May 31, 2018 – Lazy weekends on the Dalmatian coast are a great way to get to know the locals and their memories of the Mediterranean as It Once Was.

People sometimes ask me how I can write so much about Croatia, and where I get the constant supply of ideas for stories.

It is an easy question to answer. Croatia has some truly fascinating characters and history, most of which is not written down, certainly in English, and the simplest chat with almost anyone here can result in a story worth publishing.

Last weekend, I accepted a kind invitation to join good friends for a weekend on the coast in the village of Zaostrog, near Makarska. They were going down to chill, I was on a mission to lock myself in a room without distractions and work 16 hours a day, joining them for dinner.

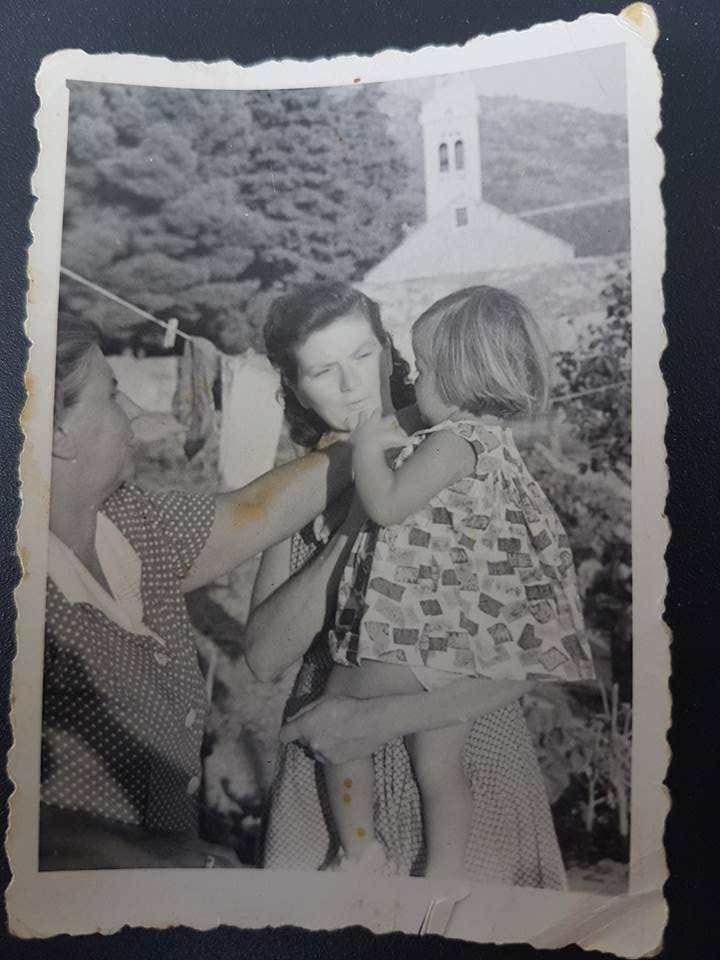

(Young Ivo, bottom left, with family around the time of the earthquake)

Our host Ivo, who runs his Home Faraway apartment business in Zaostrog, was very welcoming, and we got into a little chat one evening about how life used to be in the village. When asking about his childhood, he told me about the big earthquake in Dalmatia in January, 1962, which struck near Podgora, some 20km away (6.2 on the Richter Scale), and left a profound impression on his childhood. He kindly agreed to get out his old photographs and let me record the story through his 8-year-old eyes.

The first quake struck on Sunday afternoon about 14:00. Ivo was playing outside his house on some stones and they all scattered, sending him tumbling too. It was not too big a tremor, but he remembers how all the animals were acting strangely before it hit – they knew something was afoot. Everyone came out onto the street but the damage was not so bad. There were several tremors over the next few days, but nothing too severe.

And then it happened. At 4am on a Thursday morning with the whole village sleeping. They awoke covered in bits of concrete from the ceiling, and there was hardly a building in the village which was left habitable. And while this was obviously a nightmare scenario for the parents, so began a great adventure for young Ivo, which began with two nights in tents in Zaostrog, as there was nowhere habitable in the village. The belltower of the church collapsed completely (see lead photo) and there was a lot of stone which fell down from the mountain behind the village. He remembered that one person died, an old lady, and there were several injured, including his brother (who now lives in Sydney), who emerged with a broken arm.

And then a ship appeared on the jetty, collecting all the women, children and old people from the neighbouring villages. It left at about 18:00, already dark in the Dalmatian winter, and the ship sailed north. The men were left behind to rebuild the village. At around 10:00 the next morning, the Dalmatian party arrived in the city of Rijeka, the first time young Ivo had ever seen a city. It was exciting, and he felt like he had crossed an ocean.

Waiting buses took them to Opatija and the Hotel Belvedere, where they were to spend a couple of months as refugees, before switching hotels. It was in Opatija that he saw and tasted a banana for the first time.

There was school organised for a few months until they received word that the men had made great progress rebuilding the village, and they returned home in May. The house was not totally rebuilt, but it was habitable and things got finished gradually after that.

(Dad was busy while Ivo was in Opatija – a house for the returning refugees)

The following winter was the coldest he remembers, and snow fell all along the Dalmatian coast in 1963, up to 2m high, Ivo recalls.

I asked him what it was like growing up in a small village near Makarska. What were the roads like etc.

There were no roads, apart form a small one near the coast. There was a small school in the village, but only until 4th grade, after which kids would have to take a one-hour boat ride each way to school in Gradac further down the coast. If there was a fierce bura wind, there was no school that day. He recalls that there were two lines each way every day and often the salon was full, so the kids would be out on deck, huddling as close to the chimney to keep warm. Split was 6-7 hours away by boat, and the destination if you needed hospital.

There was a fast line along the coast, which included Zaostrog, coming from Ploce, then Igrane, Makarska and Split, but the general service was a slow boat which took in every village on the coast, and would also connect to Trpanj on the Peljesac Peninsula.

Ninth grade meant a new school in Makarska, and his growing up coincided with a new road built by Tito, which was started in 1964 and finished in 1966. That spelled the end of the local boat lines, as school and everything else was much quicker by bus.

I asked him about life in the village back then compared to today. When he grew up, there were about 600 people in the village, 400 in Upper Zaostrog, the old stone village in the hills, where the vineyards and fields were, and 200 down on the coast, whose inhabitants were mostly in the fishing industry.

(The old stone village of Upper Zaostrog today)

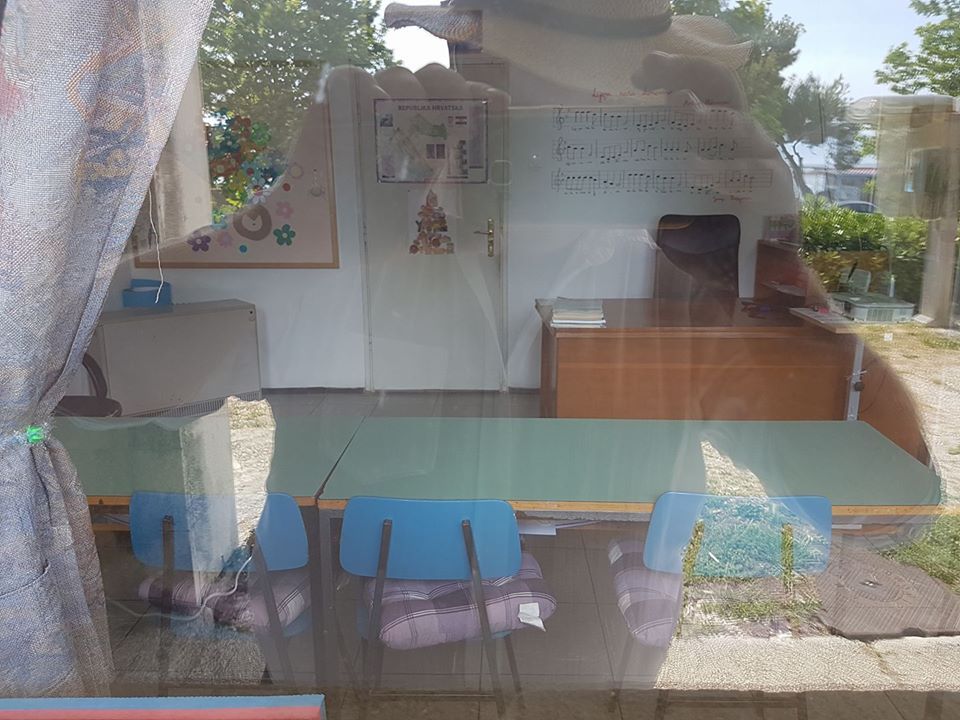

He remembers that there were 30 kids in his class in those first four years before moving to Gradac, about 100 kids in total. Today, the population of Zaostrog is 160 – he counted a couple of days ago, as winters are long, and there is not so much to do. As for the school, just three pupils these days.

(Zaostrog school in 1962)

This in a village which has seen 35 deaths and just two births in the last ten years. And that is without talking about emigration, a demographic reality which has affected Zaostrog as every community in Dalmatia over the centuries. The population peaked in the 1920s at more than a thousand, with the most popular emigration destinations being Australia and New Zealand.

{Zaostrog school in 2018 – just three pupils)

A little snapshot of Dalmatia, documenting a time long forgotten and largely unknown in English. There are many such stories you can hear during lazy weekends in Dalmatia this summer.