November 27, 2019 – Filipa Marusic continues her look at the considerable UNESCO heritage in Croatia. Next up, World Heritage Site the Stari Grad Plain on Hvar.

The Stari Grad Plain is a cultural landscape that has remained almost the same since the Ionian Greeks came from Pharos in the 4th century BC. This heritage has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage list since 2008. It showcases the ancient geometrical system of land division used by the ancient Greeks called the “chora” which has remained intact over 24 centuries.

The agricultural activity in the chora was always here and based on grapes and olives the same as it was set up by the ancient Greeks 2400 years ago. The shape of the land division is the same, and the structures built by dry stone walling are authentic and reused throughout time. Additionally, this is a unique example of the land parcel system introduced by the Greeks. The cadastral division of the Stari Grad Plain is one of the best-preserved examples of Greek ancient culture in the entire Mediterranean. Despite all the historical and political changes over the centuries and multiple divisions of the plain, the Greeks set the structure. The Greek chora is embodied in the dry stone wall, which marks the land division. All later divisions of the land – Roman, medieval, or newer were always respecting the Greek shape and had the same dry stone walling technique. There is evidence of all different cultures who used the plain throughout time. The evidence is different archaeological findings dating all periods, from pre-history to medieval times.

The Stari Grad Plain is the biggest and the most fertile plain on the Adriatic islands. It had and still has its agricultural use, and local people grow the same cultures – olives and grapes. Archaeological findings prove the local inhabitants had their faith in the fruitfulness of the plain. In medieval times the plain was under the protection of the patron saint of Hvar diocese St. Stephen. The Hvar statute from 1331 mentioned the plain, and it listed roads and borders of the plain and several place names for places with later discovered archaeological evidence. The Stari Grad Plain changed its names according to how its owners changed. Different names include Greek Xωpa Φapoυ, Roman Ager Pharensis, medieval Campus Sancti Stephani, or today Stari Grad Plain.

The precise boundaries set by the Greeks in the plain are the work of villagers who used dry stone walling techniques even in ancient times. Some are just a barrier between two different lands, while others are quite wide and were in use as paths. Around the plain, there are circular stone houses called “trimi” or “bunje” used in the past as storage and shelter during bad weather. While the land here is fertile, the Mediterranean climate often has dry weather, so the plain has several reservoirs for collecting and saving the rainwater. All the different buildings located in the Stari Grad Plain range from the remains of farmhouses and drystone shelters to churches and chapels are there to prove the reusability of all the elements through centuries.

The Greek origin is visible in the very island name coming from Greek word Pharos (Faros), which ancient Greeks from Pharos island in the Aegean Sea gave when they arrived at where is now Stari Grad in 4 century BC. There were about 1000 inhabitants sent to colonise Hvar island. When Pharos became an independent Greek town polis in the 1st century BC, the Romans named the island Faria. In early medieval times, when Croatians came to the islands, they took over the names which locals used and adapted it to the Slavic language – this is how we have Hvar island name. Most Greek colonisations happened from 8th to 5th century BC, and there were about 700 colonies in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. At that time, there were just a few Greek colonies in the Adriatic Sea, so Adriatic islands were the only uncolonised part of the west from Greece in the 4th century BC.

There is some prehistoric evidence dating back to Neolithic times (6000-3000 BC), which proved this fruitful area was inhabited much earlier than the Greeks. Additionally, there are findings from the Bronze and Iron Age as evidence the Greeks found native inhabitants on Hvar when they first came. Also, at the time, Illyrian tribes lived in this area, and islanders cooperated with Illyrian tribes on the mainland. When Greeks from Pharos came to Hvar, apparently, there was at first peaceful agreement with local inhabitants. Later on, this agreement wasn’t respected, so local natives decided to attack the colony. As the land division was one of the main tasks of colonisation, this was probably one of the reasons for the conflict. We also know that the Greeks built the town on the coast with fortifications. This fact, along with the land division, meant then needed a lot of money at the time to do that.

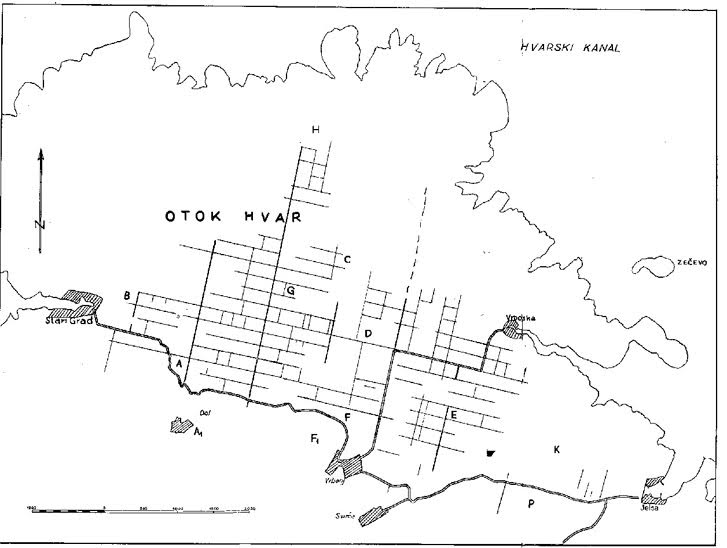

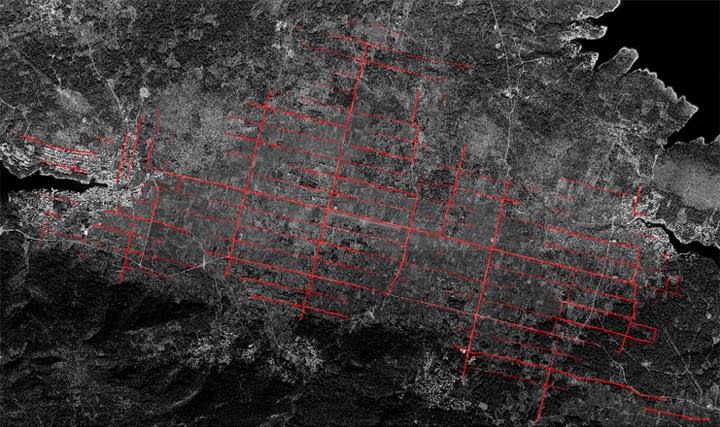

The cadastral plan and air image of the plain show that the border around the land has a size of about 180×900 m, no matter the division within this land part. The ancient Greek measuring system contains the measures that were in use. 180 m was the length of the Greek stadium while 900 m have five stadia. The average width of the roads was 10 Greek feet or about 3 meters. The Greeks used different sizes for this measure, but here research discovered it was 0,3026 m, and it was probably a standard measure in 4th century BC for some Greek towns. All the divided land in the direction east-west are parallel and break in one central point in the direction north-south. In ancient Greece, this point was called “omfalos” and represented the central unit where different paths meet. The land measure excluded the connecting roads. The base for the plain is karst terrain with several slopes where the land can quickly erode, and this is why people built so-called terraces or support walls. The terraces and dry stone walling is a valuable heritage people nurtured for years.

The chora had farmhouses, but there are just a few found as they were probably the foundation for Roman villa rustica. In the area, two guard towers protected the land. Additionally, there were perhaps temples dedicated to gods of fertility. There weren’t many Greek inscriptions in the area, but there is a stone fragment where it said “Border of the land of Matija, son of Piteja” which meant people of the time respected their land borders. Another larger inscription is evidence that local people of Pharos set three members to Greek Pharos to ask for money to renew the city, which proves they had a democratic setup. The local Greeks also were equal in terms of land amount and had similar housing.

The ancient Pharos even had its mint, but as Greek Paros didn’t have their own money, they used money from Greeks on Syracuse as inspiration. There are numerous versions of money from this area, as well as coins from different regions proving there were plenty of trades going on in ancient times. The ancient vessels and vases from the area show they were imported from Greece or locally made. The end of Pharos ancient Greek town is not known, but there is evidence of Roman building activity from 1st century BC.

In ancient times the most important agricultural products were wheat and olives. The plain area divided this way gave good income to people – if they grew just wheat, the market surplus was between 41000 and 157000 silver drachma (one drachma was the daily income of the worker and its equivalent of approximately 30 EUR). The Greeks planted olive trees and produced wine, figs, rosehip, almonds, carob, and other cultures. They went fishing, hunting, and were beekeepers. They also had cattle for food and for towing and carrying loads. The different amphora remains proved there was active production of wines and olive oil. The ancient Greeks probably had food supplies and stored the food for the time of war and as protection against robberies.

Toward the end of ancient times, Hvar island was quite well inhabited, especially the Stari Grad Plain area. As already mentioned, there are some early Christian churches which have medieval artifacts as well as circular dry stone shelter buildings from different periods. The Stari Grad itself has a range of different structures from the late ancient period to the end of the 19th century, which together create urban complex. From medieval times the bigger ancient lands were divided into smaller parts, and they reflect the changes through centuries.

When it comes to everyday life around Stari Grad plain was always connected to agricultural works depending on the season. The Hvar statute from 1331 gives the oldest written advice on agricultural work. Even today, the same rules are used in agriculture – the first warmer days after winter are for work, and this is the hardest part, and then summer is to keep the vineyard from any diseases. September is the month of harvest, followed by winemaking in October. November is olive picking, and December and January are for rest. From all the agricultural cultures, there are mostly grapes and olives but also lavender and rosemary, as well as other fruits grown here from ancient times. When some of the vineyards were destroyed at the beginning of the 20th century, lavender became part of Hvar’s agricultural heritage. Rosemary is another aromatic herb growing on Hvar and other parts of the Adriatic coast. The vineyards and winemaking heritage are part of local identity for centuries. The authentic Dalmatian variety plavac mali grows here as well as indigenous Hvar variety of white wine bogdanuša and prč and red wine drnekuša. Olive trees were probably on Hvar even before the arrival of Greeks, but their arrival meant the beginning of cultivated olive groves.

The religious celebrations set the time for the biggest local festivities. At Easter time, there is a unique procession Za Križem during the night from Maundy Thursday to Good Friday, which has been the same for more than 500 years going from different villages and towns around the Stari Grad Plain. TCN wrote about this unique UNESCO protected heritage in several pieces. At Christmas time there is kolendanje – groups of children or adults sing old songs with good wishes for the year that is to come in front of the houses of friends or neighbours. The special occasions ask for special meals such as starogrojski paprenjok – a pastry made from honey, flour, olive oil, prošek and different spices. It represents local traditions and uses locally produced ingredients.

If local people didn’t use the Stari Grad Plain, the valuable heritage wouldn’t be at such a good level of preservation. The Stari Grad Plain is the best-preserved example of the Greek land division, and it stayed that way as locals continuously used the land throughout the centuries. The dry stone walls which were built and rebuilt saving the shape of the parcels. The value of the Stari Grad Plain encouraged local and state authorities to work on the revitalisation of old parts of the plain with planting traditional agricultural varieties and promoting this heritage in the cultural aspect of Hvar tourism. The idea is to keep the same shape and land parcel system set by the Greeks and keep all the paths and routes around the lands the same without the use of any modern building techniques. The idea is to renovate all the buildings according to the traditional way and reuse them for tourism purposes and keep archaeological researches active.

For more information about the Stari Grad Plain, visit the official website.

To learn more about Stari Grad, here are 25 things to know.