We live on an island. We could say the ship came first, the islanders second. One had to build the ship in order to arrive at the island and become an islander. A fascinating insight into the shipbuilding tradition on Murter island in the Betina museum

Earlier this week, I had the pleasure of participating in the latest Gastronaut culinary tour, a three-day trip around Murter island and national parks Kornati and Krka. Take an enthusiastic crowd of restaurateurs, journalists and all-around hedonists, add an abundance of gourmet delights we’ll make sure to present in the coming days, and you have yourself a spectacular journey on its own. And yet, the experience was made even better by an additional factor that goes beyond the scope of fabulous Croatian gastronomy: a fascinating glimpse into the complex reality of island life.

Widely regarded as attractive summer destinations, Croatian islands evoke a mesmerising image of a surreal dimension where time slows down; far from the mainland, on these little snippets of paradise, it’s easy to get drawn into a laid-back, tranquil state of mind and forget the hardships that await once the summer is gone and the tourists have left. Even before the dawn of tourism in Croatia, the island residents always had to mend for themselves, without any outside help or support. People used to live exclusively on what they could grow or build; they would tend to their crops, selling produce in neighbouring villages or on other islands, swapping what they couldn’t sell for various goods.

In such a context, shipbuilding was an activity crucial to survival. Sailing didn’t represent just a means of transport, but literally enabled the island population to make their living: families who had estates on other islands in the archipelago simply had to own boats in order to reach and tend to their land.

Knowing that Murter island boasts an incredibly long shipbuilding tradition, I was thrilled by the opportunity to visit the Museum of Wooden Shipbuilding in Betina town. Having visited the Batana Eco Museum in Rovinj earlier this summer, I was looking forward to gaining some more insight into the history of boatbuilding on the Croatian Adriatic, this time at an institution paying tribute to countless generation of craftsmen from Murter.

Stepping into the museum resembled opening a treasure chest: amidst the quiet streets of Betina, just a couple of steps away from the waterfront, lies the perfectly preserved townhouse whose two floors house a stunning display. Greeted by the lovely hostess Mirela who took us on a guided tour of the place, we were instantly won over by the tickets alone: instead of a regular museum ticket, we were presented with replicas of muril, a flat wooden tool local shipbuilders use to precisely determine proportions of all the parts of the boat. An innovative way to introduce visitors to the story and a token of remembrance to take home – a simple gesture, yet enough to make a place memorable.

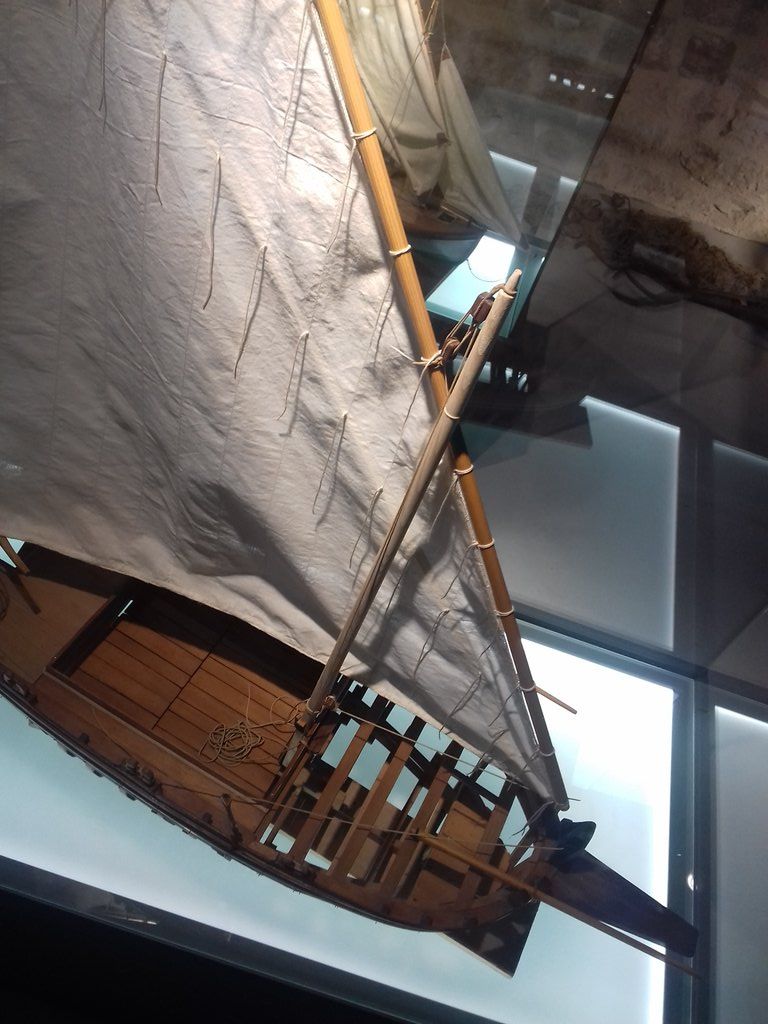

A gorgeous model of the wooden gajeta boat in the anteroom is accompanied by an animation depicting the process of assembling all the individual parts – no less than 49. The technical complexity of construction, combined with the aforementioned importance of boats for the island population, makes it obvious why shipbuilders enjoyed a prestigious reputation in the local community. The civil register and parochial books preserved in Betina show three professions were held in high regard: doctors, teachers, and shipbuilders, all of them holding the title of maestri, masters of their respective crafts.

The first known shipyard (škver) on Murter island was founded in the 18th century by the Filipi family who moved to Betina from Korčula. As the island was inhabited as early as in the 13th century, shipbuilding activity must have been flourishing on Murter even before the first registered škver started operating, but there’s no preserved documentation to provide us with more information on the island’s history.

While the population of other Croatian islands and coastal towns mainly engaged in fishing, residents of Murter were mostly farmers and cattle breeders, which is why the shipbuilders had to adapt a typical fishing boat into one whose main purpose was to transport various kinds of cargo – produce, livestock, and construction material. The Betina gajeta is thus known as a robust boat with a flat keel and a straight frame, measuring 5-8 metres in length and around 2 metres in width.

Shipyards ran by the families Filipi and Uroda manufactured wooden boats for the area laid out between Zadar and Šibenik; by 1926, there were one major and nine small shipyards operating in Betina. Here’s a statistical fact to illustrate the importance of Murter when it comes to the shipbuilding industry: at the time, all the shipyards in Betina covered a surface of 11.200 square metres in total; all the other shipyards in northern Dalmatia put together came down to 10.330.

Chamber after chamber, the museum surprised and delighted in equal measure. What could have been a somewhat dry display of factual information was ingeniously combined with interactive installations, videos, games and reconstructions of various types of boats, resulting in an attractive assemblage of exhibits that is sure to keep you transfixed through the entire visit. All of that presented in an authentic ambiance of a traditional stone house, enabling us to immerse ourselves in local history and learn more about generations of people who treated their boats both as valued possessions and family members. People lived in unison with their gajetas, and there was no living being on the island who didn’t know their way around a boat: sailing to other islands or the mainland implied women taking care of rowing so their husbands wouldn’t get too physically exhausted to work on the land overseas. This particular tradition lives on to this day, with ladies of Betina taking part in the annual women’s rowing regatta called Dlan i veslo (Palm and Paddle).

Once you’re done with the tour, you can test your newly acquired knowledge and try your hand at assembling a gajeta in video game designed exclusively for the museum. Visiting with kids? There’s a special, somewhat simplified version of the game for children, and they’d certainly enjoy trying to score a place in the digital shipbuilding hall of fame. You’ll also find an art corner, and the museum regularly holds workshops both for kids and adults. Round up the experience by getting some souvenirs to remind you of your visit; there’s an abundance of postcards, artwork, shirts, jewelry and lovely boat models to choose from.

Betina Museum Facebook

Make sure to take a walk around Betina to get the full picture of the shipbuilding tradition. On the waterfront, you’ll be greeted by Cicibela, a gorgeous example of the typical gajeta that prompted the Ministry of Culture to inscribe the art of construction of the Betina gajeta in the list of intangible cultural heritage.

The highlight of Betina’s shipbuilding story takes place in August with their Regatta for Body and Soul (Regata za dušu i tilo); the giant fešta might be the best time to experience this incredible place, its population and their heritage, but it was equally awarding to visit the town in November. In spite of the rain and cold, the blinds closed and the streets vacant, there was a certain magical vibe to walking around this charming town. On my part, I’ve never been more glad to have woken up at 6.30 in order to visit a museum.

Betina Museum Facebook

You can find more information on the museum’s official website and follow their activities on their Facebook page.