When I bought my house on the island of Hvar 20 years ago, several of my good friends were quite angry with me. What is wrong with you, Paul?

I smiled.

I could understand their concern, and I smiled again. Six weeks before buying the house, I was working as an aid worker in northern Somalia, with regular trips to the self-proclaimed Autonomous State of Puntland – the part of the Somalia where those fearless Somali pirates hang out and where they like to kidnap white boys for fun. I had an armed guard called Arafat every time I left the compound, and my job took me to some very remote parts of bandit country, some of which have still not really been discovered by Google.

(Life in the forlorn deserts of Puntland, Somalia, back in 2002)

Before that, I had been an aid worker in Rwanda straight after the genocide, worked in some questionable parts of the former Soviet Union soon after its collapse, and managed to get in the middle of a gun battle between the Israeli and Palestinians in the West Bank. There were only two words to describe me, decided my friends (incorrectly, as it happens) – war junkie.

And here was the latest proof – I had bought a house and decided to move to a war zone, Croatia.

The year was 2002 and I could understand (and appreciate) their concern, but I had to smile again. I don’t think I had been to anywhere as safe, as calm, or as beautiful as this idyllic island, whose name I had learned just 2 days before. The day we arrived in Jelsa, we went to a tourist agency to find accommodation – it was peak season. A phone call was made and 5 minutes later, a cute girl no older than 6 with a few words of English turned up. The agency explained that she would sit in the front seat and guide us to her grandmother’s rental property in the old town. Which she did with aplomb. And then she ran off to play with her friends.

A war zone indeed. The reality was, however, that Croatia had been at war just 7 years previously, although there was no fighting on the island, apart from a couple of bombs dropped on the airport (the influx of refugees and naval blockade is a different story) and I was still dealing with customer enquiries about safety and war on Hvar a decade later – perceptions take time to change.

And so began what on reflection was my first tourism promotion of Croatia. I sent photos and explanations. And invitations. I went to work in Hiroshima for 6 months, teaching English, French, German and Russian in Japan, and I invited friends to come and stay for free to experience my hidden gem of a war zone. The house was full, perceptions were changed, and several friends became regular visitors to Croatia, with one even buying his own house on the island.

I settled down into life in my new home, an amazing community that supported each other. Kids running around on the square under the watchful eyes of mothers enjoying a coffee in the sun, schoolkids the age of 7 walking halfway across the town to school unaided, young women walking home alone unhindered after midnight. There was no crime and I, liked most of my neighbours left cars and houses unlocked. I didn’t carry a key in my pocket for years, and one of the many joys of living in such a safe environment was to find a bag of fresh fruit or vegetables gifted to you on the kitchen table by a neighbour returning from their field. I didn’t go as far as to leave the windows of the car down due to the heat, with the keys in the ignition, but plenty of my neighbours did (and still do).

My kind of war zone.

From being on guard to sudden movements in a Somali town, I became the most oblivous person to security. This place was easily the safest place I had ever lived – it even felt safer than during my time in Japan.

There was almost no crime at all. And when there was, it made the regional news. One could imagine how dangerous this place was when the regional news had a front-page story in about 2003 on the theft of 50 litres on Hvar. Time to lock those doors.

Inevitably things have changed a little, and petty theft is now sadly an occasional reality, and so more doors are locked these days, but it is a far cry from having a knife pulled at me in the park in Manchester on my way home at uni. Indeed, in all my 20 years in Croatia, the biggest crime I can recall being a victim of was due to my unlocked car. We had been with friends in Hvar Town and they had gifted us a freshly-caught fish. I ran into town with the kids to buy a birthday present for a party they were attending, leaving the car unlocked, the fish on the back seat.

When we returned, the fish was gone, as was the kids’ backpack containing their swimming things. So outraged was my 6-year-old that she insisted on calling the police to demand an investigation. The police said that they would do all they could, but that perhaps Daddy was at fault. She blamed me for the loss of the rucksack, and she insisted I always lock the car thereafter. She didn’t seem to feel my loss of what looked like a VERY tasty fish.

Another key part of the safety in Croatia is the sense of community within generations and within itself. Mums know that if they have a coffee on the square that they can relax and keep just a cursory eye on the child playing. If the child goes out of sight, it will always be in the sight of a neighbour or friend, who will quickly check if something does not look quite right. I lost my daughter one day on the square when my back was turned and spent 5 minutes in panic searching. And then the phone rang – Teta Josipa from Me and Mrs Jones restaurant, the other side of the harbour. Your daughter is here, she wanted an ice cream, and when I asked her, she said she forgot to tell you. Are you coming too, or shall I send her back when she has finished? On the way a couple of neighbours had seen her walking alone and asked if she was ok – she explained she was going to visit her aunt at the restaurant for an ice cream.

Priceless.

And more and more people, especially from the Croatian diaspora, are beginning to make important decisions based on the safety of Croatia – moving back to the Homeland to bring up their kids in a much safer environment than they can find in Western cities. I have come across 5-6 Australian families with Croatia roots who have chosen Croatia over Sydney, for example, for one reason and one reason only – safety. And as the world continues to go nuts, and the culture of remote work grows, this is a trend that is only going to increase.

Another trend I am seeing on my travels is of increased real estate activity of white South Africans, who are looking to move from their home country due to the deteriorating situation back home. Croatia is the safest and most welcoming country they have found for their needs, and they are buying.

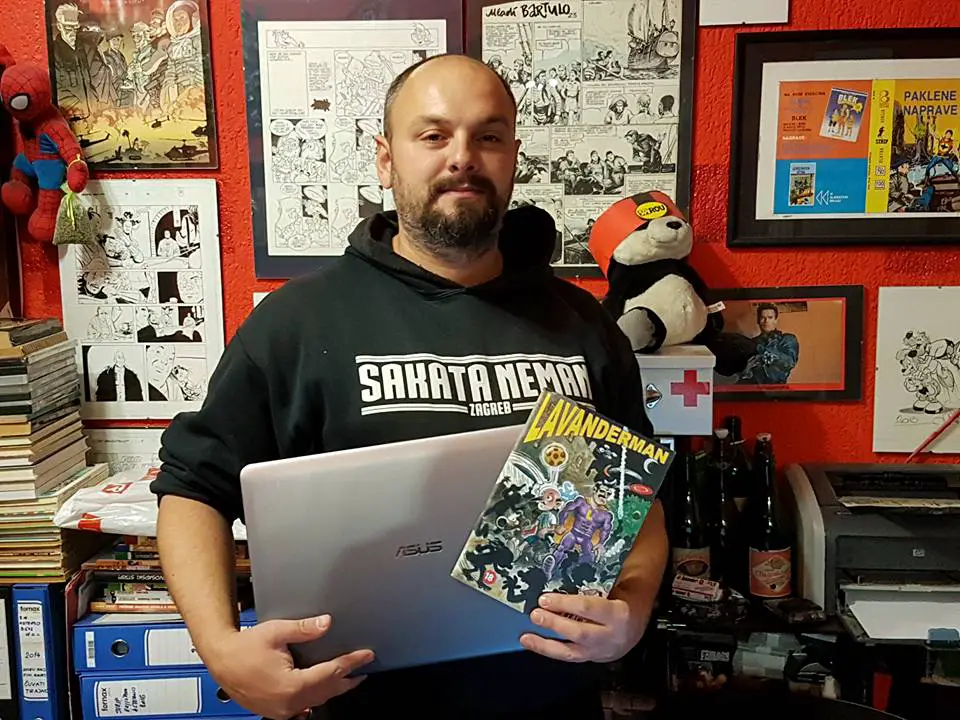

There is another very important (and rarely referred to) aspect of safety in Croatia – the kindness of strangers. There are countless examples of a tourist forgetting his wallet at a restaurant, or dropping it in the street, only for it to be returned with all money inside. In my case, I have one anecdote which for me perfectly explains why Croatia is one of the best societies to live in today for its values of decency and safety (we will leave the corruption and macro-theft of the nation’s wealth aside, for this article is about lifestyle and personal safety), a really heartwarming story that you can read in full in Losing a Laptop in Zagreb: the Kindness of Strangers.

A few years ago, while living in Varazdin, I was on one of my business days in Zagreb, which included what turned out to be quite a boozy late morning office party. As I left and continued my day, someone packed a few beers in my bag that were left over from the party. I continued my day, with one bottle falling out onto the street as I got out of a taxi. I got home late, put the beers in the fridge and went to bed.

The next morning, I woke up a little groggy and with a writing deadline to meet. I made a coffee and opened my bag to fire up the laptop. The laptop was not there! I retraced my steps and wondered if I had left it in one of the cafes (I called each), and I even checked the fridge to see if I had drunkenly put it there. The laptop (and therefore most of my life) was gone. I had no idea what to do next.

And then a message on Facebook. Was I the Paul Bradbury who had lost a laptop in Zagreb yesterday? Joy at knowing the laptop was found, terror at how much ransom I would need to pay to get it back.

But this was Croatia, and I need not have worried. A very nice man had been walking with his friend for a coffee and found the laptop on a street in central Zagreb (where the bottle had fallen out), picked it up, opened it and found my name on the login details. A search of ‘Paul Bradbury Croatia’ indicated that I might be the owner. My new best friend told me that the laptop had suffered a little damage but that he had managed to fix that for me, and that I was free to collect it any time at his comic shop. I packed the beers back in the bag as grateful payment and gratefully headed to Zagreb. How many capital cities would that happen in?

Twenty years on, Croatia is no longer regarded as a war zone by anyone, but perhaps the time has come to tell people just how safe it really is, especially as this is a key factor for many in the remote work revolution.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning – Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email [email protected] Subject 20 Years Book