In 2007, an initiative was launched in Zagreb to erect a monument to Andrija Mohorovičić, a world-renowned geophysicist and founder of modern seismology. It’s been a minute, but the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts has finally announced that the project will be implemented in the capital city this year to mark the 165th anniversary of the birth of the researcher (HINA).

As we’re waiting for one of the greatest minds of Croatian science to get a tribute he deserves, let’s look at his life and career before another 15 years go by. Who was this great man and what is his legacy?

Mohorovičić was born in 1857 in the small Croatian town of Volosko (near Opatija) and finished secondary school in Rijeka. He was a talented pupil from an early age and spoke fluent Italian, French and English by the time he was 15; he’d go on to learn Latin, Ancient Greek, Czech and German later on.

Childhood home of A. Mohorovičić in Volosko

He studied mathematics and physics in Prague, then went on to teach high school in Zagreb, Osijek, and at the Royal Nautical School in Bakar (near Rijeka). This was a turning point in his scientific career, as that’s where he developed a strong interest in meteorology and established a weather station in Bakar as a result.

In the 1890s, he requested a transfer to Zagreb where he soon took over the reins of the Meteorological Observatory, all the while teaching courses on geophysics and astronomy at Zagreb University. What equipment he didn’t have, he designed and built on his own, such as a nephoscope, an instrument for observation of clouds he used to collect readings for his doctoral dissertation.

Mohorovičić was the first person to establish a public time service and also the first to publish weather forecasts in newspapers. He’s remembered as a meticulous researcher who unified the weather service in Croatia and set high standards for further development of meteorology.

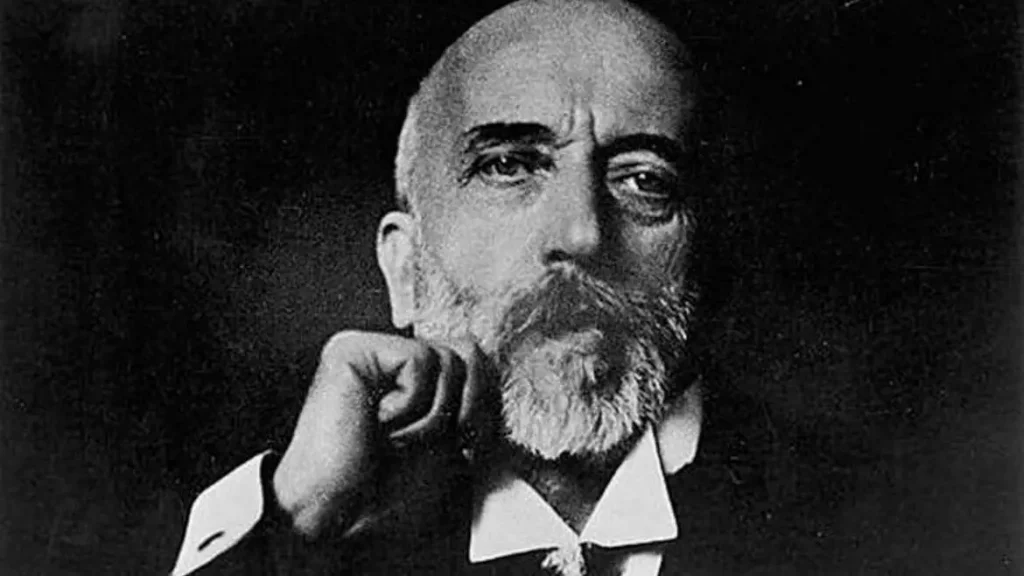

Portrait of Mohorovičić in Opatija

And then, another turning point at the beginning of the 20th century. Even though he continued to consistently record meteorological observations, Mohorovičić shifted his interest to seismology and essentially started from scratch where his career was considered, as this particular field was not much developed in Croatia at the time.

It’s not really known what inspired the scientist to turn to a completely new field of research, but it’s believed it was the lively seismic activity around Zagreb that piqued his interest. Mohorovičić installed the first seismograph at the Meteorological observatory in Zagreb, effectively founding a seismological station in 1906.

He soon replaced the instrument with two more advanced seismographs, which he would use to record data during the Kupa Valley earthquake in 1909.

Those readings, together with others recorded all over Europe, led to his biggest scientific discovery: the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or Moho for short, the boundary between the Earth’s crust and the mantle. The same boundary on Mars and the Earth’s Moon also bear his name.

Having studied the effect of seismic activity on buildings, Mohorovičić was also a strong advocate of earthquake-resistant construction. He held a series of lectures at the Croatian Society of Engineers and Architects starting from 1909, in which he set out to explain ‘how the Earth trembles, and how these tremors affect buildings, and draw attention to some principles that both architects and building contractors should follow’.

Quite a straightforward concept today, but a groundbreaking approach in the early 20th century, especially given that he urged developers to ‘consider the earthquake hazard and spend more, in order to make buildings more resistant and safe’. Over 100 years later, we still haven’t learned our lesson.

Mohorovičić was truly a man ahead of his time, a visionary and a scientific pioneer in many ways. He was one of the few Croatian scientists of international renown to remain based in their homeland for their entire career; he taught at university level, published papers and remained a member of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts until he retired in 1921.

Owing to his greatest discovery, a crater on the far side of the Moon bears his name, as well as an asteroid, a secondary school in Rijeka, and a training ship of the Croatian Navy.

This article is mainly based on an essay written by Davorka Herak and Marijan Herak of the Andrija Mohorovičić Geophysical Institute.