After the Petrinja earthquake last week, TCN visited Petrinja, Sisak, Glina and Majske Poljane to try and paint a picture of the realities on the ground of the destruction and emergency response. You can read more in Majske Poljane, Glina, Petrinja: A Foreigner View of Croatia’s Emergency Response (there is also a Croatian version).

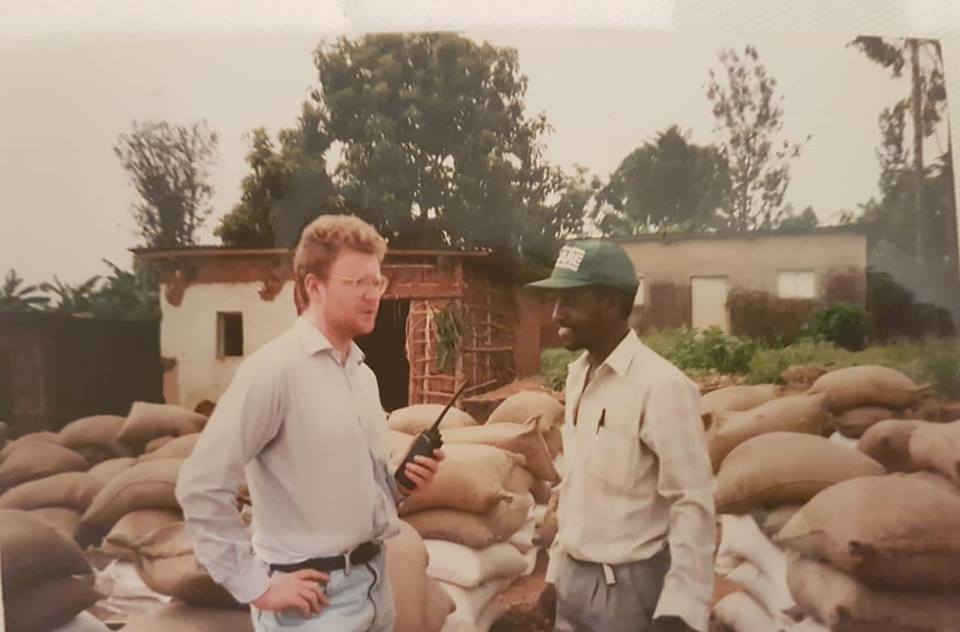

I was subsequently contacted by the Croatian media for an interview about the earthquake response in my capacity as a former emergency humanitarian aid worker. Before moving to Croatia in 2003, I worked as an aid worker for CARE International in emergency response in the Ural Mountains, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992, Rwanda after the 1994 genocide, and Somalia in 2002.

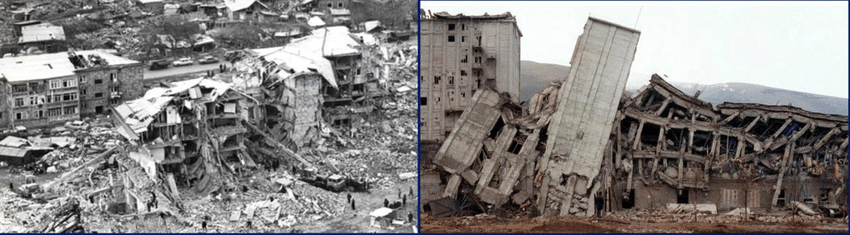

You can see the original article in Croatian here, and the full interview is in English below. Please be warned that if you decide to watch the video on the Armenian earthquake in 1988, which killed 25,000 people, it is harrowing.

You’ve visited the area that was hit by the earthquake. What are your general impressions? Is it as bad as it looks?

I think earthquake sites are always worse than they look, as many of the buildings may still be standing and looking relatively unharmed from the outside, but are actually inhabitable.

I have never covered an earthquake as a journalist before and was not sure where to start. We decided to leave very early (5am), so as not to add to any traffic congestion. We decided to start in Majske Poljane, which we had heard was the most affected place. It was horrendous, with every building affected, many completely destroyed. One always gets only part of the story on the ground. It was only later that I learned that the destroyed house with 10 bewildered horses that was our first stop was the home where four people tragically died.

After such a shocking introduction, Glina and Petrinja seemed – on the surface – to be a lot less damaged. But as I said earlier, much of the real damage is not available to the naked eye. Some official compared it to the ruins of Hiroshima, which I don’t think was very helpful. That impression is also due to the outstanding clean-up operation which took place through the night. A friend in Petrinja showed me photos he had taken soon after the earthquake 24 hours earlier – it was a totally different place. My full respect to all who responded so quickly and magnificently.

(Gyumri in Armenia after the 1988 earthquake)

The biggest earthquake site I visited as an aid worker was Gyumri in Armenia, a 7.0 quake which killed 25,000 people in 1988. Gorbachev promised to rebuild everything, but soon the Soviet Union was no more, and we were delivering humanitarian aid to people living in containers 5 years later. While I don’t expect anything like the same situation in Petrinja, Glina and Sisak, it would be heartening to know that the region will not be forgotten once all the initial media attention and emergency response dies down, as it was in 1995.

As a former aid worker, can you tell me from your experience what is the most important thing if you want to help people that were hit by some kind of catastrophe?

Organisation over emotion. I should say, however, that I don’t think Croatia has many lessons to learn from foreigners, or former aid workers like me. Croatia’s emergency response is second to none, and there is no nation stronger in adversity than Croatia.

But the question of organisation is key. The overwhelming urge is to get in the car and bring food and supplies to help. Without coordination, this can quickly congest the system, as well as neglecting lesser-known areas. Croatia has experts in emergency response. We interviewed HGSS chief Josip Granic while in Petrinja and asked what advice he had for those looking to volunteer. His response was to contact the local Civil Protection Headquarters, which is sound advice.

I should point out that sometimes it is important to pay attention to the type of aid being sent. While cash donations are most welcome, sending materials randomly is not always helpful. Not only can it take up storage space and valuable time documenting and storing them, but they may also not be of any use. Perhaps the most extreme example I can give from my personal experience was after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, where my project received 20 tons of vegetable seed from an American seed company. This was enough to cover large parts of Africa, and it turned out to be a tax write-off from the company. But it really slowed things down, as the 1.5 million sachets of seeds in the container had no description. As an accountable agency, I had to hire 20 local workers for three weeks to document the gift. It was particularly disappointing to find we had received a lot of useless things, such as 8,000 sachets of catnip seeds.

I haven’t followed the response in detail in terms of aid being distributed, but a survival pack work worth 200 kuna, 400 kuna etc with a list of essential items would make things more uniform, and people would know the items most required.

Should the delivery of humanitarian aid be centralized?

Yes, absolutely. In Rwanda, a country the size of Wales, we had 143 NGOs roaming all over the country in their white 4x4s, some with bibles, some with food, many with agendas.

Croatia SHOULD be no different, but there is always the sub-plot here called politics. I have a sinking feeling once more after witnessing such a magnificent early response from the heart. Now the recriminations, accusations and distrust are setting in. You and your readers will know more about that than I do.

The reality is, however, that the response shows one of the big divides in Croatia today. Distrust of the state, lots of heartwarming private initiatives. Back in my aid worker days, it would have been unthinkable to bring the reputation of the Red Cross into question, but there has been plenty on Index and elsewhere on that subject. Lots of foreigners have asked me where to donate. I am recommending the guys at Glas Poduzetnika. Not only are they honest and transparent, but they are big enough and experienced enough to work within the emergency response system for maximum effect.

What’s the problem with the response of the Croatian local and state authorities in this situation? Why is everything moving so slowly but at the same time chaotically?

I am not as informed on the details of this, and so perhaps best for me to leave it to others to comment.

On the other hand, lots of citizens and groups have been doing great work in helping those hit by the earthquake. Is there a way to coordinate those efforts better?

It comes back to organisation over emotion above. Coordination can always be better, and Croatia has lots of experience in this field. It would, I believe, be even better if there was more trust in the authorities. I would suggest that people put their natural desire to provide hands-on help in check and find out what the most practical way to help would be.

One of the bigger problems is traffic. Should there be some kind of timetable for using the roads that survived the earthquake?

I was actually surprised at how little traffic there was when we visited the day after. We left very early to avoid it, but the police seemed to have managed things very well. There were a couple of checkpoints around Petrinja. We were allowed to proceed with a press pass. Controlling the traffic is something Croatia does very well. I will never forget how effectively we were confined to our home towns in March – scary but very effective.

For the latest news from the Petrinja earthquake, visit the dedicated TCN section.

If you would like to donate to the earthquake relief efforts, my recommendation is Glas Poduzetnika (Voice of Entrepreneurs) fund – full details here.