An overview of numerous border disputes between Croatia and its neighbours.

Among many problems which burden relations between republics of former Yugoslavia, one of the main issues are numerous border disputes which are a consequence of the fact that Yugoslavia, while having strictly defined borders with other countries, did not have precisely marked or defined borders among its constituent parts. While the disputed areas are usually relatively small, they represent a major headache for governments of now independent states, since they are under pressure from the media and voters not to compromise and “give away” an inch of supposedly their territory.

Among all former Yugoslav republics, Croatia probably has the greatest number of disputes with neighbouring states. The only republic which is not arguing about borders with Croatia is Macedonia, and the simple reason is that the two countries do not share a border. While patriotic Croats like to say that the reason for that is the fact that Croatia is the most beautiful of all former Yugoslav republics and that all other nations are envious and want to take a piece of its territory, a more realistic assessment is that Croatia, due to its irregular and unusual geographic shape, has very long borders given its size and therefore it is only logical that it has many disputed parts of the border.

While it is impossible to list, let alone explain, all the disputes concerning Croatia, here is an overview of some of the most important ones.

Slovenia

Border disputes with Slovenia and Croatia are certainly the most well-known of all. Not only do they burden the bilateral relations, but they even delayed the entry of Croatia in the European Union. The most important part of the dispute concerns the border at sea. At issue is whether the border should follow the middle line between Croatian and Slovenian coast (which would mean that Slovenian sea would border just Italy and Croatia), or should be drawn in a way which would allow Slovenia to reach international waters. The dispute has been unsolved since early 1990s, with occasional incidents at sea between police and fishermen’s boats. There were repeated attempts by the two governments to come to an agreement, but they would inevitably be impeded by pressure from the media and public against any compromise.

Slovenia knew that the best time for agreement to be reached was during Croatia’s accession negotiations with the European Union. Since Slovenia had entered the EU earlier, it was able to blackmail Croatia and that is exactly what it did in 2008 when it blocked the negotiations. The move caused a complete breakdown in relations, with Croatia accusing Slovenia of hostile behaviour. After Ivo Sanader, Croatian Prime Minister at the time, resigned in July 2009, new Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor made the unblocking of negotiations a priority. Later that year, Kosor reached an agreement with Slovenian government that negotiations would continue and that the border dispute would be decided by arbitration proceedings. In return, Slovenia unblocked the negotiations and Croatia became a member of the European Union in 2013.

For a while tensions calmed down. However, it was becoming increasingly clear that the arbitration tribunal would probably rule in favour of Slovenia, particularly since the agreement between Slovenia and Croatia mentioned that Slovenia would have a “junction” with international waters. And then, in July 2015, media published secret recordings which proved that supposedly independent Slovenian arbiter was in collusion with Slovenian Foreign Ministry. Croatia immediately jumped at the chance, announced that the arbitration had been “irrevocably compromised” and that Croatia would no longer take part in it nor would accept any ruling. The Slovenian arbiter and an official at the Foreign Ministry resigned, effectively admitting their guilt, but Slovenia argued that the arbitration should continue nevertheless. After some deliberation, the tribunal agreed with Slovenia and announced that the proceedings would continue. But Croatia is still refusing to have anything to do with it.

The key question is what will happen once the tribunal issues its verdict, which will probably happen later this year. One possibility is that the ruling will go in favour of Croatia, which would probably end the whole controversy (no doubt, Croatia would suddenly change its mind and accept such ruling). But, it is much more likely that the ruling will be in favour of Slovenia. While Slovenia has announced that it would implement the decision within six months of it being announced, it is not sure what will be the reaction of Croatian government if Slovenia, for example, sends its navy or police to the disputed waters. No one knows what will really happen, but it will certainly not be anything pleasant.

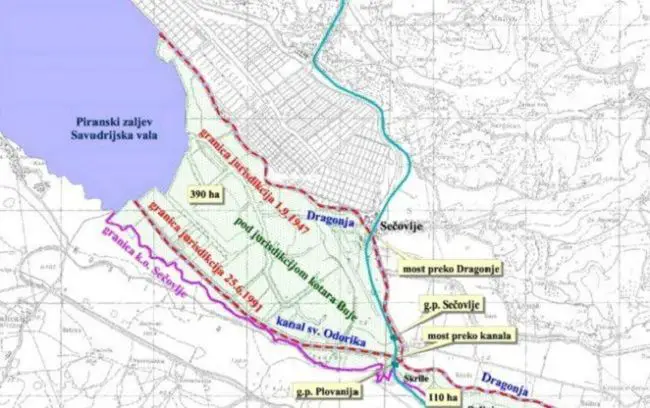

The arbitration proceedings which Slovenia accepts and Croatia rejects are expected to rule on the land border as well. There are several disputed sections of the land border, with the one in Istria being very important, since the end point of the land border will influence the sea border as well. River Dragonja in Istria used to be a border, but when an artificial channel was made about 500 metres in Croatian territory in order to control flooding decades ago, Slovenia decided that this was now Dragonja and that the border should be there.

Another point of contention is Sveta Gera peak in Žumberak hills. Actually, even Slovenia more or less accepts that the peak itself and a military installation which is located there belong to Croatia, but that has not prevent its army from “occupying” the facility for the last 25 years. This was the first major border dispute between the two countries, but in recent years it has been somewhat overshadowed by the sea border issue. There are also several other sections of the land border which both countries claim for themselves.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Compared to the border with Slovenia, disputes with Bosnia and Herzegovina seem insignificant, but listening to some politicians you could get the impression that it is the most important thing in the world.

One area is Klek, a small peninsula near Bosnian coastal town of Neum. While the peninsula itself is not disputed, with both countries accepting that it belongs to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia claims that its very tip should actually be part of Croatia, together with two small islands next to it, Veliki Školj and Mali Školj. Both islands are uninhabited and too small to serve any useful purpose, but Croatia insists that it should have control over them. While Croatia has hundreds of similar islands in its part of the Adriatic Sea, Bosnia and Herzegovina has a very short coast around Neum, and these two islands would virtually be the only ones it would have, so they have great symbolic importance for it as a supposedly “maritime” country. Another disputed area is a part of the border near Hrvatska and Bosanska Kostajnica, where at issue is a small castle currently controlled by Croatia, with both countries claiming it as theirs.

In the late 1990s, then presidents of the two countries, Franjo Tuđman and Alija Izetbegović, signed an agreement on the border demarcation, which provided for the disputed area at Neum to be given to Bosnia. However, the Croatian Parliament never ratified the agreement, claiming that a mistake was made by experts who were working on maps which are part of the agreement. Interestingly, then Croatian President Tuđman was never accused by “patriots” of being a traitor for signing such an agreement, as opposed to Prime Minister Račan, who in early 2000s tried to solve border problems with Slovenia by almost coming to an agreement with Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek and who is still being blamed for all the border problems with Slovenia (any many other things).

Montenegro

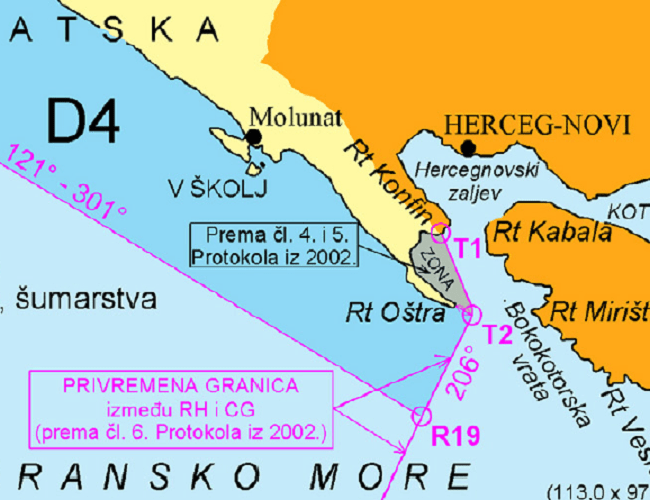

Montenegro is the smallest of all of Croatia’s neighbouring countries and its part of the border is the shortest one, so it is understandable that there is just one disputed area. It again concerns sea border, at the Prevlaka peninsula, which is with its Oštra Cape the southernmost tip of Croatia. In 2002, Croatia and Montenegro signed an agreement on temporary border regime. There have been no major incidents since, but it has still not been defined whether the temporary line will be turned into a permanent one. There were some disputes between the two countries when both of them announced tenders for oil and gas exploration in the area, with both countries claiming that the other one had no right to publish such tenders, but tensions soon calmed down.

Serbia

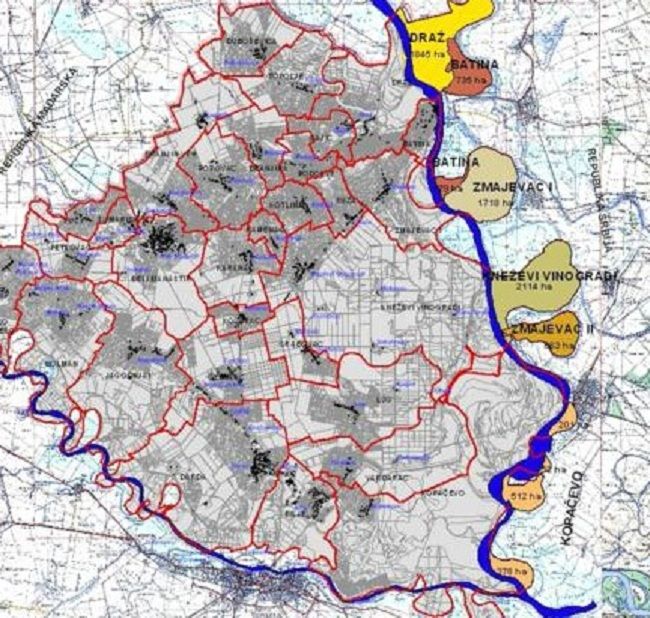

Every list of Croatia’s problems has to include Serbia, and this one is no exception. If you think that the fact that the border between them is in a large part defined by the Danube, one of major European rivers, would make it easy to know where the border is, you would be wrong. The Danube has an unfortunate habit of changing its course, which leaves an open question of whether the border moves with it or not. Croatia claims that the border should follow an old course of the river, while Serbia wants the border to follow the middle of the current course.

According to Croatian proposal, both countries would have significant parts of territory on the “wrong” side of the river. While a perhaps logical solution would be for the two countries to exchange these pieces of land, the problem is that Croatia has about 10,000 hectares of land on the Serbian side of the Danube, while Serbia has just 1,000 hectares on the Croatian side.

Any compromise about borders is difficult, but when it comes to the border with Serbia, it is absolutely impossible that any Croatian politician would survive giving an inch of territory. Since the border area was occupied during the Homeland War and was only returned to Croatian jurisdiction after seven years, in 1998, the pressure from the public and the media would be impossible to resist. And, while “our people have bled for this land” argument is being used against compromise for all the disputed territories, in the Danube area that it literally true, making any compromise virtually unattainable.

The border on the Danube does not involve just the territory on the other side of the river, but also the issue of small pieces of land in the middle. And that leads us to Croatia’s final border “dispute”.

Liberland (?)

While border disputes usually involve two or more countries claiming that the same piece of land or sea belongs to them, due to peculiarities of the border dispute on the Danube, there are several areas which Croatia claims belong to Serbia, and Serbia claims belong to Croatia. One such area is Gornja Siga, a 7-square kilometre large uninhabited area on the Croatian side of the river. In 2015, Czech politician and activist Vit Jedlička proclaimed “the Free Republic of Liberland” there, saying that, since both countries claim that they do not want the territory, it was “terra nullius” and could be claimed for a new state.

Reactions from Croatia and Serbia were different. Serbia announced that, although it considered the whole affair to be a trivial matter, the “new state” did not impinge upon the Serbian border, which it believes should be on the Danube river. Croatia, which currently administers the land in question, has stated that, after the resolution of the border dispute, the territory will be awarded to either Croatia or Serbia and therefore cannot be considered as “terra nullius”.

People coming to the island, including “President” Jedlička, have been occasionally arrested by Croatian police, which appears confused whether people should be arrested when coming from Croatian or from Serbian side of the river. Croatian courts first ruled that it was forbidden to cross from Serbia to Liberland, but then realized that they were actually confirming that the area was not part of Serbia, which was precisely what Serbia wanted. In later verdicts, courts ruled that it was forbidden to enter Liberland from Croatia.