July 17, 2020 – Zagreb’s residents have voiced outrage at the removal of a beloved work of art, replaced by nothing. But is this really anything new for Croatia Public Art?

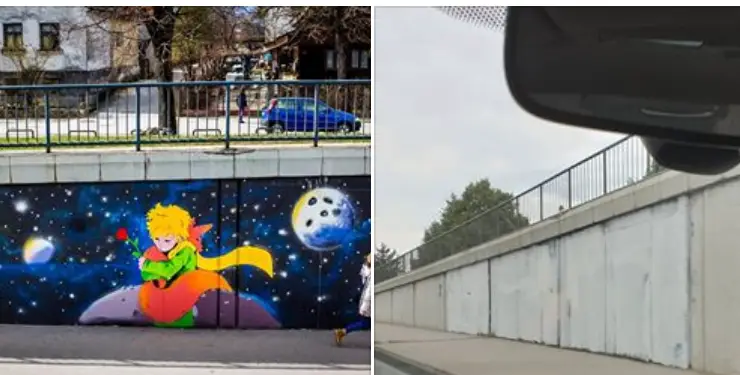

Over the last 24 hours, residents of Zagreb have voiced their outrage at the removal of one of the city’s best-loved pieces of street art. ‘The Little Prince’ had sat in Čulinečka ulica in the Dubrava neighbourhood since 2016. But now it is no more.

Inspired by French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s novel – one of the world’s best-selling and most-translated books – the mural was placed at the end of a busy underpass. As such, it was a colourful piece of Croatia Public Art, a welcome for motorists entering the drab, grey concrete of the city, stuck in traffic, on their way to another grueling day of work.

Updates to the story have revealed the culprits to be fans of the local football team, Dinamo Zagreb. They had been given permission to paint yet more murals of their logos and slogans on the rest of the underpass, under the provision – according to neighbourhood authorities who granted it – they did not touch the existing artwork. But they did. Where once was placed an inspiring and cheering mural, there now sits nothing.

Representatives of the largest organised group of Dinamo supporters – known as Bad Blue Boys – have, at the time of writing, failed to comment on the affair. Perhaps they weren’t aware of the Dubrava sect’s actions? They certainly don’t appear capable of reprimanding their own members. So much for claiming to be ‘organised’. Or perhaps they’re just exhausted by all the bad press?

In recent memory, the Bad Blue Boys have repeatedly hit the headlines and, to be fair, not always for such reprehensible, thoughtless behaviour. Following Zagreb’s 2020 earthquake, supporters came together as some of the first responders at the scene of a hospital, where they assisted in removing infants from the damaged wards. Bravo! But, then young supporters were pictured with a banner bearing the scandalous words “We will f*ck Serbian women and children”

Representatives from the Bad Blue Boys were quick to denounce the disgusting banner. Bravo! However, they implied the wording was only problematic as it pertained to pedophilia. Eek. And, within 24 hours, the same voices were raging about anti-Croat slogans used by Serbian football fans, in that classically Balkan method of argument where you ignore the issue at hand, point somewhere else and say “But, they are much worse!”

With the removal of ‘The Little Prince’, this time they seem to have gone too far. All but the most insecure and ardent of supporters have turned on the Bad Blue Boys, labelling them hooligans, idiots and selfish. Comments under news items covering the story are filled with angry criticism for the football fans.

“They like to paint themselves as hooligans who we should all fear,” one angry Zagreb resident who wished to remain anonymous, told TCN, “but really they can only paint their retarded logos. They piss all over the city like feral dogs marking their territory. Their murals are already on walls everywhere, why destroy this art? Everyone loved it! They are not even real football fans, let alone hooligans. They boycotted (attending) because of the club’s (allegedly) corrupt management, but as soon as the club released 1 Euro tickets, stadium was again full. For 20 years they shout and spray (paint) fake anger over corruption at the club, but they don’t do a thing about it. The same people are still in charge and the stadium is full of these so-called fans. Can you imagine that happening in a football club in your country, in Spain, in Argentina, in Brazil? No. Impossible. Such corruption would not last a year before fans removed them. The corrupt would be assassinated if that’s what is needed (to remove them). They are not Bad Blue Boys, they are Big Blue Babies. They are dogs with loud voice but absolutely no teeth”

The anger of Zagreb residents is palpable. But, can we blame the pointless and saddening idiocy of this affair on the Bad Blue Boys? Like the disgusting slogan on the teenage supporters’ banner, such rhetoric does not appear out of thin air. Actions like these are sadly learned. And the country has an established history of needlessly destroying Croatia Public Art and replacing it with… nothing.

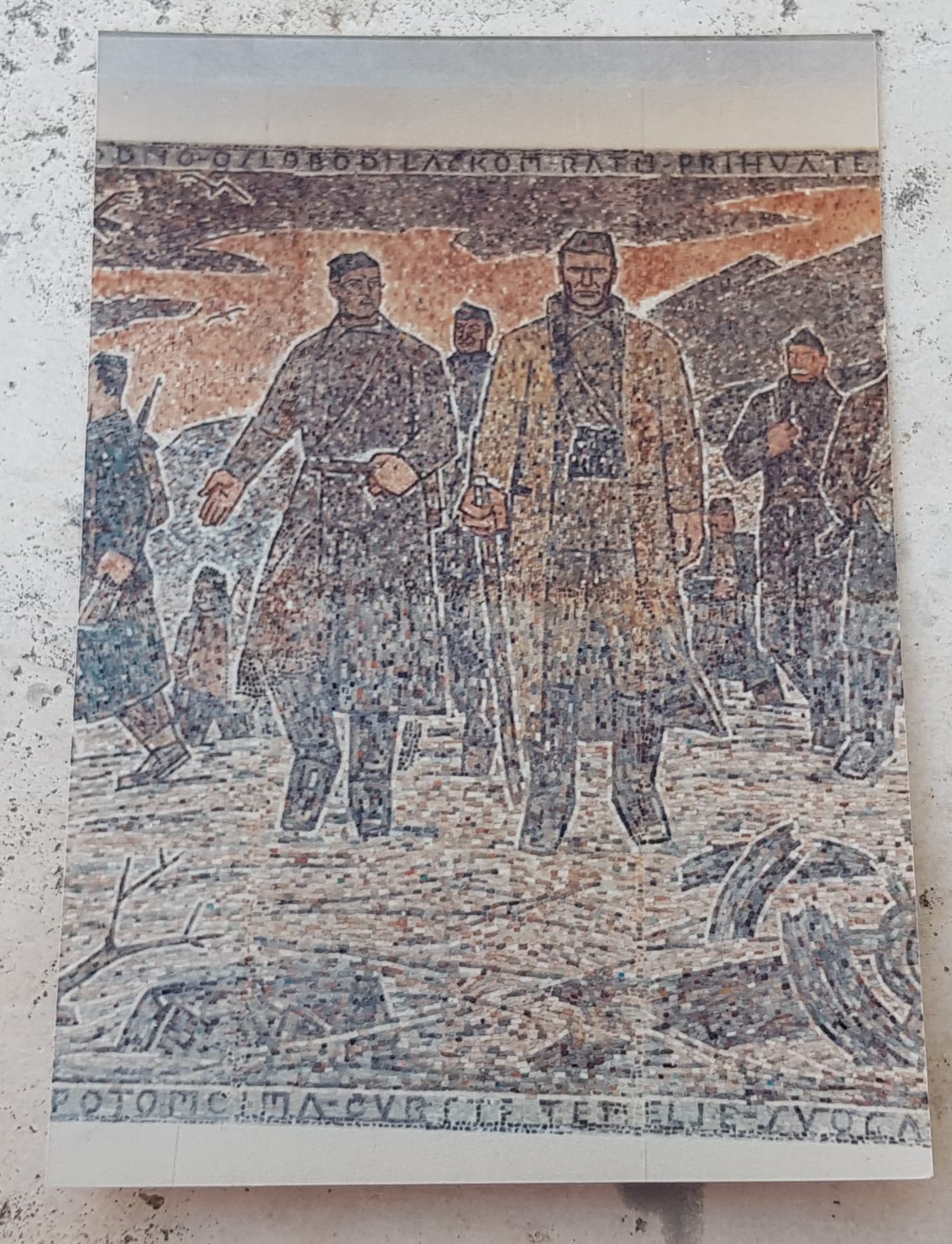

A photograph of a small section of Ivan Joko Knežević’s mosaic in Omiš, the only record in colour remaining of this piece of Croatia Public Art © Knežević family archives

The long-cursed bottleneck on the Jadranska magistrala (Adriatic highway), the Dalmatian town of Omiš, is now fighting to attract the kind of footfall that its neighbours Makarska and Split experience during summer. And, sitting at the mouth of the Cetina river, it sure does have a lot to offer. However, one thing it no longer has to offer is the amazing mosaic created by renowned local artist Ivan Joko Knežević on one of the town’s most prominent squares. Today, the square is known as Trg Franje Tuđmana (but, of course it is – it’s probably very close to a street called Ante Starčevića too) and where the beautiful mosaic once stood, there sits a blank wall. This piece of Croatia Public Art was removed under a wave of nationalist sentiment following Croatia’s war of independence, solely because one of the local scenes it contained depicted Partizan soldiers (who fought to recapture for its inhabitants this very area from the Nazi-allied Italians it had been gifted to). Now, there is no reason for tourists to come to this square other than the drinks on offer. They sit and sip and look at nothing.

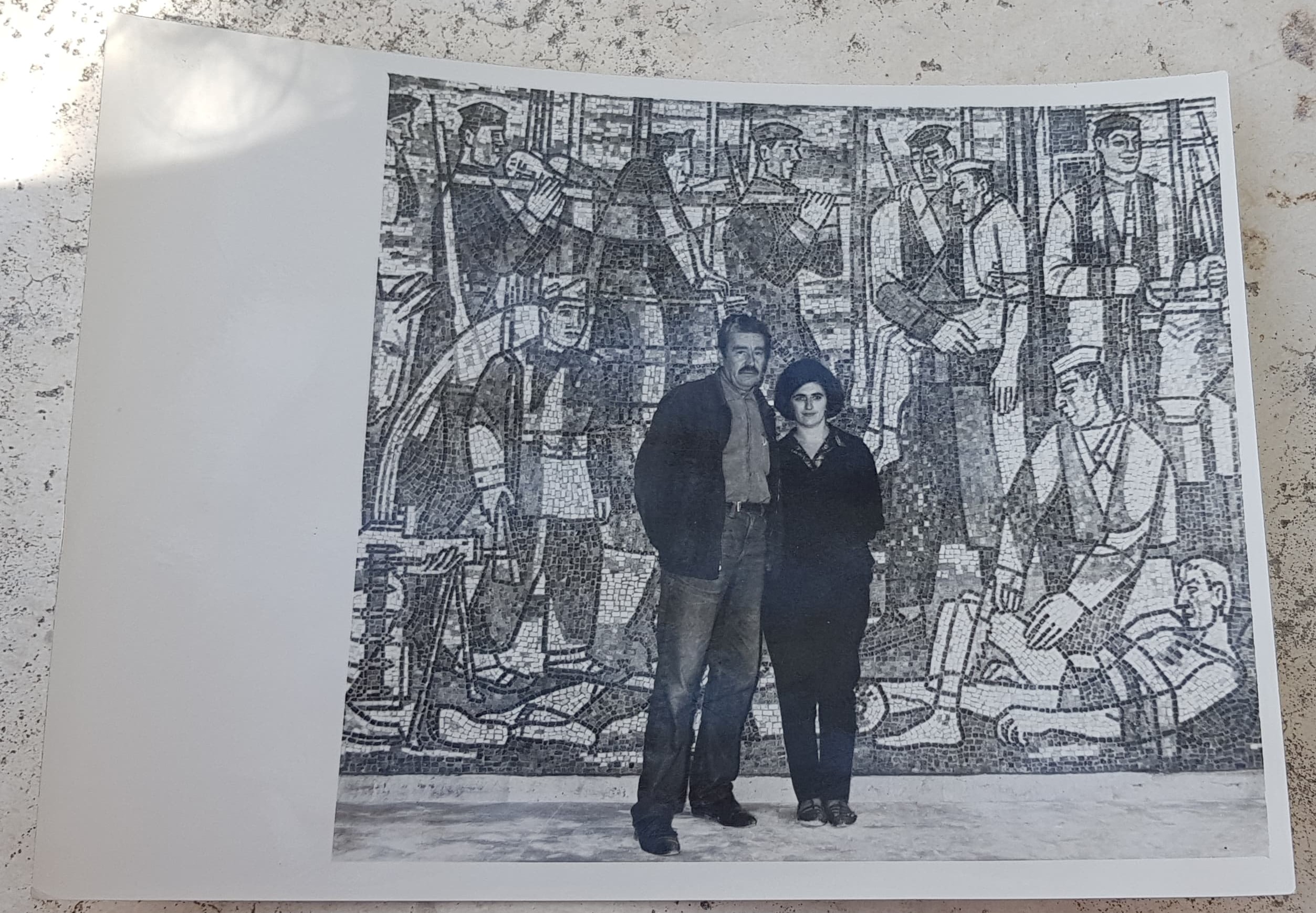

The wife of Ivan Joko Knežević and friends, standing in front of the mosaic in Omiš after the unveiling of this work of Croatia Public Art © Knežević family archives

This is not the only time the work of the rather brilliant Ivan Joko Knežević has undergone such a fate. Croatia’s only true master of mosaic operating in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, his incredible ‘Narod u svojoj težnji k stalnom napretku’ mosaic was a proud feature adorning the walls of the former military hospital in Križine, Split until Croatian independence. Thereafter, it sat behind a closed curtain for 15 years until some of the city’s more enlightened residents insisted the curtain be removed. Happily, this work of Croatia Public Art is now back on display.

Ivan Joko Knežević standing in front of his Croatia Public Art mosaic at the former military hospital in Split © Knežević family archives

Spomenik narodu-heroju Slavonije (Monument to the hero people of Slavonia) was a former World War II memorial by Vojin Bakić. So gigantic was this stainless steel monolith of gratitude that it took over a decade to build. After completion, it was the largest postmodern sculpture in the world. It took a concerted but incomparable five-day effort by bored soldiers with leftover explosives to destroy it following the end of Croatia’s war of independence. Today, such structures of art are recognised and hugely appreciated by many. Fans from all over the world travel to see them. Located in Kamenska, Brestovac, one of the most deprived areas of Slavonia, there is now nothing for the tourists to come and see except the lubenica (watermelon) growing slowly. So, they do not come.

Spomenik narodu-heroju Slavonije (Monument to the hero people of Slavonia) by Vojin Bakić. Built over 10 years, it was the largest postmodern sculpture in the world. It took five days to destroy with explosives © Public domain

Of course, the removal of the latter examples are rooted in a change of regime and political climate. Whether you approve of the recent removal of statues of slave traders in England in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, the famous toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue following the liberation of Baghdad or the destruction of world heritage sites like Palmyra by Isis depends only on your personal perspective and politics. It is all the same thing. The removal of Zagreb’s ‘Little Prince’ just seems like thoughtless vandalism in comparison.

Neighbourhood authorities in Dubrava have promised the return of the much-loved mural, a feat complicated by travel restrictions as its author lives in Novi Sad, Serbia. For now, city residents will look at nothing and curse the shortsightedness of the ‘Big Blue Babies’ who removed it. But, can they really be so harshly blamed in a country with a history for such wanton destruction of art that is never replaced?