I am pretty good at languages, but I gave up in Croatia.

But not for the reasons that you might think, for I genuinely think that the Croatian language is easily the most logical that I have ever attempted to learn, with the possible exception of Esperanto.

My Russian was pretty good, and I was comfortable enough to give live television interviews on the recommended uses of peanut butter on the edge of Siberia (don’t ask) in 1993. My French peaked in post-genocidal Rwanda in 1995 when I was asked to educate the Minister of Agriculture on the benefits of planting Brussels sprouts (again, don’t ask). And my German was polished as a bell boy on the night shift of a very posh 5-star hotel in Munich, where my duties ranged from explaining the whims of guests such as The Rolling Stones to arranging ladies of the night for German public figures (please, really don’t ask).

And then came the Croatian language, or at least the variation of it to which I was exposed.

First, the good news for those wanting to learn Croatian. I firmly believe that it is one of the most logical languages in the world. And I mean that sincerely.

Once you have learned the Slavic structure of language (and that is the tricky bit), there are relatively few rules or exceptions in Croatia, and they can all be learned.

For example – ‘k’ followed by ‘i’ always goes to ‘ci’ – Afrika but u Africi, that kind of thing. Learn the Slavic structure of language (as I had with Russian) and those few exceptions, and you are home.

I will never forget watching my daughter learn to read in Croatian at the age of about three. It was one of the most extraordinary things I have ever witnessed. And not just because she is my daughter.

She picked up the alphabet very quickly, and then she started to write the letters. Tell me some words, she said. Pas (dog) – she wrote it perfectly. Kuca (house), again, not a moment’s hesitation. I made things a little more complex every time, but without a moment’s hesitation, she produced the correct spelling.

Strpljenje (patience) I said, fast-forwarding the task by a few layers of complexity. I hadn’t finished uttering the word almost before she wrote it down flawlessly. It was an incredible spectacle, and I was very proud of her.

“How about the English word for osam (8)?” I suggested, trying to regain the intellectual superiority.

When I showed her that we spelled it E-I-G-H-T, she looked at me with innocent blue eyes and said:

“That is silly, Daddy, and so is your language. Mum’s language is so much better.”

I couldn’t argue with that.

Phonetically, Croatian is the most regular language I have come across. What you see is what you pronounce. So if the language is logical and the pronunciation is predictable, why did I give up with the Croatian language when I had mastered other languages?

Two reasons. Those j*beni dialects, as well as the excellent English spoken by most Croatians.

When I first moved to Hvar back in 2002, I decided to learn Croatian. My Russian background helped enormously with the grammar, and I borrowed a book from the library (meeting my future wife in the process) to help me learn, as well as taking private language lessons. It was a curious experience, as I had two teachers for just me. They were used to foreigners doing battle with the Slavic structure. As I had lost my nerves with that battle learning Russian, I sailed through their lessons, and they could not keep up, as their lesson plans had predicted the Slavic wall of non-comprehension.

I gave up and decided to learn my Croatian in the wonderful cafe culture of Jelsa, over a beer or three. And I got to be pretty good.

Or so I thought, until I went to Zagreb on business as a real estate agent. The Croatian client wanted to buy a house on Hvar and asked me the price over a coffee on Ban Jelacic Square:

“50 mejorih,” I replied.

He looked at me blankly and asked me to repeat. I did. He was lost. Thinking it was something to do with my atrocious accent, he asked me to write it on a piece of paper. I did so. 50,000.

“Ah 50 tisuca,” he exclaimed – the very same word as in Russian. A horrendous realisation came over me. I had not been learning Croatian in the cafe at all, but rather some obscure Jelsa dialect.

It turned out that my word for thousand (mejorih) was actually a dialect word used only on Hvar – and not even on every part of Hvar. Take the catamaran to Brac, and they wouldn’t have a clue what you are talking about.

What had I done? What had I been learning all this time? A useless language which could only be understood by about 2,000 people.

It got even worse when I started researching things a little. Croatia is FULL of dialects, not in the way the UK is, but they really speak almost different languages. On the island of Hvar, for example, there are apparently 8 different words for chisel. The bigger joke being that you cannot find a chisel to save your life even if you know all 8 variants.

I finally gave up on the Croatian language in about 2012 on a business trip to Split. For some reason, over a coffee with my business contact, we were discussing the merits of hanging out laundry to dry. It was not a subject on which I had a lot to contribute, but I did pick up a new Croatian word from the conversation, the Croatian (or what I thought was Croatian) word for the humble clothes peg – stipunica.

Arriving home on the catamaran, I had a coffee with my lovely mother-in-law on the terrace. She speaks no English and so we conversed in Croatian, with her asking me about my day. I told her that I had learned a new word – stipunica. She looked at me blankly. Finally, I got up from my chair and went to find a clothes peg to demonstrate what I had learned. She smiled.

“Ah, stipaljka.”

I gave up.

Especially as the Croatian non-dialect word for clothes peg is apparently ‘kvacice.’

English was so much easier, especially with the outstanding level of English spoken by most Croatians here. It is really impressive.

I can and do speak Croatian (much to my daughters’ embarrassment) but I spoke it a lot better ten years ago than I do today. The level of English is simply too good, and I have got into the habit. There is one occasion when I do speak Croatian, however, and it always gets a laugh – when I speak at a conference or am interviewed on television. I always start with the following to a Croatian audience (translation to follow):

Ako Vam ne smeta, ja cu dalje na engleskom zbog punice. Imam najbolju punicu na svijetu, i prije nekolilo godine, ona je dala meni neki savjet. Ona je rekla “Zete, ja te jako volim i slusam te vec 13 godina, i zbog ovag ljubava, je sve razumijem kad ti pricas. Ali samo zbog ljubava. Imam jednu molbu od srce. Kad ti si na televiziju ili konferenciju, samo na engleskom, zato izvuces kao neki kreten.

(If you don’t mind, I will continue in English due to my mother-in-law. I have the best mother-in-law in the world, and she gave me some advice a few years ago. She said “Son, I love you very much, and I have been listening to you for 13 years, and because of that love, I understand everything when you speak. But because of that love, I have one request from the bottom of my heart. When you are on television or speaking at a conference, only in English, as honestly, you sound like an idiot).

I can’t disagree with my punica… but the sentence is a hit. It always gets a laugh and breaks the ice and shows that I respect the culture to at least try and learn the language. And then I can relax and continue in English.

Nobody has influenced my time with the Croatian language more than the man who helped me learn a completely different language than Croatian without telling me – Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects. Of the few things I have achieved in my 20 years in this beautiful land, taking the Professor from a silly idea over a coffee one October to a TV star on British television makes me smile the most.

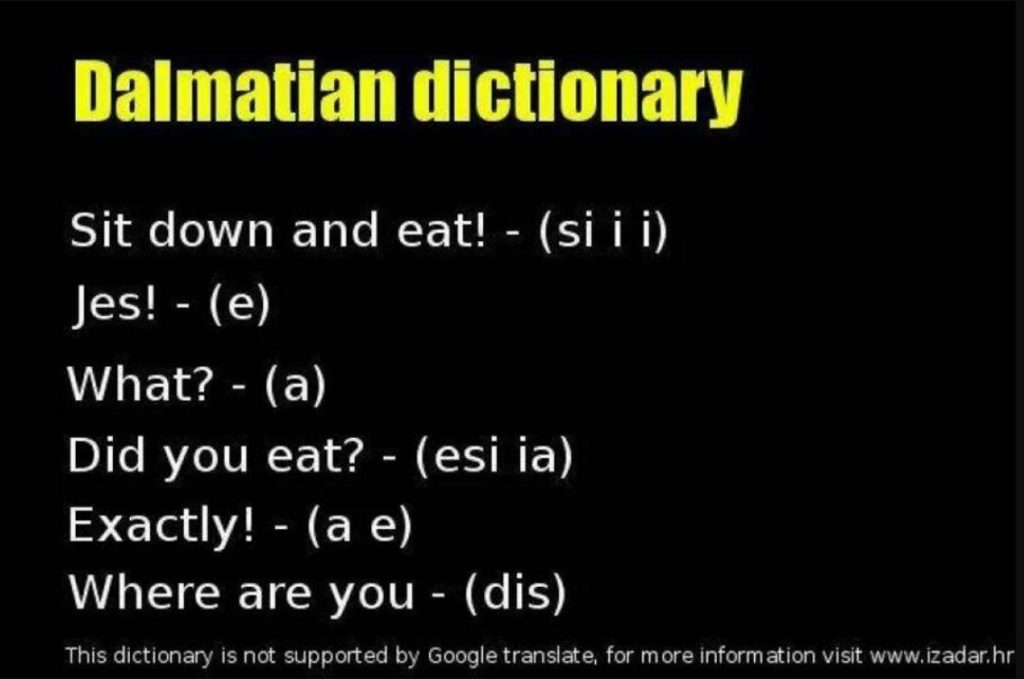

Frankie is a Jelsa legend. Born in New Zealand, he moved to Jelsa at the age of 8 when his Croatian family decided to move back to their homeland. He has always been trilingual (English, Croatian and Jelsa dialect) although I am sure I am not the only one who cannot work out what language he is speaking half the time. He is well-known in the community for his enthusiastic greeting of people from distance – perhaps the finest example of what I coined the Dalmatian Grunt.

And so began a journey which saw the Professor beamed into the homes of millions in Britain.

One morning, we happened to have a camera with us, and so I suggested we film the Dalmatian Grunt in an educational language video. What happened next was extraordinary. The original posting of the video above quickly amassed over 50,000 views (mejorih or tisuca…) on YouTube, and the comments were gold. He sounds like Uncle Ante, who moved from Dalmatia to Australia 50 years ago, that kind of thing.

Suddenly, we had a cool concept. Highlighting the differences between standard Croatian and Hvar dialect. We had so many topics – vegetables, months of the year, articles of clothing. We had guest dialect speakers, such as these chaps from Dubrovnik – a lesson of Hvar and Dubrovnik dialects and standard Croatian which proved beyond doubt that learning Croatian made no sense whatsoever.

Our fame was growing.

And when the deputy head coach of the Australian soccer team, Ante Milicic, contacted me for a request to meet the Professor, I knew we were onto something. Ante confided to me that he was a little obsessed by the Professor and had his voice both as his phone ringtone and alarm, as you can learn from their first meeting below.

But the best was yet to come.

National television got in touch. They were coming to film a show called Susur, an hour of tourism promotion of Jelsa on prime time television. They wanted to feature the Fat Blogger and record him eating blitva (Swiss chard) and also have an exclusive lesson with the Professor.

The Professor answered the call with a majestic display of dialect words for wine, finishing with an even more majestic Dalmatian Grunt for the nation. You can see it all below, starting at 02:16.

The Professor was getting mobbed on the streets of Zagreb by his increasing (and mostly young and female) army of fans, but the best was yet to come. Among the pearls in my inbox one morning was a request from a British reality show to engage the Professor’s services to teach a little Croatia to the show’s participants.

To watch about a dozen Brits practising the Dalmatian Grunt on national UK television under the Professor’s dedicated supervision on a beach in Zaostrog was genuinely one of the highlights of my life.

The Croatian language at its finest.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning – Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email paul@total-croatia-news.com Subject 20 Years Book