quote, “young people and all able-bodied men should be returned immediately to help rebuild.”

Ten days later, the County Board organised the first working groups and brigades, and formed the District Headquarters, and the Committee for Reconstruction and Assistance to Earthquake Victims was established, headed by Ivan Gac. The Urbanism Council of the Makarska National Committee then accepted the proposal of geological experts on the location of hotel pavilions for the temporary accommodation of earthquake victims, which would then be intended for tourism: in Makarska and Tucepi, six hundred beds were set up, and in Podgora, Igrane and Zivogosce, four hundred also appeared. The Government of the People’s Republic of Croatia, led by Jakov Blažević, then made an urgent decision to grant favourable long-term loans to help the economy of the Makarska Riviera.

And all that by the end of the month. Twenty days since the earthquake.

By July 1962, about four billion dinars of aid had been collected from the budgets of the Federation and the People’s Republic of Croatia, and from companies and individuals, and another billion and one hundred million dinars had been reserved for the local economy in the affected area. Considering that the old settlements near Biokovo had suffered the most, a decision was made not to rebuild those old villages, but to instead move the population down, so they’d be along the coast. People received favourable loans, municipalities provided land, building permits and projects without all of the classic, toilsome bureaucratic formalities and taxes, and local cooperatives provided construction loans. By the summer of 1962, about one hundred and eighty building permits had been issued in Podgora alone, between the sea and the newly laid Adriatic Highway.

Only six months after the earthquake had struck – it was announced that more than seven hundred apartments had already been renovated in the Makarska district, about as many were still in the process of renovation, five hundred new apartments were under construction, and another thousand were being prepared. Seven hundred renovated apartments. So much more were also in the process of renewal. Five hundred were under construction. Preparations were underway for another thousand. Six months after the earthquake. Six months.

Finally, after seventeen months, on June the 8th, 1963 – the five hundred and twentieth day since the earthquake! – in Slobodna Dalmacija, a short news item was published that “there are no more traces of last year’s earthquake on the coast in Makarska”: “The entire pavement spanning two hundred and fifty metres has been renovated and covered with brand new white stone slabs.”

It was, as one would say, “the symbol of the end of the reconstruction of Makarska”. Five hundred and twenty days. Seventeen months. In Makarska. Before modern mechanisation, before the Internet, before the highway, before tourism. Almost sixty years ago.

There is also someone who remembers it particularly well, even though he was born eight years after the earthquake struck. Namely, his mother is from Makarska, where he himself lived as a boy, and his grandfather Marin and grandmother Mila from Podgora often told him about that terrible day when Biokovo collapsed. Just like those children from back in 1962, he went from Makarska to primary school in Zagreb, and later made a nice political career there and even became the prime minister. When he himself experienced a terrible earthquake in Zagreb many years later, the newspapers were spilling over with his words:

“Nowhere in the world,” he said confidently at the time, “do things move so quickly when it comes to such damage.”

The original artice appeared in Croatian in Portal Novosti on September 3, 2021.

Read more An 8-Year-Old’s Memory of the Dalmatian Earthquake of 1962.