September 1, 2020 – If you are from Zadar, chances are you’ve heard a thing or two about the Zadar sphinx. But if you aren’t from the area? It’s possible you don’t have a clue.

Slobodna Dalmacija writes that although the people of Zadar claim to have the largest sphinx in Europe, hardly anyone outside their city knows about it.

The situation should soon change for the better, according to the Department for EU Funds of the City of Zadar, which raised 220,000 euro to restore the sphinx and promote this location in the city area of Brodarica. The funds were provided through the EU project Recolor. Several cities from Croatia and Italy are participating, and it intends to stimulate tourists’ interest in locations outside the city center.

The negligence of those in charge of the sphinx has been written about for years in the local media.

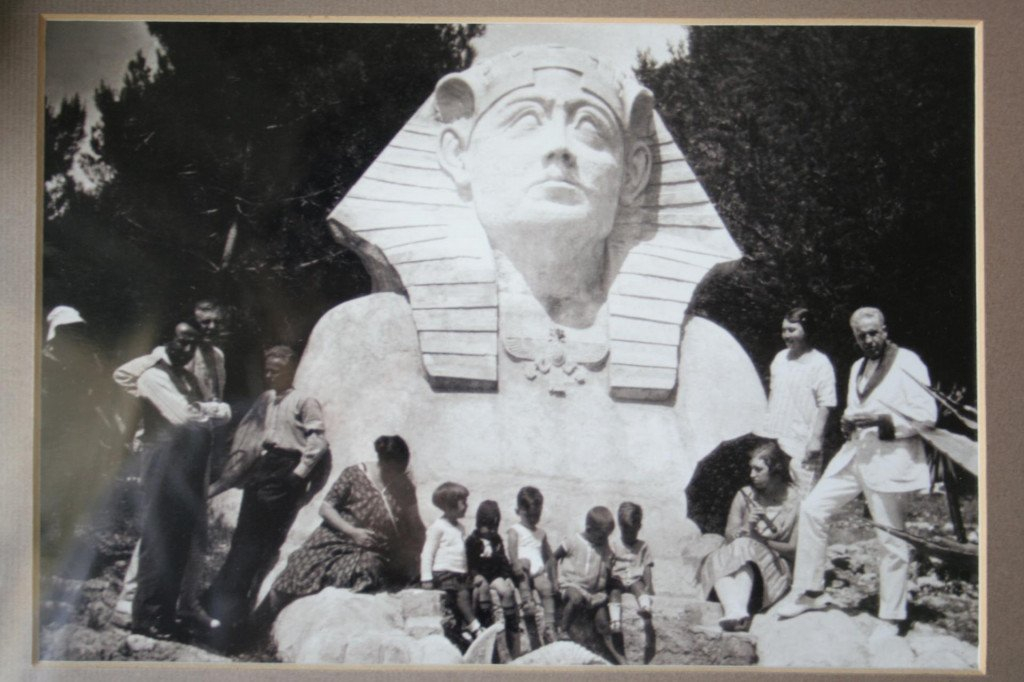

The space and the sphinx were, to some extent, cared for only by the actions of volunteers. Though neglected, the sphinx is fascinating. It is located behind a dilapidated fence in a once beautiful park. The classicist villa, Attilia (where the Health Center is today), belonged to the Smirich family (Žmirić). Along the lungomare, after a series of historicist, classicist, and secessionist villas, which have been renovated in Brodarica in recent years in the name of tourism, a large sphinx appears that looks dignified, despite its declined state.

The sphinx’s story begins after the villa Attilia was built in 1901, though little is known about who made such a large concrete sphinx, its significance, or when it was made. There is no preserved park design or original drawings of the sphinx. Today, it is a common story that it was built by Giovanni Smirich in 1918, as a sign of love for his late wife, Countess Attilia Spineda de Cataneis. He was a very important Zadar conservator responsible for the restoration of St. Donata, Sv. Stosije, Sv. Krsevana, Stomorice, Sv. Lovre, and was also the director of the first archeological museum in Sv. Donat, but he was not as important as the painter.

Gold was once thought to be buried beneath the sphinx; they tore off her hind paw, part of the thigh, and stripped the concrete from the north side of the trunk to dig it out. They even believed that there was a secret room under it.

Based on the sphinx’s face, it was rumored that Smirich’s wife was so ugly that he wouldn’t let her out. Today, this was rejected because the countess was not ugly, nor did she look like a sphinx, as can be seen from the family photos by the descendant of the Smirich lineage, Mario Padelin. On the other hand, some believe that Smirich raised the sphinx out of interest in the occult he nurtured with his wife.

The city’s tourist community seems to like the love version the most, judging by the promotional video.

Slobodna Dalmacija asked Dr. Antonija Mlikota from the Zadar Department of Art History, about the sphinx of Giovanni Smirich. She believes that Smirich, as the first Zadar conservator, should be indebted to the city by naming a street or park next to the sphinx after him.

“Smirich was a key person for the development of the protection of monuments and museology in Zadar. The more I research him, the more I am thrilled because I see how much he worked and had a wide range of activities and great knowledge of monuments and the past of Zadar. He was born in Zadar in 1842 and was buried there, in the city cemetery, in 1929. Although of Croatian roots, he was a great Italian, and he was proud of that.

He studied in Siena, Florence, and Venice, where he also met his wife, Countess Attilia of Treviso. They had four daughters and one son.”

She said it was “amazing that Smirich and his gardener made the sphinx in such well-hit proportions.”

“I think he took advantage of the possibilities of concrete and wanted to show what can be done with it. He and his gardener built it; it was his only help in building the sphinx. We know this because the great-grandson of Smirich’s gardener Sime Baric, Antonio Bari (Antonijo Baric), wrote a book about Smirich, the villa, the park, and his great-grandfather’s life in Zadar. It is fascinating to me how, without computers, precise meters, and redrawing, they managed to make a sphinx modeled on what they saw in museums or Split. It is very proportional, like a sculpture.

In addition, we found that one of his sons-in-law, Vladimir Bersa, made two replicas of the Split sphinx in wood, which Smirich kept at home, and which was shown to us by his great-grandson Mario Padelin. Perhaps the Split sphinx was a direct example of the Zadar sphinx, because the sphinx on the Peristyle is atypical in that it has human limbs between which it holds a vessel, while Smirich held a sword over a shell-shaped well,” Mlikota thinks.

The Egyptian sphinx on the Peristyle, 3500 years old, belongs to the type of sphinx representing a pharaoh who offers sacrifice in a vessel. It is believed that she was placed on the Peristyle to be the guardian of Diocletian’s Mausoleum. Although the inspiration may have been taken from Peristyle’s sphinx, we must note here that the sphinx’s meaning in Zadar’s Brodarica is different. There are no insignia of pharaohs on the head of the Zadar sphinx, no upright cobra or beard.

It is not known from the photographs whether there was a relief of Horus on his chest, representing the Egyptian god of the sky and war, or an eagle, as some claim, which would be a symbol of the Roman Empire (after World War II the relief was destroyed).

Beyond Egyptian mythology, in outstretched fists, the sphinx held a short sword of the ancient Romans gladius (later destroyed). It stood above a shell into which water flowed from a spring and flowed into fish ponds.

The sphinx can thus be understood not only as a guardian of the afterlife, but also as an earthly one (spring, fish), that is, as a protector of the household. But, for sure, with its large dimensions, which were not found in Dalmatian parks, the sphinx was conceived as an attraction that will capture passers-by’s attention.

The Roman sword gripping the sphinx shows Smirich’s preference for the Italian option. The Italians at the time were interested in Diocletian awakening territorial claims to Dalmatia because they claimed that the Italians were the heirs of the ancient Romans.

Giovanni’s father, Antonio Smirich, was a member of the Autonomous Party in the first convocation of the Dalmatian Parliament. In 1860, he requested that land registers in Dalmatia be kept in Italian, which provoked a reaction from Mihovil Pavlinovic. Giovanni’s brother Eligio Smirich was appointed governor of the Kingdom of Italy for Zadar in December 1918. With his appointment, repression of Croats and Serbs began in the city even before the Treaty of Rapallo. Giovanni’s son Antonio was a volunteer in D’Annunzi’s brigade when he set out to conquer Rijeka, and in 1926 he was appointed a member of the Italian delegation that shared the Zadar archives with representatives of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

Sphinxes used to appear as a park sculpture (two examples from Osijek from 1896 are good examples), but with women’s hairstyles, lush breasts and much smaller dimensions. However, that the sphinx could be used ideologically was shown in 1911 by Ivan Mestrovic at an international exhibition in Rome, where he won the first prize and was proclaimed the new Michelangelo. On that occasion, he exhibited the “Vidovdan cycle”, which promoted the unification of the southern Slavs, and the sphinx, forgotten in our country because it is in Serbia and was one of the main attractions.

However, there is no reliable evidence that the Zadar Sphinx was erected in 1918, or who the author is. Marija Staglicic, who thoroughly elaborated the architecture from classicism to the secession in Zadar, believes that the park and the house as projects were created simultaneously.

“There have been houses in the Brodarica area since the 1880s, but between 1900 and 1907, many Art Nouveau and historicist villas were built abruptly. Smirich’s house from 1901 was built quite early in relation to the others that grew sharply in that rather short period and is the first of a series of villas that were by the sea. I guess the park was created along with it. The goal was for these to be country houses that would have Mediterranean gardens. I didn’t find any information about it, no draft, I just have a draft of the villa itself.

I assume that it was created by Smirich himself, who was a man of the 19th century, although he partly lived in the 20th. The house is neoclassical, and the park is neo-romantic. Both are neo-styles and therefore fit into that time,” says Staglicic, who believes that Smirich designed parts of the park architecture, including the sphinx.

The Sphinx was probably conceived before Smirich’s wife died in September 2017, perhaps even before the war. Namely, he likely designed the park architecture together with the park, as it was usually done.

This is indicated by the arrangement of other elements in the park. An artificial cave, a fountain, a stone bench, and a semicircular bench, are placed on the left side or towards the middle. Had it not been for the sphinx, the southeastern quadrant of the park would have remained empty. It is hard to imagine that Smirich, who paid close attention to symmetry, as can be seen from his project for the fence between the bell tower and the Cathedral of St. Stosije, or the paintings “Annunciation” and “Spartan Court”, allowed such a discrepancy in space.

There is no content behind the great sphinx, because it “theatricalizes the space and life around it”, as Abdulah Seferovic concludes in the monograph on Brodarica. All this suggests that the sphinx was planned before the death of Countess Attilia.

If the sphinx was built only in 1918, as some claim today, although there is no official trace of it, it may be because there was a problem finding a contractor. Smirich, a painter, most likely did the design, but he had no sculptural experience, especially not working in such dimensions. The sphinx is almost three meters high and about five meters long. Moreover, in 1918 Giovanni Smirich was 76 years old.

It is unlikely that Mestrovic at that age also had the strength for a work of such dimensions.

Our famous sculptor, academic and professor at the Split Academy of Arts, Kazimir Hraste, believes that someone could not have created the sphinx without sculpture experience.

“The work is on a solid aesthetic level, which is noticeable from the harmonious proportions, and implies that the author was artistically educated. There was certainly a sketch-model in three-dimensional form for making such a large (in terms of dimensions) work, because that is the basic and easiest way to realize a large sculpture. Namely, the technique of transferring from a small three-dimensional form to a large one is well known.

It is an interesting fact that concrete was used for the realization, today a common sculptural material, but at that time a relatively new and primarily construction material. By choosing this material, the author reveals his character, which was obviously prone to new and experimentation,” says Hraste.

“The realization itself required from the author the synergy of builders, masons, stonemasons … old craftsmen in the service of the new ‘building’. Everything is guided by the hand of the author who saw the goal. Today, with the help of modern technologies, we can reconstruct and discover the way we work. However, many details will remain a secret to us. I believe that the author himself made the final layer of concrete. It is a skill of directly applying concrete to the substrate, similar to working in the stucco technique. Considering the size of the work, many surprising factors were encountered on the way to realization, which was obviously solved with a large amount of creativity, because there was no model for such a monument,” says Hraste.

Who then could have been the sculptor? The only sculptor educated in Zadar at the time was Bruno Bersa, his brother Vladimir Bersa married Smirich’s daughter, and both were brothers of the famous composer Blagoje Bersa. Bruno Bersa portrayed the dignitaries of that time, so he created Smirich’s bust. Bruno Bersa was educated in Vienna and Paris and could have taken on such a feat.

Another possibility is that the sphinx was made by masters and artists outside Zadar, from Austro-Hungary or Italy. Hraste says the Italians retrieved the concrete early.

Wartime and post-war times are times of poverty in which sculptors find it difficult to obtain commissions. Perhaps artists from larger centers came to the smaller centers and worked on garden sculptures for eccentric rich people, because they ran out of orders from the state and cities. And perhaps, they did not want these works to be known.

The City of Zadar said that the conservation study should be completed by the end of September, after which the state, which owns the land, will send the entire project. After approval, it is intended to renovate the sphinx and the concrete fence, which is in a rather poor condition, and to install benches and lighting.

The sphinx will certainly be cleaner, more beautiful, better lit and attract tourists more. Admittedly, even a damaged sphinx with a patina is not incompatible with the idea of a romantic park. How the restored sphinx will be accepted, remains to be seen.

For the latest travel info, bookmark our main travel info article, which is updated daily.

Read the Croatian Travel Update in your language – now available in 24 languages

Join the Total Croatia Travel INFO Viber community.