I have had a LOT of reaction to my blogs (and now vlogs) over the last 11 years since I started writing about Croatia, but I can’t recall anything quite like this.

I recently started a YouTube channel called Paul Bradbury Croatia & Balkans Expert, a place where I am looking at life here over the last 20 years, and I have been stunned at the level of interest and engagement. The first 1000 subscribers (needed for monetisation) came after just 11 videos, and I have been enjoying interacting with my growing audience. It is the start of what could be quite a fun journey. If you want to subscribe to the channel, you can do so here.

One of the more popular videos has been this one above, 25 Most Common Mistakes Croats Make Speaking English. It was great to get so many messages from Croatians saying that they had learned something from the video (you are welcome), as well as the inevitable trolls demanding to know why I don’t speak Croatian after 20 years here (hrvatski je svjetski jezik kojim govore samo najpametniji ljudi. Nisam toliko pametan, trudim se). On one of the comments, I for one would be keen to come across a similar article pointing out common mistakes foreigners make in Croatian.

And then, last night, I received this…

Hi Mr. Paul,

I don’t even know how to start this email. So, let’s just cut to the chase.

I recently came across your video on the 25 Most Common Mistakes Croats Make Speaking English. I liked it a lot. I found it intuitive and decided to accept your challenge in my somewhat perky way.

Why? I love writing. I love the Croatian language and orthography. I work as a freelance translator (and proofreader and content writer etc.), mostly for Booking.com, and I am experiencing a phase of decreased number of projects at the moment so I finally got time to write something that truly makes me happy. Also, I know my English is far from perfect, so I usually avoid writing in English. This is me leaving my comfort zone (big time).

I am sending you this as a sign of appreciation and acknowledgment of your video. But also to thank you for what you’re doing for the promotion of our country and for fighting our mutual ‘enemy’:the National Tourist Board. This is actually what brought me to you and Total Croatia News. That requires some really steady nerves (the uhljeb story, I mean). Respect. Hope I will be able to get to your Nirvana stage someday soon. 🙂

In conclusion, please find attached ‘the novel’, I mean my article: Challenge accepted: let’s talk the horrors of Croatian language. I do not expect you to publish it. You can just read it, since I am under the impression you value these things. If you do want to publish it, I will not mind. However, it is going to need some good editing (and cutting probably). Mother tongue interference is strong with this one.

Anyhow, I hope it will be at least somewhat useful to you, as was your video to many Croats and me personally.

Apologies for the length of the document. I just do not know when to shut up.

Kind regards,

Anamarija

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED: LET’S TALK HORRORS OF THE CROATIAN LANGUAGE

Recently I came across a YouTube video by Paul Bradbury, whom I basically know for sharing probably the same ”passion” towards the Croatian National Tourist Board as I do. The video was related to language matters, not the legal and uhljeb ones. To cut a long story short, I really appreciate what he is doing for Croatia and its tourism, so I accepted his challenge and decided to write a piece on 20 mistakes non-native speakers (and not only them) make when speaking Croatian. To be quite honest, probably 90% of the listed mistakes are made by the majority of Croatians too. Anglicisms and pseudo-anglicisms are all the rage nowadays, but that is a completely different story. As Paul put it: if you know English, you’ll do well in Croatia. Don’t you ever get discouraged by something as padeži? These are not worthy of your tears.

Paul is so much more hip than I am, and he made a video. I did not make a video. Firstly because – as many others do – I hate the sound of my own voice on audio and video recordings. Secondly, I’m an old-fashioned girl. If I can make someone read in this day and age, I will do it. And I make no apologies.

Croatian is widely considered one of the hardest languages to learn for English speakers, right after Mandarin and the languages of Finno-Ugric language group. Speakers of the latter language group struggle with an even greater number of grammatical cases than we do. Imagine that horror!

Here are some practical language tips on how to excel in Croatian and avoid some common mistakes. So common that a significant percentage of Croatian people aren’t aware of making those mistakes either.

1. Shall we start with light and trendy topics? Let’s talk about THE beverage: pivo/beer!

So is it piva or is it pivo? The only correct form is pivo. I can understand how fond some men are of both beer and female gender so they use every possible occasion to draw comparisons between these two, even if only by playing with grammar matters. However, grammatical gender is something you cannot change, not even in the 21st century. Pivo is of neuter gender, not the female one (piva) and that is a fact. To all the men out there: you are no less a man if you address it in the neuter gender.

2. The right to enjoy one’s beer in peace can be considered a matter of human rights, don’t you agree? Well, among non-native speakers, human rights are often translated in Croatian as čovječja prava. Hard to believe it since you literally need to break your tongue to pronounce it, huh? This is, however, a literal translation from English. The only correct form in Croatian is ljudska prava (derived from the noun ljudi = people).

3. When someone buys you a beer, it is appropriate to thank him/her. So, you’ll probably say something like hvala lijepo….And that is awfully polite of you, but is not correct in Croatian. You should always say hvala lijepa (because hvala is of female grammatical gender).

4. Let’s stick to means of expressing our gratitude for a little while. This one is hard to grasp, even for Croatians. It makes all the difference in the world whether you will zahvaliti or zahvaliti se. E.g. When someone offers you a gift, there are two possible scenarios, and in both, you can use either zahvaliti or zahvaliti se. When you decide to accept the gift and express your gratitude, you will most likely say something as: zahvaljujem, divno od tebe/thank you, that is so lovely of you. However, if you decide to politely decline it, you will most probably say: zahvaljujem se, ali ne mogu to primiti/ thank you, but I cannot accept it. Also, when you’re firing someone, and you want to gently deliver the news, but you don’t have a cute niece around you to sing a Frozen tune along (bad joke, I know), you will use the following wording: nažalost, moram vam se zahvaliti/ I regret to inform you…

5. Now on homographs and homophones and context (they have nothing to do with your sexual orientation… or they might, who knows). So what does it really mean kako da ne? Does it mean yes, of course or the hell no? Knowing the difference makes all the difference. But the trick is: it can mean both. I can understand how people get lost in translation so easily with this one. The trick is to pay attention, depict the pitch of the voice and observe the face. If you have a Grouchy Smurf in front of you, it’s probably a hell no. If you get a smiley face, or even doubled kako da ne, kako da ne, you got yourself a definite yes, sir/madam.

6. And now to make things complicated. Padeži give us hell. I know. But, one of the seven musketeers is especially avoided amongst non-native speakers of Croatian, and it is an instant traitor. It’s the vocative. It’s wrong to say: Ej, Ivan!/Hey, Ivan or Ivan, dođi ovamo/ Ivan, come over here. Instead, you should say: ej, Ivane and Ivane, dođi ovamo. Vocative asks for a suffix. There are exceptions, however. Of course, there are. Those exceptions are names such as Ines, Nives, Karmen etc.

In this article, I am discussing mainly spoken language, but there is one other distinction in written language when speaking of vocative: it always comes separated with a comma.

7. To stick to names, let us discuss possessive adjectives. This is a huge mother tongue interference from English. One should never say prijatelj od Stipe. You say Stipin prijatelj/ friend of Stipe. Using the preposition od + genitive form is not in accordance with Standard Croatian. Thus, you should always use a possessive adjective instead.

8. How about svoj versus moj? In Croatian, belonging to a subject is expressed through the possessive-reflexive pronoun svoj, roughly translated as one’s own. Some call it a super possessive pronoun. That’s how we roll in Croatia. So, if you want to say: I am going to my apartment, the wrong way to put it would be Idem u moj stan (although moj means my). Instead, say: idem u svoj stan.

This is an extremely common mistake even amongst native speakers, so don’t get discouraged if it takes time for you to develop natural language processing.

9. English loves the passive voice. However, Croatian not so much. Why is that so? Probably because we like to be acknowledged, involved and informed of who did what #MiHrvati. Thus, in English it is normal to say the complaint was made by the employees, but it is not natural to say podnesena je žalba od strane zaposlenika (which you can hear a lot in administrative language amongst uhljebs). Instead, say: zaposlenici su podnijeli žalbu. Just not to make us rack our brains over who did what. Work smart, not hard (what an irony).

10. Okus and ukus. I know! You have to pucker up your lips out there to pronounce it just to end up looking like a fish and ultimately find out you opted for the wrong one. But, it is as simple as it gets. Yet, it gets interchanged way too often. Okus is used when referring to flavour and ukus denotes taste, as in a person’s implicit set of preferences. You have good taste = imaš dobar ukus. Saying to someone imaš dobar okus would imply you’re a bit more than friends.

11. Changing the subject. So, which team are you: team more or team voda? Have you already found yourself in a situation where you almost felt verbally assaulted by a Dalmatian explaining it to you: it’s not water, it’s the sea. Potato potato if you asked me. From a linguistic and scientific point of view, you are not wrong. Seawater is still water, just not the drinking type. But sometimes you cannot rationalise things with the people of Dalmatia. So, how to proceed with this one? However you want. This is ‘the mistake’ that is actually not a mistake per se. It is a battle you cannot win. I gave up fighting a long time ago (don’t tell anyone, I have Herzegovinian roots, so I have no right to vote on this one). Yet, I boldly go where only Herzegovinians and the good folks of diaspora have gone before and I get to choose. Sometimes I enter the water, sometimes I enter the sea.

12. Let us shortly get back to grammatical cases again. Of all the cases in Croatian, instrumental is probably the easiest and most logical to learn amongst non-native speakers. However, there is something where most of them stumble. To preposition or not? It should be easy: 1) when instrumental is used in the context of explaining a tool or the means used to accomplish an action, you must leave out the preposition; 2) when talking about company and the unity of 2 entities, you will most definitely need a preposition. Thus: pišem olovkom/ pišem s olovkom (I am writing with a pencil), putujem autobusom/ putujem s autobusom (I am traveling by bus) BUT Putujem s Barbarom (I am traveling with Barbara) and volim palačinke sa sladoledom (I like crepes with ice cream).

13. Vi ste došla. Croatian is already complicated enough, so let’s not complicate things where they are quite so simple. When addressing someone informally you need to pay attention to grammatical gender. However, this is not the case when using the formal Vi form. The ending is always the same both for female and male grammatical gender. Gospodine Smith, vi ste došli/ Gospodine Smith, vi ste došao. Gospođo Smith, vi ste došli. Gospođo Smith, vi ste došla.

14. Ukoliko/ako = if: you shall not break your tongue in vain! Save your breath. First, I hear you on how hard it is to pronounce ukoliko. Good news is: it’s a common mistake to misuse ako and ukoliko among native speakers as well. The secret to forcing usage of ukoliko lies in the fact it sounds more erudite. However, ukoliko must be used only in combination with utoliko. In all other cases, you should use ako. They practically mean the same thing. Ukoliko ti plaćaš, utoliko idemo na kavu. Ako ti plaćaš, idemo na kavu. If you’re paying, we’ll have coffee. To conclude: when in doubt, use ako.

15. The next point is strictly a spelling matter. There is a distinctive difference between writing down numbers in Croatian and in English. There is no such thing in Croatian as a decimal point (used to separate a whole number from the fractional part of the number). Instead, we use a decimal comma. Thus 67.8 EUR or 67,8 eura. When it comes to small amounts, it does not seem like a big deal. However, when talking big money, it can make all the difference in the world. Write wisely.

16. When it is not padeži time, it is glasovne promjene time. Both can be summed up as headache times. But there are things you just have to learn and learning is a long and painful process.

- Sibilarizacija, known as Slavic second palatalization, is the sound change where k, g and h when found before i develop into c, z, s.

Why is this important to us? Because this is the reason why it is wrong to say u ruki mi je, instead of u ruci mi je (it is in my hand).

- Slavic second palatalization is a sound change where k, g h when found before e develop into č, ž, š.

In practical usage, it means it is wrong to say hej, momak/ hey, boy. Do not get fooled by the Dalmatian dialect where you probably hear ej, momak a lot. This is due to the fjaka state of mind. Everything is a bother, even using sound changes. Instead, steal the show and say hej, momče.

17. I know this is already a lost battle, but I am using every possible occasion to beg you: please, do not use the term event when speaking Croatian. If Croatians want to sound important, let them be. However, the original Croatian word for the megapopular event is događaj or događanje. I know it is painful to pronounce it, but I want you to know that for each time you use the term događaj instead of event, someone on this side of the screen will love you more. In case of public writing, the love doubles. Cross my heart and hope to die.

18. It’s Christmas time. It’s welcome parties time. Many are heading to the capital of Croatia these days. In colloquial language, it is popular to say idem za Zagreb (I am going to Zagreb). However, this is wrong. You should always say: idem u Zagreb. Motion verbs ask for the preposition u instead of the preposition za (preposition u > preposition za).

19. I know the Italian language sounds more romantic, but when you order prosecco in Croatia – you get bubbles. If you want to try an indigenous product, ask for prošek. Many confuse Prosek with Prosecco due to a lost in translation moment. However, the difference is major. Prošek is a thick and syrupy still dessert wine. Thus, do not worry about translation and the labels of the protected designations of origin and just taste it. Enjoy the simplicity.

20. Ah, I saved the last dance for you. There is a popular opinion that the usage of particle/conjunction groups da li and je li is a matter of major distinction between the Croatian and Serbian languages. This is not necessarily the case. However, the usage of the group da li is not in accordance with the normative rule of Standard Croatian. Thus, to form an interrogative sentence, you should opt for verb + particle li (commonly known as je li group) instead of da li. E.g. Da li je to restoran o kojem si mi pričao? Je li to restoran o kojem si mi pričao. However: Da li me voliš? Voliš li me?

You have my respect If you managed to reach the end of the article. Go reward yourself with one pivo now. All jokes aside, Croatian has many dialects and sub-dialects. Many non-native speakers learn the language from online sources created by Croats in the diaspora (where the majority did not learn Standard Croatian) or from locals using the dialect. There you have a root for all the above-mentioned mistakes.

Also, the trait of the Croatian language is that it is rather liberal, more descriptive than prescriptive in nature. For this reason, it does not have one official orthography. Instead, there are many unofficial editions. However, the recommendation is to choose one and aim at consistency.

For all that has been said, do not ever get discouraged by making mistakes. We all make them. Bear in mind one significant difference: it is easier to learn English nowadays with all the variety of learning tools and sources out there. To learn Croatian as a non-native speaker is a true stunt. An admirable one. Do not give up.

****

Wow, thanks Anamaija – I certainly learned a few things (and am still recovering from someone writing a 3,000 word response to one of my videos). I asked Anamarija to tell me a little about her. If you want to contact her, let me know on [email protected] and I will pass on your details.

My name is Anamarija (full name: Anamarija Pandža) and I live in Omiš, the stunning small town I am incurably sentimental about.

I am 50% English to Croatian human translator/ court interpreter/ proofreader/ content writer/ entrepreneur and 50% coffee. Coffee and the sea are the only 2 things I cannot live without. That is, I can – but I choose not to. I’m also a huge fan of words. They are my playground. I use quite a lot of them, both for making a living and to rant for the sake of ranting.

You will find me at the kids table. Always. Utopist. Forever smiling Grouchy Smurf. Forever waiting for a Godot. Also, forever a black sheep wherever I go. In love and hate relationship with this country and its people.

The worst and the best thing you can do is to tell me to give up. That is when the game begins. I never give up. This is why I chose not to give up on Croatia either.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning – Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Subscribe to the Paul Bradbury Croatia & Balkan Expert YouTube channel.

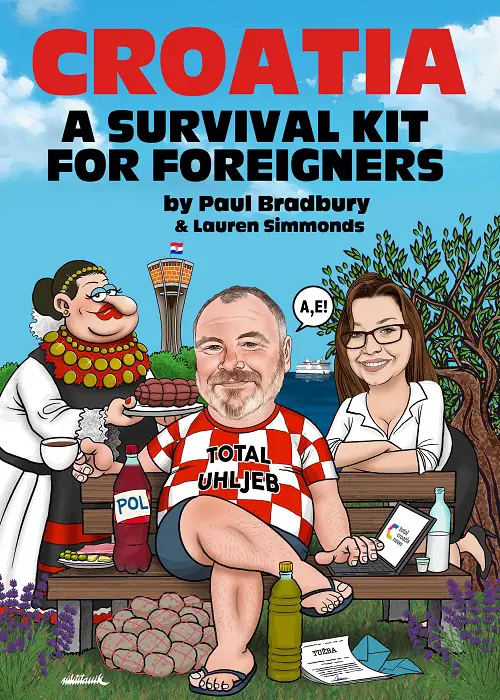

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.