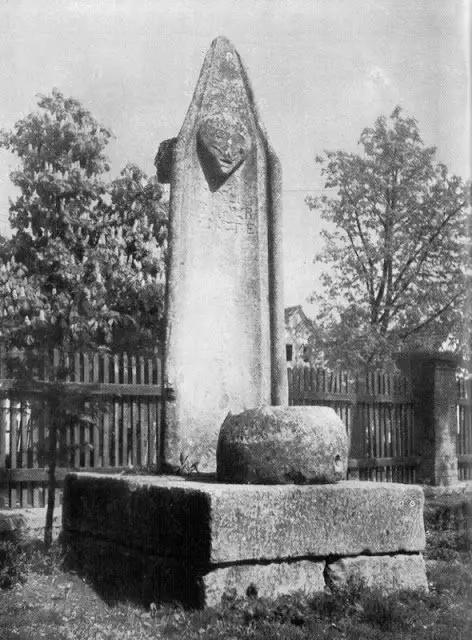

In a village called Salež, not far from Buzet town in Istria, stands a solemn monolith. A human figure carved in stone, weathered and overgrown with moss.

It’s not an old deity you’re looking at, but a pillar of shame, a once popular tool for punishment by public humiliation.

Transgressors of all kinds were tied or chained to stone pillars, typically set up on town squares or other public places of gathering, and left to the mercy of the mob. The more severe the offence, the longer the convicts had to endure the misery, with more serious crimes often warranting corporal punishment on top of the humiliating public exposure.

Pillar of shame in Salež, Istria / Buzet Tourist Board Facebook

Pillar of shame in Salež, Istria / Buzet Tourist Board Facebook

Pillars of shame existed all over Europe, Croatia being no exception. Public shaming was judicially sanctioned until emperor Joseph II banned it as a method of criminal punishment in the 18th century.

The practice lived on in other ways; most recently, it moved to the virtual space where it assumed a more insidious form. Social media only seems to instigate the mob mentality, and gone are the days of public punishment lasting an hour or two – your past transgressions are forever saved for anyone to find. The internet never forgets, and the old stone pillars and chains almost seem benign in comparison.

In Croatia, several pillars of shame survive to this day. The anonymous figure in Salež is arguably the most unique of the lot – and the most unsettling – as it’s the only one that has a human form.

Among the locals, the pillar is known as Berlin, getting its name after berlina, a type of four-seat carriage that once operated on the route Berlin – Paris and was used for transportation and public shaming of convicts. Berlin the pillar is made of white stone that isn’t naturally found in the area. The figure wears a cap, and is resting its left hand on his chest, on a spot once used to clip the chains with which the convicts were tied.

There’s an inscription in Latin on the front of the figure, barely visible, translating to justice to this poor province.

A local named Mate Grižančić recalls that the village elders used to speak of the pillar being brought to Salež on a carriage adorned in flowers, pulled by six of their strongest oxen. A parade of eighteen girls dressed in white followed the carriage as it rolled into town.

Church of St. Servulus in Buje / istra.hr

Church of St. Servulus in Buje / istra.hr

Another pillar of shame in Istria is found in Buje. The town is truly the best of both worlds where Istria is considered: it spans over two inland hills, giving off the classic Istrian-hilltop-town vibes, with the sea glimmering on the horizon as the coast is only 10 kilometres away.

Pillar of shame, church of St. Servulus in Buje / Creative Commons

Pillar of shame, church of St. Servulus in Buje / Creative Commons

At the highest point in town, in front of the imposing Baroque church of St. Servulus, you’ll find a pillar that was reportedly used for public humiliation in the 17th century, and later as a flag pole. Spot the Venetian lion on the pillar and elsewhere in town, remnants of the long period of Venetian rule.

An honorary mention goes to Sveti Lovreč, one of the best preserved fortified medieval settlements in Istria which gets its name from the small church of St. Lawrence.

Perched in the centre of the main square is a pillar of shame that’s only partially preserved, standing on a pedestal.

Sveti Lovreč, pillar of shame in the bottom right corner / Image by Central Istria Tourist Board

Sveti Lovreč, pillar of shame in the bottom right corner / Image by Central Istria Tourist Board

Public shaming sure seems to have been a popular method of punishment in Istria – what about the rest of Croatia?

Quite a unique landmark is found in Vinica near Varaždin. It’s locally known as pranger, named after the German term for a pillar of shame. Originally located at the Vinica fortress, the pranger was moved several times and is now installed at the Matija Gubec Square.

The three-sided pillar is slightly reminiscent of an obelisk; each side is crowned with a man’s head, carved in stone. The three faces all have different features, but share a chiselled moustache as a common trait.

Pillar of shame in Vinica / Zagreb Nekada Facebook

Pillar of shame in Vinica / Zagreb Nekada Facebook

Next to the central figure, the year 1643 is engraved, followed by a Latin inscription:

IVSTAM MENSVR(AM) TENETE

Measure honestly, it warns. Together with the round stone vessel installed on the pedestal, the inscription points to the fact that the Vinica pillar doubled as a measuring tool. Grain and similar produce were measured with the help of stone pots since medieval times; the merchants who were caught trying to cheat their customers ended up tied to the pillar and were given a thorough thrashing – verbal or otherwise.

On the coast, a famous specimen of its kind is found in Zadar, standing at the northwest side of the Roman forum.

Given its former purpose, the slender column looks much more intimidating than its Istrian counterparts. Fourteen metres tall and ancient Roman in origin, the column was repurposed into a pillar of shame in the Middle Ages.

Roman forum in Zadar, pillar of shame on the left / Creative Commons

Roman forum in Zadar, pillar of shame on the left / Creative Commons

Nowadays one of the most popular spots in town, the location surely used to instil unease in the local population back in the day. Offenders of all kinds were chained to the pillar and left exposed in public for several hours on average.

Women who were caught emptying their night pots through the window or throwing any other kind of garbage into the street got an hour on the pillar. A sign was hung around their neck that read šporkulja – a title that doesn’t translate well, but indicates the woman was messy or dirty.

Pillar of shame in Zadar / Marco Verch, Creative Commons

Pillar of shame in Zadar / Marco Verch, Creative Commons

Other offenders were given a sign as well, listing all their transgressions; theft and solicitation were the most common offences. The gathered masses were happy to hurl insults at them, as well as a wide range of objects. If a person was accused of theft, they’d get a lashing on top of being harassed by the public.

Offenders were often forced to pay a fine for the privilege of pillar use after the entire ordeal – a whole new level of adding insult to injury.

Further south, in the town of Omiš famed for its pirates, a pillar of shame stands on a square near the river Cetina. The final item on our list, the elegant column bears the insignia of the Venetian general, and it’s believed it dates to the 17th century.