January the 15th, 2024 – Have you ever heard of the contraband trails of Učka mountain? Nikolina Demark takes us to the mountain’s foothills and to the village of Šušnjevica. It’s not a destination to make headlines or get a mention on a must-see list. Yet, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better place to visit if you happen to like going off the beaten path…

Šušnjevica packs so much to discover, including a history of smuggling, stories of survival, and a dying language. The many facets of this incredible little place are presented in an interpretation centre named Vlaški puti (Vlach paths), introducing visitors to the social history and cultural heritage of the area.

Clandestine activities always seem to draw the most attention, so it only makes sense to start there: the unassuming village is located in the area where illicit trade thrived in the early 20th century.

For a bit of historical context, the Italian-ruled Kvarner Province at the time encompassed the wider Rijeka area, including a chunk of Slovenian territory in the north, and all the settlements lining the Opatija riviera in the south.

In 1930, the coastal part of the province was declared a duty-free zone by the Italian government (zona franca). The economic crisis left a mark on these parts as well, development of tourism was stalled, and so the decision to abolish customs was meant to shake things up a bit and give Rijeka and Opatija an edge over other popular destinations in the Northern Adriatic.

Naturally, consumer goods suddenly became much cheaper in the duty-free zone than in the rest of the province, and the local population was nothing if not resourceful. Living conditions were tough at the time, especially in rural areas, and any opportunity to make a living was seen as more than welcome.

And so the people of Šušnjevica and other villages in the area started running contraband, smuggling inexpensive goods out of the duty-free zone. They sold their produce and poultry in seaside towns, and in turn mostly purchased sugar, coffee, textile and petroleum. The illicit goods were transported on foot over Učka mountain and resold for profit in the rest of the region.

It was a dangerous business, both in terms of scaling rugged mountain slopes and avoiding the unforgiving customs officers who monitored the area. It should be mentioned that contraband goods were not smuggled out of greed for profit, but solely to ensure survival in times of scarcity.

If you’re up for a hiking adventure, you can now retrace the steps of smugglers past. Three hiking trails have been established in the territory of Učka Nature Park to introduce visitors to the lively history of contraband in the area. A mobile app was launched, containing detailed information about the hiking routes, along with a list of accommodation providers and restaurants in the area. It’s available to download on GooglePlay and AppStore – look for Kontraband thematic trails.

All three are demanding routes and vary from 6 to 10 kilometres in length, but are well worth the effort – the trails are scenic, feature wonderful views, and you’ll get to see a few historic sites along the way. Among them is the abandoned village Petrebišća, a place of importance in regards to Slavic mythology. Another stop commemorates a young smuggler who tragically died aged 12 when he got struck by lightning on Učka mountain; following his death, every smuggler in passing would lay a stone at the memorial site, which in time grew into a massive pile of stone, the so-called gromača.

The shortest trail (KB1) starts in Šušnjevica, and those who opt to take this route should really use the opportunity to discover more about this fascinating place at the Ecomuseum Vlaški Puti.

Director of the interpretation centre Viviana Brkarić is more than familiar with the subject, having had family members who dealt in the contraband trade. Viviana speaks of her grandmother, born in 1901; times were tough, she had to support her family, and was known to make the trip to the duty-free zone and back 3-4 times a week. She’d occasionally get caught smuggling goods over Učka which landed her in prison, but she didn’t mind as it meant ‘she’d get to rest for a while’.

The prison guards soon realised she knew how to sew, and would have her sew clothes and mend bedding. According to Viviana, grandma didn’t mind as they treated her as a guest and gave her better food than to an average prisoner. Apparently, the guards were quite happy to see it was her every time she was apprehended, and were known to say ‘she’s here, she’ll now mend everything that needs mending’. (Agroklub/Blanka Kufner)

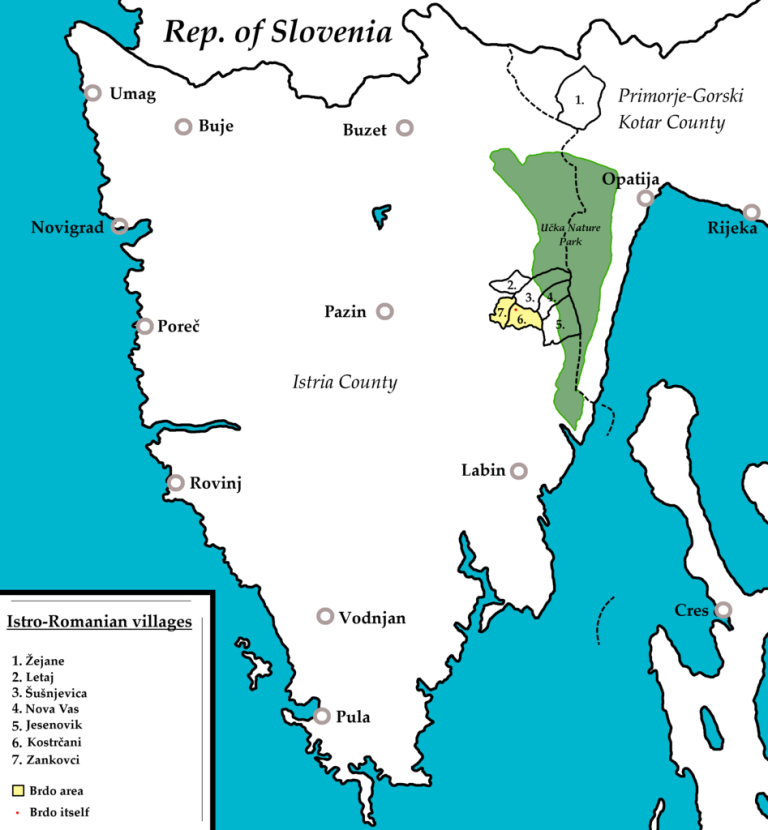

These days, Šušnjevica is home to about 70 people, most of whom are Istro-Romanian in origin and are some of the last living speakers of Vlashki (vlaški), one of the two existing varieties of the Istro-Romanian language. The other variety is called Zheyanski (žejanski) and is spoken in the Žejane area on the northern side of Učka mountain.

Once spoken in a much larger part of northeastern Istria, Istro-Romanian is now listed as ‘severely endangered’ in the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages, and is inscribed in the list of protected intangible cultural heritage of Croatia. In the mid-20th century, the language was reportedly spoken by up to 1500 people, but the numbers dwindled as the harsh living conditions drove people to move to bigger urban areas in the country or emigrate to the US and Australia.

Interestingly, nowadays there are more native speakers of Istro-Romanian living in New York than in Croatia. It’s estimated there’s a community of some 300 people keeping the language alive in the diaspora, whereas the latest count from 2019 put the number of Vlashki speakers in Croatia at about 70.

The language is not passed from generation to generation anymore, and so the youngest people who actively speak Vlashki are about 50 years old.

Preserving this priceless heritage for future generations is one of the goals of the ecomuseum. The interpretation centre is designed to introduce visitors to the local history and traditions, while the media library contains materials in Vlashki and Zheyanski languages, as well as digitised publications about the language and other topics of regional importance.