Interview with Mirko Sardelić, Ph.D, Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

Intro: The human species has a unique capacity in terms of abstract thinking and innovation. Our civilization has advanced as humans developed new creations. Now, we are living in times when the speed of innovation is faster than ever, when the reach and the adoption of every new technology is quicker and wider than ever before. Still, on the one hand we have small but very innovative countries; on the other hand, some countries are quite big in terms of size and highly populated, but still falling behind. In this interview, we will discuss which technologies and discoveries changed the course of history and the balance between societies and countries.

Q1: What were the first discoveries that happened at the dawn of our civilization? How long did it take for them to spread around the globe?

From today’s perspective when we think about technology, the things that come to our mind are often connected to electronics, robotics, or nanotechnology. But in order to get to these advancements, some simple yet fantastic discoveries shaped the way humans made the environment much more hospitable, or safer. If a community wanted to protect itself, its members needed fortifications such as walls and fortresses. If they wanted the fortifications to pose a serios obstacle, they made them of big blocks of stone; and this was not just in ancient times. How does one transport these huge blocks much easier? By rolling them on tree trunks, forming slides of some sorts, with humans or animals pulling ropes. Tree trunks are round, they roll nicely across the terrain; and if you cut just a piece of a cylinder, you get something which can be called a wheel. Four kinds of independent evidence for the use of wheel for wagons appeared across the ancient world between 3400 and 3000 BCE. The wheel has had an enormous impact in human history; however, there were some advanced civilizations, such as the ones in South America, that did not use it.

One tends to overlook the importance of the screw, the last of simple technologies invented, some 3000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Just check out modern machinery and you will see how bolts and screws keep those machines together. In Mesopotamia and ancient Greece screw pumps were used for irrigation, i.e. to transport water. One can also mention nails, a simple and yet a very important element that binds things together.

In terms of processes that are more complex, I believe that the development of metallurgy had a huge impact on these later stages of human evolution – it got us out from the Stone Age anyway. In order to be able to shape bronze, humans first needed to develop the technology of furnaces capable of maintaining the temperature around 1000 C. Arguably the oldest Bronze Age cultures were in the Balkans, around the Danube basin, some 6000 years ago. Bronze was a great asset when it comes to making tools and weapons. Bronze weapons were crucial in combat – many wars were won just thanks to this improvement. Around 1700 BC the people from western Asia called Hyksos used their bronze weaponry and chariots to conquer not just any kingdom, but the grand Egypt whose infantry was fighting the war while equipped with copper swords.

As far as the circulation of these inventions is concerned, resources of information, innovations and techniques accumulated in each region sooner or later found their way throughout the Afro-Eurasian zone. The exchange and transfer of knowledge in this vast continental mass was quite intense; however, it took up to several centuries for some technologies to get introduced to various places during the Metal Ages. Conversely, three other inhabited continents were left out of this flux.

Q2. Was there a discovery that helped our civilization to mature and form the concepts that we see today – countries and nations?

This is quite a broad aspect. Let us begin with agriculture and domestication of animals that are closely connected with sedentary cultures. Farmers started planting grains some 10-12.000 years ago, and not much later (probably some 10.000 years ago), sheep, pigs and cattle commenced their cohabitation with humans. Food surpluses allowed the creation of the first cities, in Mesopotamia and South Anatolia, before 7000 BCE. Requisites for agriculture were favourable climate and access to water; the latter was acquired through, among other means, irrigation, another great invention. In river valleys and swampy terrains of Egypt or Southeast Asia one could use digging sticks to create seed drills, but harder soil craved for the invention of ploughs.

Cities became centres of economic, political, and religious activity. Let us just remind ourselves that 55% of the world’s population today lives in urban areas, which is projected to be close to 70% by 2050.

As for spiritual activity, Christian and Buddhist societies of the Eurasian continent experienced the important invention of the monastic life. An order of men detached from quotidian social connections, eminently mobile, dedicated their life to specialization in the highest intellectual or spiritual discoveries that contributed significantly to their societies.

Nations are imagined political communities, mostly formed in the 19th century for various reasons; mostly aiming political stability that ensures all other activities to develop in what is perceived a safer, more homogenous environment. In principle, the institutions of national governments are trusted with nation’s defence, education, legislation, civil rights, foreign relations, transport infrastructure, and a whole set of tangible and intangible structures that enable complex social activities.

Q3. What were the main historical discoveries and innovations that started new epochs of development?

The first that comes to my mind is the one that marks the beginning of history: the invention of writing. It was invented in several different places independently, first in Mesopotamia and Egypt (ca 3200 BC), then in China (1500 BC) and Mesoamerican cultures. In the beginning, it was used mostly to record the most important information related to agriculture or taxation, but later on it developed into an indispensable tool to transfer ideas; in short, this included anything worth remembering and developing. Manuscripts were circulated across the Afro-Eurasian world for centuries, contributing to development of ideas and technologies. Writing is the embodiment of ideas, but it is much more than that: it has a cognitive and social function. Therefore, we all continuously practice writing, we contemplate, polish, and revise our texts, i.e. our ideas.

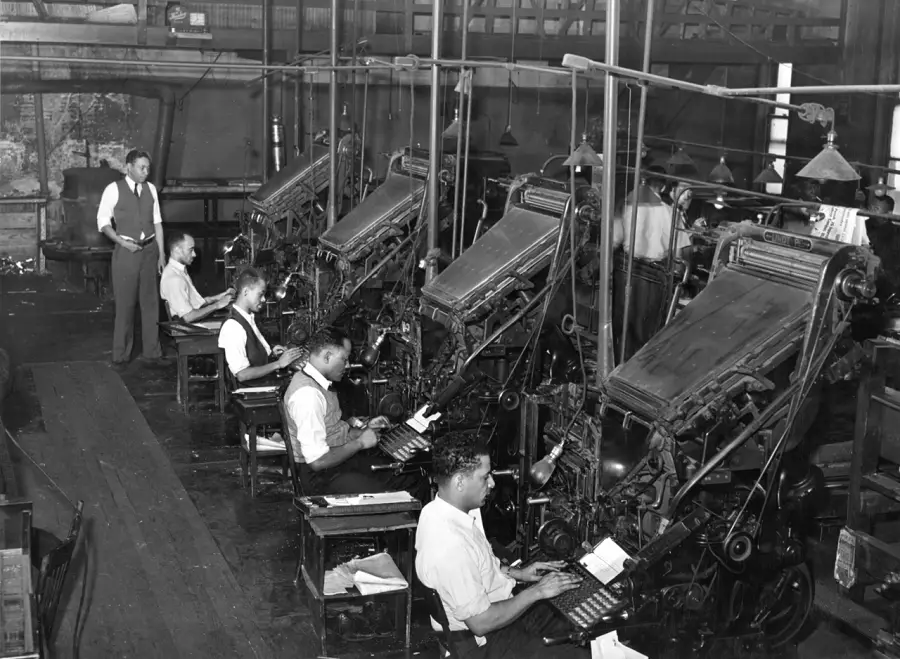

Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century made the written word the medium of mass communication and removed some limitations for the circulation of information. Books became more accessible, and more numerous: it is estimated that by the year 1600 some 200 million copies of various books were printed. One can only imagine how many more books eventually were printed over the four centuries that followed. A subsequent medium that appeared in the 17th century, the newspapers, shaped the world of information in the way that Internet and TV shape digital circulation today.

Q4. What technologies made the biggest changes in relations between the countries or continents, or changed their power relations?

The 18th century saw the invention of the steam engine. Its improvements in the 19th century gave birth to machines, which resulted in enormous advancements in industry, transportation, and agriculture. In turn, this gave base to the rise of superpowers such as Great Britain and the United States of America. High-pressure engines started setting ships, trains, cars, and eventually airplanes in motion. Steam engines powered the Industrial Revolution that shaped the world as we know it today.

Q5. With the development of new weapons, in the 21st century, the old ones are becoming increasingly obsolete. Tanks dominated in the last 100 years but are now becoming useless, mostly because of much cheaper drones. Was there a discovery or technology that empowered one country in war or a similar kind of conflict?

In one of our previous interviews, we mentioned that one who wants to win the war needs two requisites (to start with): the means to finance it and good logistics. In the present day, the development of new weapon technologies is more entangled with the financing of new ideas and related discoveries. But in the past, some very simple ideas lead to the creation of extremely powerful military units. Again, somewhat neglected from a modern perspective, chariots were a high-tech weapon some 3000 years ago. It is not directly connected to technology, but it is hard to overemphasize the importance of horses on warfare through at least four millennia of human history. Alright, some inventions such as the stirrup or the saddle made them more effective over time. Cavalry was a predominant force until the invention of reliable, fast, and powerful weapons at the beginning of the 20th century. For centuries European armies had difficulties confronting Eurasian nomads (the Huns, Magyars, Cumans, Mongols…) whose light cavalry used (composite) bows to launch thousands and thousands of arrows in a matter of minutes. Even one of the most successful military formations of ancient times, the Macedonian phalanx, needed cavalry on its flanks despite its 5-meter-long spears.

Composite bows and longbows were the light artillery for millennia. The mentioned steppe nomads dominated battlefields of Eurasia using exactly those kinds of weapons. English longbows were the equivalent in Western Europe in the Late Middle Ages (12th-15th centuries). Its ‘mechanic’ cousin, the crossbow, was so powerful and lethal that Pope Innocent II (1139) forbids its use against Christians.

Great wars of the 20th century significantly improved the weaponry, created nuclear powers and lead to the development of rocketry.

Q6. It is expected that much of the future warfare will be cyberwar. Many countries are developing their cybersecurity as a response. Has something similar to that process happened in history?

Technology made everything more accessible, which means not only physical protection is needed, but virtual protection has increasingly gained importance. One can use your credit card from another continent, skilful hackers can turn off the electricity to a block or even part of some remote town. It is a perennial question of access to information and those skilful enough to (ab)use it.

One of my main interests are nomadic empires, so I will draw two examples from the rise of the Mongols. Once they had established the empire, they realized that they should use all skilled workers they encountered and captured in their campaigns. The Chinese had very capable engineers who could build impressive structures or produce war-machines, the Persians had experienced administrators (…) – all those were used to do the things nomadic peoples were inexperienced in. I believe this is a great example of being aware of one’s own limitations and knowing exactly who is the most apt to compensate for those.

Also, one of the most reliable allies of the Mongol army commanders was intelligence. During the Black Sea campaigns, the Mongols gained precious information from traders (mostly Venetian) on European geography, armies, castles, population, the relations between rulers, supplies, and everything else useful on a campaign. Therefore, when they invaded Eastern and Central Europe in 1241/42, they knew exactly where to go, what to do, whom to attack or avoid, what the most vulnerable points were. The result was that they crushed several very strong European armies, pillaged several countries, and made them pay tribute.

Q7. What were, in general, the most fruitful areas of influence, where we can observe overwhelming changes? Was it in transportation, in weapons, communication, knowledge management, construction, energy, medicine, economy? And can we single out one or two dominant areas?

The Romans had exquisite mastery of construction: just take a look at their buildings all around the Mediterranean basin and beyond. It was as late as the early 20th century when the construction improved significantly. For example, the formula for Roman concrete is still sought for: its durability, resilience to saltwater, and longevity have not been surpassed to this day. All major civilizations were aware of the importance of roads and communication. On the other hand, the concept of economy is quite complex: even the best experts have troubles predicting many aspects of its development.

I could single out the change that happened to humankind with the invention of electricity. Also, the Internet contributed to unimaginable access to all sorts of information and dissemination of knowledge. Last, but certainly not the least, medical advancements need to be mentioned. Ancient civilizations had quite capable physicians. I remember a note from Greek historian Herodotus (5th ct. BC) in which he gives an account, and was quite surprised, that the Egyptians had doctors who were specialized for eyes, internal organs, etc. – just as we have today. The Chinese have had quite rich tradition in medicine as well. But what the field has achieved so far, with personalized medicine and with all the technology at our disposal, is just to become even more impressive. After all, the fear of non-existing (even of just being ill) is one of the most potent incentives known to humankind.

Q8. Today we have polarization between the USA and China, and the EU in some segments regarding technology innovations. Was there a country that was famous as a technology leader or an expert in one field?

Throughout its rich history, China was well-known for its innovations. The compass (12th ct.) made the oceans a less hostile environment, the paper money (11th ct.) made the trade and financial transactions easier, while the invention of gunpowder (11 ct.) changed the warfare of the second millennium AD. Of course, it is only through the transfer of knowledge in the late Middle Ages that most of these inventions got improved – e.g. the Venetian and Genoese merchants made significant strides to advance the financial instruments invented either by the Chinese or by the merchants in the Islamic world; gunpowder-based weaponry, such as cannons and rifles, were also improved across Eurasian continent.

In ancient times the civilization that lived in Mesopotamia was famous for its inventions. We have mentioned some: the wheel, cities, writing. However, there were dozens more, such as administration, accounting, mathematics, astronomy, sailing, production of bricks, cartography, and maybe the most interesting one: the concept of time. Based on their sexagesimal system, our hours have 60 minutes which are subdivided in 60-second intervals.

Q9. Most importantly, what can we learn from those who missed opportunities and didn’t advance on time? Which civilizations collapsed or became irrelevant? What can we advise modern states, and warn them if they miss current opportunities in AI development, genetics, or any new technology that will emerge soon? Our time to react is getting shorter, and the consequences are getting bigger.

The rise and fall of civilizations were in focus of historians for many centuries. They happened mostly as a combination of several factors: ecological, economic, social, technological, richness or depletion of crucial resources such as timber, oil, or ore deposits. The system of nation-states is arguably the invention of the 19th century, and it is the best humankind has available for the moment.

One can conquer a land with a military machine, but one of the things that might have changed the world, even more, is a relatively simple invention: private property. Indigenous peoples of Australia, the Americas or Africa, who considered themselves guardians of the land they lived on, were deprived of the space they took care of. It certainly was one of the game-changers in the evolution of humankind. History gives many examples of those who were not resilient enough, not sufficiently developed or just different in terms of economy, social organisation, or technology; in the end, they no longer exist. Or at least, their way of life no longer exists. Does that mean we need to be constantly alert and improve so we do not get surpassed by rivals, or should we redefine our existence altogether? This is our dilemma. (Certainly, for a long period of history we needed the former.)

The proper globalization that started in the 20th century has demonstrated how entangled all the aforementioned factors can be. We have all witnessed what small yet provident nations such as Singapore or Norway are capable of. We are all witnessing how China has managed to multiply its industrial and financial output although it seemed that technologically it was quite behind some superpowers in the domain, only a few decades ago.

In the 21st century technological advancements in biomedicine, nanotechnology, rocketry, the AI (…) will enable people to create fabulous things. Already now pretty much anything can be produced; it is just a matter of how much money and effort is invested. There are two key questions: ‘What are we interested in?’ and ‘Who are we?’ And here I refer to a nation-state, a multinational corporation, an elite of some kind, a group of conscious individuals. As ever, it will be a combination of factors, but it seems that the least problem will be inventions of new technologies. There will be new battlegrounds of the political, social, and ethical challenges trying to answer the questions how to use the technology, and how accessible it will be.

Finally, I believe you are painfully right about the reaction time, the pressures, and the consequences. Most of us receive in one day the amount of information a single person in the Renaissance (just 15 generations ago) received during their lifetime. Shall we succumb to all sorts of internal and environmental pressures? The paradox is that humans can be very fragile, yet highly resilient. With everything happening so fast and with so much at stake, we all need to learn new things, learn more, and, as ever, adapt to crucial changes in our environment.

More interviews with Mirko by Aco on TCN:

Mirko Sardelic PhD: A Brief History of the Most Devastating Earthquakes

Mirko Sardelic PhD Interview: History of Pandemics: Lessons to Apply to Corona Crisis

You can read more from Aco on his Medium profile.