Like every year, 2021 is no different, and March 8 is marked as International Women’s Day. The day that celebrates women’s emancipation but sadly reminds us that the battle for true equality is still ongoing. Given that massive gatherings still aren’t recommended due to the coronavirus pandemic, the annual Noćni Marš (Night March) in Zagreb will not be held this year as confirmed by the feminist collective Faktiv that regularly organizes the event. On the other hand, this year has seen gruesome stories and confessions of sexual abuse, harassment, and even rape all over the Balkans and Croatia too, as is evident by the posts and public outcry gathered by Nisam tražila (I didn’t ask for it), an initiative that connects women (as well as male victims of sexual violence) and provides a safe space to share their stories anonymously). What do these recent events tell us about gender equality and does Croatia fall behind on gender equality compared to the US or other Western countries?

Dr. Mala Matacin is a born American. If that sounds odd, it’s not just because of the Croatian surname but also because her name is a female gender version of the Croatian noun for „little“ (malo). Her father is from Preko on the island of Ugljan and her grandfather on her mother’s side was from Gromača, a village near Dubrovnik. From September 2019 to March 2020, she was on an academic sabbatical in Croatia where she still has a family and is very enthusiastic about re-visiting post-pandemic. Apart from being on a quest for her family’s roots, she spent her time meeting with academics and students at several universities and learning from activists. One of the highlights of her time here was being able to attend and participate in „Night March“ last International Woman’s Day. When it’s safe to travel, she hopes to bring students to Croatia for a short-term study abroad program.

Matacin has a Ph.D. in Social Psychology with post-doctorate training in Behavioral and Preventive Medicine. She is teaching at the College of Arts and Sciences, the University of Hartford in the state of Connecticut. Her research is focused on women’s health (primarily in the issues of body image and stress), women’s leadership, and the relationship between images and social change. Matacin also has an interest in gender issues and she started and teaches a course „Women, Weight, and Worry” which according to the official Hartford University website is a „popular University honors course“. She also teaches a freshman year course “Beauty, Body Image, and Feminism”. She has designed two new University courses—one focused on systems of oppression and the other focused on photography and activism. Additionally, Dr. Matacin is the founder and faculty advisor for “Women for Change”, a campus organization focused on gender and other equity issues. She has received multiple awards for her work (“Outstanding Teacher Award” in 1999, “Excellence in Service to Students” in 2010 by Sigma Alpha Pi, the National Society for Leadership and Success, “Innovation in Teaching and Learning Award” in 2018, the “Roy E. Larsen Award for Excellence in Teaching and Contributions to University Life” and “Outstanding Faculty Award” in 2019). A 2009 post-graduation survey done by the Career Center named Dr. Matacin one of the three top faculty members in the entire University of Hartford community as a faculty member who had a major/positive impact on students. Just last weekend, during the opening ceremony of the Association for Women in Psychology virtual conference, she received the organization’s mentoring award.

I spoke to her about her experiences from Croatia, legal frame, Sex-ED, and what does she overall think about gender equality in the country compared to the US.

prof. Mala Matacin at Noćni marš (Night March) / private archive

You first came to Croatia in 2020. You participated in the Noćni Marš in 2020 for the International Women’s Day in Zagreb. Can you tell us more about how you came about with the organizers, you even hosted workshops for the participants right?

On March 1, 2019, I attended a workshop organized by Faktiv (a feminist collective) and Le Zbor (the first mixed lesbian-feminist choir/band) to learn the “Patrijarhat Siluje” chant and performance. “Patrijarhat Siluje” (Patriarch Rapes) is a translation of the Chilean protest anthem (“Un Violador en Tu Camino”) about rape culture and victim shaming. We learned the chant and choreographed performance to perform during the march (Noćni Marš). At the workshop, I also met several women who were part of Žene ženama, an organization that provides a safe space for women who are refugees/asylum seekers and call Croatia their home. I’m grateful to this organization for generously including me and marching behind their banner on March 8th (Noćni Marš ). In the United States, I participated in similar chants and dances to protest violence against women and girls. So, being in Zagreb for International Women’s Day was an extraordinary experience for me. Over 7,000 people took to the streets for Noćni Marš starting from Trg žrtava fašizma. The theme was Živio feminizam! Živio 8 Mart (Long live feminism! Long live March 8th!) and I was honored to stand with my Croatian sisters and meet new friends and colleagues at the protest.

What do you think about Croatian gender equality activists? From what you had the chance to see, are they doing a good enough job in advocating solutions to these problems, or is there something they still have to learn from their colleagues in the US or other western countries?

I spent most of my time connecting with scholars doing academic work on issues related to gender and didn’t meet activist groups until March. My unexpected return to the United States that month due to the coronavirus did not leave me with as much time to interact as I wanted to. What I did experience was quite similar to those I’m familiar with—intelligent, good community organizing, active in their efforts to address gender and other social inequities, warm and generous (as evidenced by their willingness to accept me into their midst), and finding creative ways to get their message across. Activism is most commonly associated with public protest and marches, but artists can use their medium (for example, poetry, photography, performance, music) to challenge systemic injustices, and I was able to see and meet several artists in Croatia who were doing that.

Were you informed about gender equality problems in Croatia before coming to the country or was meeting up with activists in Croatia an eye-opener for you? Was there something about them that surprised or shocked you that you didn’t expect to hear?

I was on my academic sabbatical in Croatia from September 2019 – March 2020. In preparation for coming to Croatia, I tried to read as much as I could about the state of affairs for women and the LGBTQ+ community and the country’s efforts to address gender inequalities. For example, I found out about the Ombudswoman’s Office for Gender Equality and was lucky to meet with two representatives in the office in February 2020, I spent the first three months of my time in Croatia in Dubrovnik and the last four months in Zagreb. This is important because I found a difference between these two parts of the country. Dubrovnik is more conservative and it wasn’t until I got to Zagreb that I found people doing activist work. Also, although I am American-born, I am Croatian on both parents’ sides. As such, I’m familiar with the patriarchal Croatian family dynamics; in fact, it’s one of the reasons I’m so interested in gender issues because it’s personal.

It’s such a great question about anything that surprised or shocked me. I probably could write an entire article on the things that were surprising (and I should!), but as for shocking—there is one—the #MeToo movement not gaining traction in Croatia. In the United States, the movement exploded in 2017 and was very much part of the country’s narrative but I found it surprisingly absent in Croatia. Instead, I learned about the #spasime movement which is centered around domestic violence (very much focused on the family unit). Thanks to you, I have also been made aware of „Nisam tražila“ which some are arguing is the Balkans #MeToo movement. What is striking to me is the similarity in the way both #MeToo and „Nisam tražila“ gained „sudden“ attention and visibility—both were popularized by actresses within their respective countries. In this way, there is value to those who can use their privilege to bring attention and visibility to social injustices that grass-roots activists spend most of their lives addressing.

You are born in the US but aware and proud of your Croatian roots. The Croatian diaspora is big and quite well-formed in the US. Are you associated with other Croats in the US and how does the diaspora feel and think (if it even follows) the gender inequality in the country? The liberal stream in Croatia often looks negatively on the diaspora as they see them as conservative, uninformed, or indifferent about the actual problems in Croatia despite having and exercising voting rights on Croatian elections. Do you vote as well?

Unfortunately, I have never lived in a part of the U.S. where there has been a strong, well-connected Croatian community. Much to the dismay of extended family who did grow up within the Croatian diaspora, my siblings and I do not speak Croatian and are overall less immersed in Croatian culture. But, I think this has had its benefits too. As you suggest, my experience with the Croatian diaspora in the United States is more conservative and indifferent to problems in Croatia, particularly as it relates to women. There is a phrase I learned when I was in Croatia—tako je—which seems to be spoken when one has given up on trying to solve an issue or there is simply an acceptance for „what is“. Had I grown up fully absorbed in the Croatian community in the U.S., I might be more accepting of „what is“ when it comes to fighting injustice. Ironically, my being steeped in a deeply Catholic family as a child instilled this sense of fighting for marginalized groups. I went to college at a Jesuit University and the Jesuits are well-known in the Catholic tradition as being socially progressive. I guess you can say that my feminist awakening happened within the context of a Catholic institution that taught me to challenge ideas and commit to social justice.

I absolutely vote here in the U.S. but have no voting rights in Croatia as I’m not a citizen. I was actually in the midst of getting my Croatian citizenship when I had to leave Zagreb last March. I’m still really sad that I could not complete the final steps when I was there.

Noćni marš (Night March) 2020 © Lara Varat

A similar-to-me too-movement came about in Croatia and the Balkan region known as „Nisam tražila“ (I didn’t ask for it) in 2021. Since Serbian actress, Milena Radulović, publicly accused her acting professor Miroslav Mika Alekšić of raping and abusing, similar accusations spawned on the acting academia in Zagreb and other faculties on the University of Zagreb and many more confessions from everyday people (mostly female but also male) experiences with sexual harassment, collecting 40,000 confessions in the first week from all over Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia, and Herzegovina) on the „Nisam tražila“ Facebook page. Are you following this situation and what do you think about it?

Thanks to your question, I’m now definitely following it and trying to read as much as I can. As I noted in the question you asked me earlier about things I was surprised or shocked by, it was about how the #MeToo movement had not really taken off in Croatia as it did in the United States. I’m glad to see that there is visibility and acknowledgment of the sexual violence, abuse, and harassment of women in the Balkans. Sexual violence perpetrated by men in power needs to be seen and stopped.

What do these confessions both in the US and Croatia say about the acting community? What caused so much sexual blackmail in this particular field?

I don’t think that the truths of sexual violence say anything about the acting community—what it does say is that those who have a public platform to acknowledge such abuse create visibility that those who are „ordinary citizens“ do not. People like Milena Radulović from Serbia and Alyssa Milano from the United States only magnify and make public the work of activists and community organizers. I don’t know enough about activists in Serbia, but in the United States, it was activist Tarana Burke who first used the term „me too“ in 2006 and started the movement. #MeToo only went „viral“ in 2017 because of celebrity actions on social media. I feel it’s very important to highlight the often invisible work of such activists. Blackmail only happens because the person in power knows they did something wrong and doesn’t want the public to know about it because it might damage their reputation. Only those with enough influence, power, and money are privileged to use blackmail and one of those sectors is the acting community.

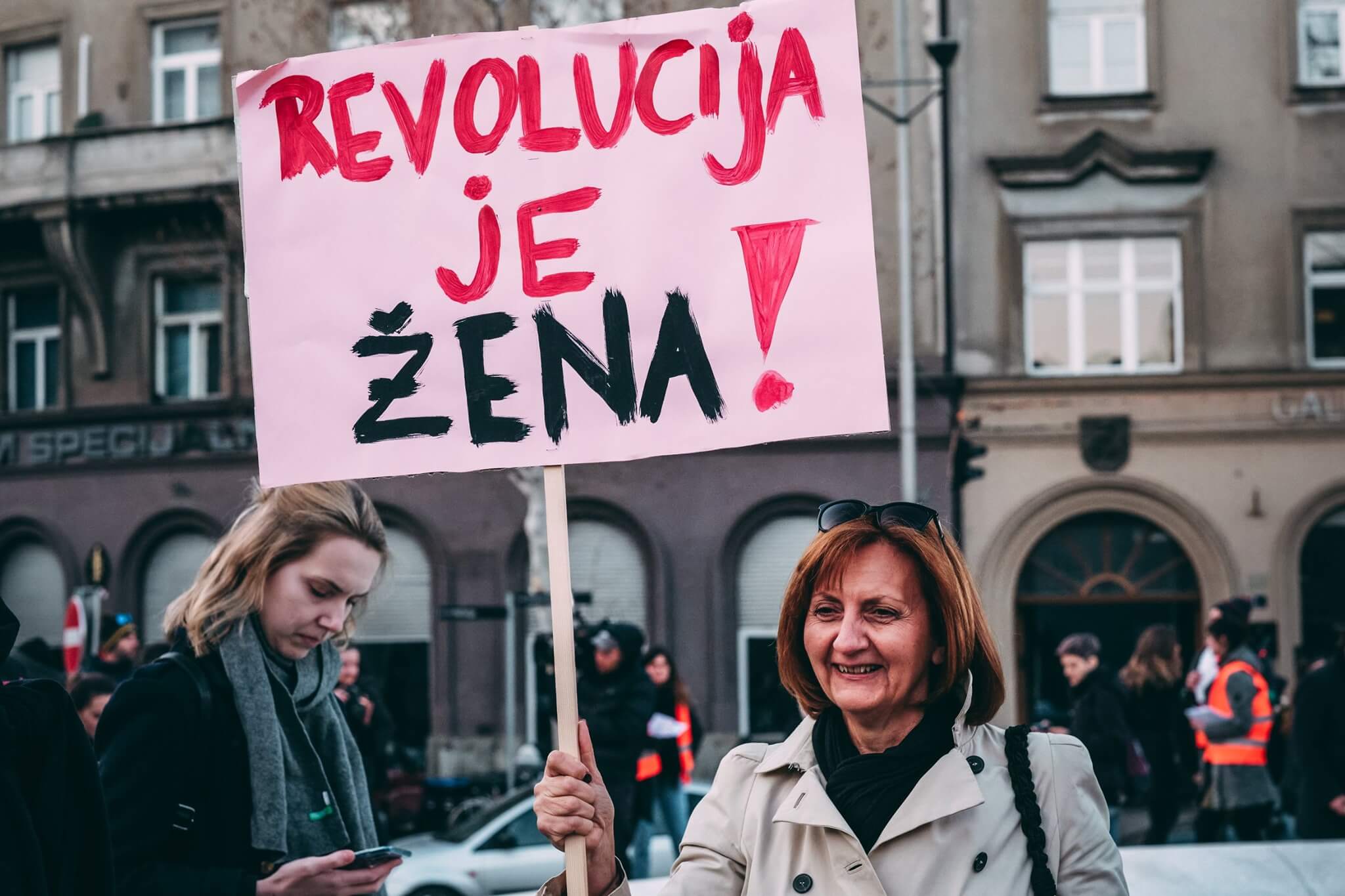

“Revolution is a woman”, Noćni marš (Night March) 2020 © Lara Varat

„Laws are necessary but not sufficient“

Višnja Ljubičić, the Ombudswoman for gender equality demands changes in the law. As current law in Croatia allows legal prosecution up to three months since the event of sexual harassment occurred, Ljubičić asks for the law to increase for up to ten years. The law also states that sexual harassment is investigated only if the victim reports it and not ex officio, like for other sex crimes, which Ljubičić says also needs to change. How would you compare the current law in Croatia and Ljubičić’s proposal to the law in the US? Is it stricter than Croatian and what changes did it go through throughout history?

I’m not a legal scholar and honestly, I find it quite confusing due to legal jargon and federal vs. state law. Federal law states that a person can have 180 days to report sex discrimination (sexual harassment is one type) in companies with more than 15 employees. In small workplaces (under 15 people), workers have no formal legal protection. Only seven states extend the time limit to more than 300 days. Finally, five states do not even have an office that enforces anti-discrimination cases. Others can report the sexual harassment for someone else, but there is no anonymity for the victim as the case must be investigated. Current time limits are similar between the countries. I am not familiar with the details of either country’s laws (to say which is stricter), but what I can tell you is that visibility matters. As outlined in this article in Time magazine, the term „sexual harassment“ was not coined until 1975. But, the case that really made sexual harassment visible in the U.S. was Dr. Anita Hill’s testimony against Supreme Court Nominee Clarence Thomas. As stated in the article: „Though Thomas denied the allegations and was eventually confirmed to the Supreme Court, Hill’s decision had immediate consequences: in its wake, sexual-harassment complaints filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission doubled, and payouts from court settlements increased as well.“ However, it’s important to note that when there is progress, there is also backlash.

Maja Mamula, a psychologist, and coordinator for „Ženska soba“ (Women’s room), a non-profit organization for the prevention of sexual violence, suggests that due to the long period of the judicial process, institutions in which the accused is working should sanction and isolate themselves from the perpetrating suspect before the judges’ ruling. She added that despite the „presumption of innocence until proved otherwise“ this is the minimum institutions should do even before the verdict. How would you comment on this proposition and how do people feel about this in the US as well? In your view, is there any possibility to ensure justice for the victim but also respecting the presumption of innocence? Should courts just be quicker or is there a more in-depth issue at stake?

„Is there a more in-depth issue at stake?“ is what’s important from my perspective. It’s highly problematic that we allow contact between individuals when a person’s life is at stake due to violence. One should not have to request a restraining order (another legal step) to ask that an abuser not come near the victim. Legal protections only deal with laws and not the ethical or systemic inequities built into the system. For example, the legal system benefits those who have money, can access the internet, are English-speaking (in the U.S.), citizens, White, male, cisgender, etc.

“Trans women are women”, Noćni marš (Night March) 2020 © Lara Varat

Mamula also warns that the Council of Europe suggests that for 200,000 residents there should be one center for the prevention of sexual violence, but the Croatian government ignored the proposition to establish three new centres. What is the situation with such centers in the US, are they sufficient enough and if so, do they help society in supporting the victims and encouraging more reports of sexual violence?

The U.S. federal government has an Office on Violence Against Women that is part of the Department of Justice. The office does not provide direct aid or support to citizens but rather administers a grant program „designed to develop the nation’s capacity to reduce domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking by strengthening services to victims and holding offenders accountable“. It’s important to note that this office was created in 1995 after the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was enacted. Congress must reauthorize VAWA every five years and this has been done until 2019 when bipartisan support could not be obtained. Extending protections to vulnerable groups since 1994 has included indigenous populations, transgender individuals, and victims of human trafficking. VAWA does not currently protect girls at risk for female genital mutilation (FGM), immigrant populations, forced child marriage, or honor killings. To the best of my understanding, the lack of this Act not being reauthorized does not remove legal improvements made since 1994, but limits grant opportunities. Federal laws make a difference in reducing violence but there is no doubt the effects vary by state due to local regulations. In addition, there is little federal oversight in evaluating the effectiveness of grants provided to various organizations.

Whether these laws are sufficient is a good question. I do not believe they are. Laws are necessary but not sufficient. Laws do not necessarily address ethical issues or structural barriers that prevent equal access to protection. Justice cannot be accessed in marginalized groups that do not have financial or linguistic resources. They may also fear the legal system or simply have no idea how to access help. Even in trying to respond to your question, I had to do a lot of reading, searching, and understanding my own country’s complicated laws—imagine being poor, an immigrant, or a member of a gender-minority group and trying to cope with the trauma of violence. Laws do nothing to mitigate unequal access.

Even when a woman has access and her case goes to court, her word is subject to victim-blaming—essentially an argument that she is personally responsible for her own victimhood (e.g., rape). Victim blaming is an example of something called the „fundamental attribution error“ (or correspondence bias) which is our tendency to blame individuals rather than the circumstances or situation. There are countless examples of citizens protesting victim-blaming in rape trials globally but it is still a tactic used in court to discredit a victim’s story. Victim-blaming shifts responsibility away from the perpetrator. Activists and scholars say we are asking the wrong questions when it comes to sexual assault. The focus needs to shift from the victim to the abuser. For example, in the case of domestic violence, instead of asking „why does she stay?“, we should be asking „why does he hit her?“ In conjunction with laws to protect victims and hold perpetrators accountable, we absolutely must be addressing such biases and tactics within the legal system.

Another suggestion regarding the prevention of sexual harassment that is seeing bigger and bigger support in Croatia is introducing sex-ed in Croatian schools. This is something that ranges widely in the US as well. According to the Planned Parenthood website, there is a huge public support for Sex-Ed but „currently, 24 states and the District of Columbia mandate sex education and 34 states mandate HIV education“. What are and what do you think about CDC sexual components (are they sufficient or not) and do these 24 states and the district of Columbia record fewer numbers of sexual harassment and sex crimes than the US average due to sex-ed?

I’m glad to hear that sex education is gaining support in Croatia! Sex education varies widely by state. There have been changes since 2014 and they are critical to understanding what can and cannot be taught. Sex education in the U.S. is up to individual states to administer. If states want to get federally funding for programs, they can only teach „abstinence-only-until-marriage“ (AOUM) or „Sexual risk avoidance“ (SRA) programs (the name has changed over time). Essentially, these programs must adhere to eight strict guidelines requiring instructors to teach only about abstaining from sex unless one is married. They also teach that having sex outside of marriage is psychologically and physically harmful—this is not true. Abstinence-only programs don’t work. In a study published in 2019 in the American Journal of Public Health, the authors show that abstinence-only sex education does not have an effect on teenage pregnancy; in fact, in conservative states, such programs have the opposite effect showing an increase in teenage pregnancy. In 2010, two small sources of federal funding were initiated that promoted sex education programs supported by evidence-based science (contraception, abstinence, sexually transmitted infections, and healthy relationships). These programs do work by lessening teenage pregnancies. Federally funded sex education is contentious and vacillates between support for programs reflecting religious values of abstinence-only and science-based interventions reflecting public health, particularly adolescent sexual health. Fortunately, there are other non-federally funded organizations like Planned Parenthood, the largest provider of sex education in the U.S. Their programs include topics like „communication skills, decision making, birth control, STIs, healthy relationships, consent, body image, anatomy, and puberty“.

In an editorial in the Journal of Youth Adolescence, the authors examine research from social and behavioral sciences in an effort to address more holistic sex education. They suggest that comprehensive sex education must also address gender and other structural inequalities. For example, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes that risk factors for serious health outcomes are related to sexual behaviors and violence in LGBTQ+ adolescents more than their peers. As Croatian leaders and educators begin to think about sex education, I would urge them to base programs on „scientific input from a broad range of disciplines, including social, behavioral, medical, and public health sciences“ as these authors suggest.

“Get off my pussy” Noćni marš (Night March) 2020 © Lara Varat

„Here in the U.S. is not much different“

Last year there was a quite gruesome verdict that caused quite a big controversy in Croatian public space. In the town of Čakovec in 2000, three 16-year-old boys were drinking in the afternoon in the bar in the company of a 16-year-old girl. After drinking they went to the family house of one of the boys and they raped her. The girl reported the crime after a week to the doctors who alerted the parents and the trial to the three boys began. The trial lasted for about 20 years. The girl has difficulties walking due to having cerebral paralysis as a child and the prosecutors charged the three boys for „forced multiple sexual intercourse with a person who is incapable of defense“. The experts, however, determined that the victim resisted the crime both verbally and psychically making the attackers clear that she didn’t want to have intercourse. She was crying and pushing attackers away“. Due to the fact that the girl resisted and the charge was that it was a forced multiple sexual intercourse with a person who is incapable of defense, the three attackers were ruled as not guilty and clear of all charges. Additionally, the Ombudswoman for gender equality Višnja Ljubičić warned in Croatian media following the „Nisam tražila“ initiative, there are only a couple of guilty verdicts for perpetrators of sex crimes annually, and instead, these verdicts often go in favor of the perpetrators. What is the situation in the US? Does it also take such a long time for the court to give a verdict for sex crimes trials are prosecutors also making such mistakes, and does the US have any sort of a legal mechanism that prioritizes sex crime trials?

The case you describe in Čakovec is appalling but I’m afraid that the situation here in the U.S. is not much different—there are equally horrifying stories here. As you might imagine, the question of time for sex trials and judgments in favor of perpetrators is quite complex. However, I will share some findings outlined in this 222-page report. The authors note that attrition rates for sexual violence in the criminal justice system are substantial and „most victims never receive closure.“ It is already well-established that most cases are never reported. Those that are reported rarely end in arrest and even fewer go to a trial 1.6%. These data are corroborated by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). They report that perpetrators of sexual assault are the least likely to go to jail than all other types of crimes.

Sexual assault is based on control and power. Our governments, educational, legal, and other social systems need to acknowledge and address the sexist, racist, classist, ableist, homophobic, and other forms of discrimination inherent in them. Otherwise, laws will simply continue to exist on inequitable systems and perpetuate discrimination.

But overall, are these problems bigger in Croatia than in the US or other western countries? The maximum sentence in Croatia is 10 years for rape and up to two years for sexual harassment while the highest legal prison sentence in Croatia can be 40 years. Is this sufficient? What would be, in your opinion, the most sufficient prison time for these crimes?

Our focus on punishment keeps us locked in a system that perpetuates harm and does not allow for the possibility of structural change. Do I think that perpetrators should be held accountable for their actions? Yes, I do. However, prison does not necessarily deter people from committing crimes and recidivism is a problem. Instead, the focus should be on prison reform, restorative justice, and the prison industrial complex (PIC) that uses policing and imprisonment for social and economic problems.

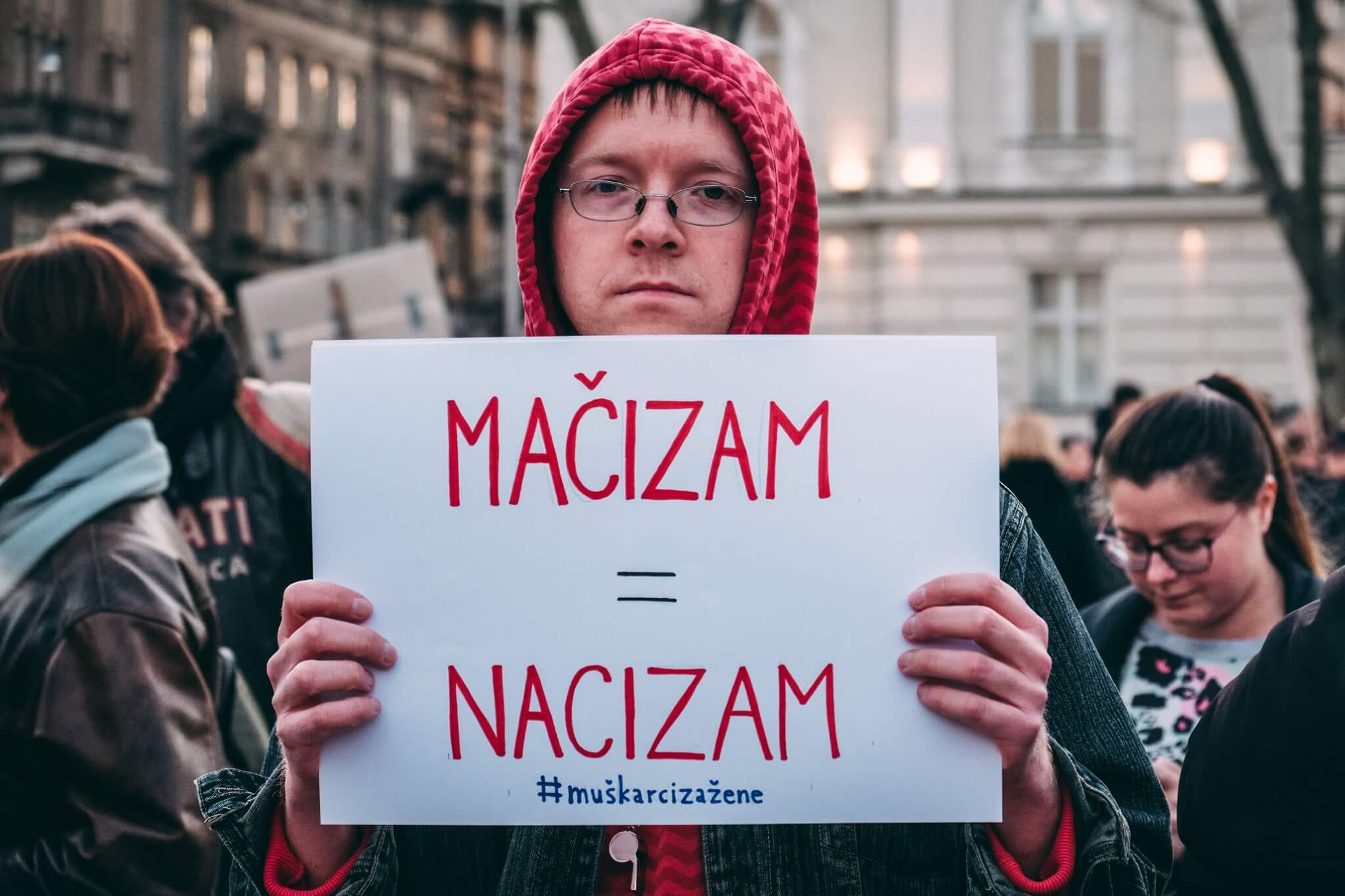

“Machoism = nacism #maleforwomen” Noćni marš (Night March) 2020 © Lara Varat

Equality vs tradition & faith

The majority of Croatians are proud of their traditional way of life and this tradition does play a huge role in the tourist promotion of Croatia that attracts visitors. But these traditions do come with a patriarchal structure and gender inequality as with other negativities that make the liberal stream roll-their eyes or down-right enrage them. Is it possible for Croatia to keep the traditions, its charm and yet create a society that does not discriminate on any level, including gender, religion, etc?

It’s absolutely correct that certain traditions come with gender inequalities within a patriarchal system and Croatia is not alone in this. It reminds me of an essay („Chiefing in Cherokee“ reprinted in The Best American Travel Writing, 2017) by Stephanie Elizondo Griest I read prior to coming to Croatia for my sabbatical. She addresses this question of capitalizing on culture versus wondering if one’s „touristic experience was authentic or not“. Tourists want „authenticity“ (tradition), but does it simply perpetuate discrimination based on harmful gender and other stereotypes? After all, tourism brings in money. I would like to answer this question based on one of many experiences I had in Croatia which I wrote about in my blog. I was grateful to be introduced to a tour guide who not only knows the history of Dubrovnik and Croatian tradition but can personalize her tours to include her knowledge of historically marginalized groups (the Jewish community, women, orphans, etc.) and how those forms of discrimination currently manifest themselves. I am not alone in wanting to be exposed to Croatia’s charm but also how its complex history mingles with current forms of discrimination. I think that creating a society that does not discriminate is possible and acknowledging past injustices is part of that process.

You mention your Croatian roots and the catholic origin and how you even studied in a Jesuit school that is quite progressive. The biggest opposers to Sex-Ed in Croatia are conservative Catholic politicians and thinkers and some of them, without much success, are fighting for prohibiting the right to abortion in the country as well as limiting LGBTQ rights. Jesuits are not too popular in Croatia but what would you suggest, from a catholic position to the Croatian Catholics how to reconcile their faith with sexual education, LGBTQ rights, and women’s reproductive rights?

When I was a child, I distinctly remember a lesson from catechism about baptism and limbo. I learned that if a baby were to die before being baptized, they could not go to heaven (baptism being a prerequisite after all). This bothered me…immensely. I questioned the doctrine—„do you mean that if a person in another country who isn’t Catholic and has never even heard of baptism can’t go to heaven even if they have been a good person?“ The answer, a firm „no“, made no sense and I was admonished for asking more questions. Of course, the Catholic church got rid of the notion of limbo some time ago, but the hypocrisies of my childhood religion were not lost on me. Although I did not have the language at the time, I was asking questions about privilege and the very foundations of systemic injustice. These answers weighed heavily on me as a child as I gravitated to the lessons of love and forgiveness.

I share this story because grappling with any belief structure, including one’s religion, has been part of who I am. Reconciling one’s faith with injustice is a personal journey and for me, doing the moral and right thing did not coincide with some tenents of the Catholic faith. I was not really allowed to question doctrine until I entered college and was exposed to Jesuit education that is rooted in service, justice, and love. I was taught to critically think about rather than accept doctrine. I write a bit about this in my blog in trying to understand Catholicism with the general lack of volunteering in Croatia.

The truth is there are conservative and progressive ideas that inhabit all social institutions—family, government, and religion. There is a Roman Catholic axiom, Imitatio Christi, which is loosely translated to a popular phrase that came into English usage in the 1990s, „What Would Jesus Do?“. If your answer to this question urges you to act with humility and compassion then perhaps there is room in Catholicism for inclusion and education (including sex education) based on teaching healthy relationships and nonviolence.

prof. Mala Matacin in Dubrovnik / private archive

To conclude, as someone coming from the US in the middle of getting Croatian citizenship, do you feel you will be more discriminated against in Croatia for your gender than in the US? Given your participation in “Noćni marš” and your knowledge do you think that as a Croatian citizen you could help improve the gender equality in the country both with your knowledge but also with experiences and background from the US?

It is my sincere hope that I will be able to get my Croatian citizenship! I met many people during my sabbatical who are doing important work to improve gender equality in Croatia and I would be honored if I could contribute to the ongoing efforts. I did not feel discriminated against based on my gender in professional realms in Croatia. In fact, a great majority of those doing gender-related work are women and I felt a kinship with them just as I do with those in the U.S. However, I know that women are discriminated against despite that it is not as overt as it once was (e.g., a woman not being given a job because of her sex). Research on implicit bias supports this.

Project Implicit is a non-profit organization founded by Harvard University in 1998. Implicit biases are deeply held attitudes and stereotypes about certain groups of people. „People can act on the basis of prejudice and stereotypes without intending to do so“. Despite the gains women have made globally, social science research supports that implicit biases are related to discrimination in complex ways. For example, a recent study showed that men are more likely to be seen as „brilliant“ than women across 79 countries globally. One of the authors states that “stereotypes that portray brilliance as a male trait are likely to hold women back across a wide range of prestigious careers”.

It’s not discrimination, but I noticed that my gender mattered differently in Croatia in terms of marital status and traveling alone. Initially, I was taken aback by questions about my marital status (for example, „where is your husband?“) or why I was in the country by myself. Such questions are not normally asked of me in the U.S., particularly among people who I meet in casual, public spaces. Yet, in Croatia they seemed natural and okay to ask—it felt unsettling to me.

For more about politics in Croatia, follow TCN’s dedicated page.