May the 14th, 2024 – Do you know the extraordinary story of a Dalmatian refugee camp in the Sinai Desert in Egypt? Let’s go back to WWII, and visit El Shatt.

One of the curious things about living on the island of Hvar after a few years is discovering that far from being an island where locals and their ancestors have stayed put in the surrounding area, there are some great tales of epic travels where you would least expect it.

Soon after I moved, I heard stories of locals whose parents had been in Egypt during the Second World War, then I met a woman who had been born there, and finally a man who had been born there and named after the desert which was his entrance to the world – Sinaj.

More conversations led to the realisation that there were not isolated incidents, but part of a much larger exodus of Dalmatians, who were moved from the mainland and islands in 1944 to the safer climbs of a refugee camp in Egypt, one that did not really exist before the first arrivals.

This is part one of the incredible story of Dalmatians in Egypt (1944-46): The Camp of El Shatt.

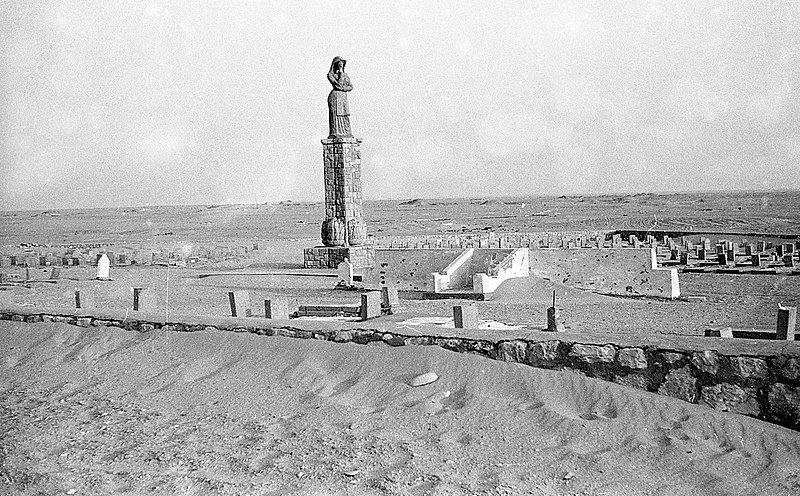

After disembarkation at Port Said, “we got into a long train composed of freight wagons… I was stirred by the halting of the train. The doors of the wagons opened. A weird yellow light glared in on me… I was hardly able to open my eyes from the light. A strange picture in front of me. A wide, yellow, sandy plain stretched into infinity… Oh, how unfriendly it was. Not a blade of grass, a flower, not a bug, butterfly or bird. Silence… and in front of the eyes flickered the ardent mass of the sandy plain.”

Those were the initial impressions Danica Nola, as described in her book, El Shatt, upon arrival in the Sinai Desert from Dalmatia, one of more than 26,000 transported to escape the fighting, many of them from Hvar. Here is part one of the incredible story of a fully-functioning Dalmatian camp in the Egyptian desert during the Second World War.

the italian surrender of 1943

The capitulation of Mussolini was first publicised by Allied radio from Algeria on September 8, 1943, and led to a rapid chain of events on the Dalmatian coast and islands. All islands, including Hvar, were liberated by the National Liberation Army (NOV) as Italian garrisons were disarmed, and the city of Split was freed on September 10.

Dalmatia’s freedom was short-lived, however, as the Germans were determined to keep control on the strategically important Adriatic coast. They sent in columns of troops and, after fierce fighting, retook Split on September 27, and gradually regained control of the entire coast and Peljesac Peninsula, before making a start on the islands with a landing on Korcula on December 21, and then Hvar on January 19, 1944.

1500 refugees on the islands

The refugee situation was desperate, and the islands’ population was swelled by more than 15,000 people fleeing the Germans, most of them on Hvar. The islands were struggling to feed their own populations, never mind the influx of desperate visitors, and it was clear that the refugees would have to be evacuated before the fighting which would ensue.

Agreement was reached with British military authorities to move the population to British-controlled southern Italy, and on October 1, 1943, the Bakar set sail from the island of Vis to Bari, carrying the first refugees. The evacuation had begun.

relocation to egypt

After negotiations between the British High Command and the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia (NKOJ), it was agreed that 10,000 refugees could be housed in Italy, with the rest being sent to camps in North Africa, which was also under British control.

Crucially, the two agreed that NKOJ would have full authority for the running of the camps, with no access allowed for representatives of the Yugoslav government of Draza Mihailovic, while the camp would be overseen by Allied Military Liaison.

And so it was that on February 1, 1944, Danica’s recollection above of her arrival in the Egyptian desert, came to pass.

Source: El Shatt, Zbjeg iz Hrvatske u Pustinji Sinaja, Egipat (1944-1946) by Hrvatski Povijesni Muzej