When Croatians say “prošek”, they mean sweet, dessert wine made near the Adriatic coast from the grapes that have been dried in the sun in order to concentrate the sugar in their juice.

When Italians say “prosseco” (admittedly, the two words do sound alike), they mean the sparkling wine, produced exclusively in the northern Italy, made from the glera grape variety (often blended with other white wine varieties).

Having read those two sentences carefully, you are fully aware that those are two different things. What you’re now probably wondering is why are those two completely different products called almost the same? The answer probably lies somewhere near the Italian village of Prosecco, where in the past wine from the variety then called Prosecco was made – sweet, still white wine. Since those times when the name was first shared, the Italians embraced the secondary fermentation technique (different than the one used to make the French Champagnes) in the early 20th century, and started producing high-quality dry sparkling wine in the 1960s. All that time, prošek that is made on this side of the Adriatic has remained almost the same, and it’s well known that it has been produced using the same techniques for almost 2000 years, and that it was even sold as a medicine in Dalmatian pharmacies, including the oldest European pharmacy in Dubrovnik.

However, the Italians have managed to get an EU protection of their prosseco, and due to the lack of understanding of Brussels bureaucrats and most probably not enough effort and knowledge of the Croatian negotiators, succeeded in extending that protection in a way that Croatian wine producers are barred from using the word prošek to label their wine. The explanation given by the EU states that the names are too similar, which could lead to a lot of confusion for the buyers? Since, there were several alternative explanations of what the EU directive means, and Croatian producers still make and sell prošek, as it is virtually impossible to impose such a ban – especially on the level of family producers, where most prošek has been made and consumed anyway.

So, how, where and from which varieties is prošek made? It’s usually made in Dalmatia and on the Dalmatian islands; however, there are prošek producers in Istria and also on the northern Adriatic islands. The varieties used to make prošek vary, but usually those are indigenous Dalmatian varieties, such as vugava, bogdanuša, maraština, malvazija, babić and plavac mali or less-known indigenous red-wine varieties.

All of those varieties can accumulate a lot of sugar given enough time to ripen, and then a method used to create other similar types of dessert wine, so-called straw-wine (or raisin-wine) is used: the fully ripe grapes in perfect condition (no diseases, no bruises, no damage of any kind) is hand-picked and let either on the sun or in the shade to dry further. There are a lot of variations to the well-known passito method (used in Austria and Germany as well to create their strohwein, in France for Vin de Paille and in Italy the wines made this way are called generically passito), so some producers will leave the selected grapes on the vine itself to dry, and the method should be distinguished from similar methods of creating dessert wines, such as ice wine (where the grapes are left on the vine very late, until after the first frost of the season), or noble rot technique.

As the grapes dehydrate during that drying process, the sugar in them gets more concentrated, and the first step in the process of creating prošek is always manual (or, actually, more often it is pedal) crushing of the somewhat hardened and shrivelled berries. Then you need to use special yeasts that are able to work in such extremely high sugar content in order to get alcohol, because the usual yeast strains cannot do it under such conditions. What you need to achieve in the end, after a year of fermentation, is a wine with at least 15 percent alcohol content, that has a lot of remaining sugars (because the starting sugars are so high there’s no way all of it is going to get fermented into alcohol) and relatively high acids that balance the flavour. Unfortunately, some family producers will try and simplify the process by adding sugar to the grape extract before the fermentation or concentrate the juice by cooking the excess water out of the must, but that results in much lower quality of prošek and is completely abandoned by the notable producers, who are trying to create wine of the highest quality.

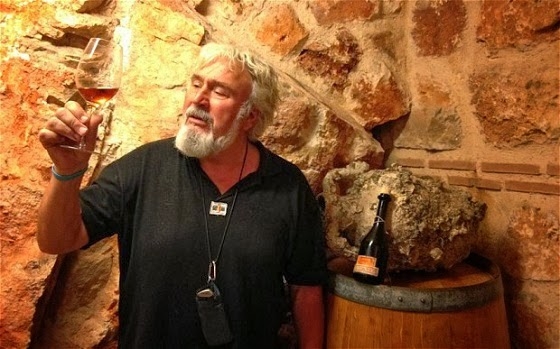

Prošek is almost always aged in smaller oak barrels, as the wine must be matured for the flavour to evolve and harmonize with the alcohol and the acids in the wine. It ages exceptionally well, so it’s a tradition to keep a bottle of prošek made in the year when the child is born, and open it on the day of the person’s wedding! The colour of prošek depends greatly on the grape varieties used, but is almost always darker, amber or even copper brown (of course, some prošek is made with red wines such as plavac mali, and its colour is quite different and much darker), so it looks a bit like sherry or Madeira wine. And, yes, you should serve (and taste) it from a glass made for dessert wines, port, Madeira or Sauternes glass – smaller and round-bottomed, as it has high sugars and high alcohol, prošek is not the type of wine you’ll have much of.

Because of the method described, which uses highly dried-up berries to produce wine, the volume of wine you get at the end is very low (compared to traditional methods where you take the full berries and crush them), so it’s very expensive to produce prošek. That’s why, traditionally, it is much respected in the Dalmatian family, served only on special occasions, saved for Christmas or a visit from a teacher, doctor or a priest, and offered with a sense of pride – because it is considered to be the best product an amateur winemaker can make.

Have it with a dessert, if you get the opportunity, served at around 16°, and make sure that it’s a dessert made with traditional produce found in Dalmatia: figs, almonds, carob cakes, as prošek accompanies those best. And some experts say that prošek is the dessert wine that you should have with really good chocolate (supposedly works even better than a tawny port), so if you get a chance to give that a try, don’t miss it.

Prošek has, unfortunately, lost some of its popularity in Croatia in recent years, so it won’t be easy finding and buying good prošek. Long-time favourite is Hektorovich, prošek made by the Hvar winemaker Tomić, the wine that made its way to the cover of the La Revue du Vin de France magazine. Brač winery Stina makes their prošek from plavac mali and pošip grapes, and boasts that they are the only commercial producer that uses the traditional method to make prošek. PZ Vrbnik from the island of Krk makes prošek with vrbnička žlahtina, a local favourite. Hvar’s Plenković also makes prošek from plavac mali grapes.

Prošek is usually sold in smaller bottles (up to half a litre), and is quite expensive – so make sure you give it a try before you buy it, and if you’re buying from a smaller producer, inquire a bit about their methods before they convince you that what they have is a traditional prošek.