An ancient Croatian republic is ruled by a book of statutes that includes protections for women and dogs. A young heroine sacrifices her virginity to seduce a Turkish general and then blow up his Ottoman army, thereby saving the republic. Pirates troll the Adriatic, along the republic’s seaside territory. Books are written in Glagolitic letters, the oldest known Slavic script. Priests cast the deciding vote to determine who will reign as the next publicly elected Great Duke. All citizens of the republic are free and literate, and they all go into battle.

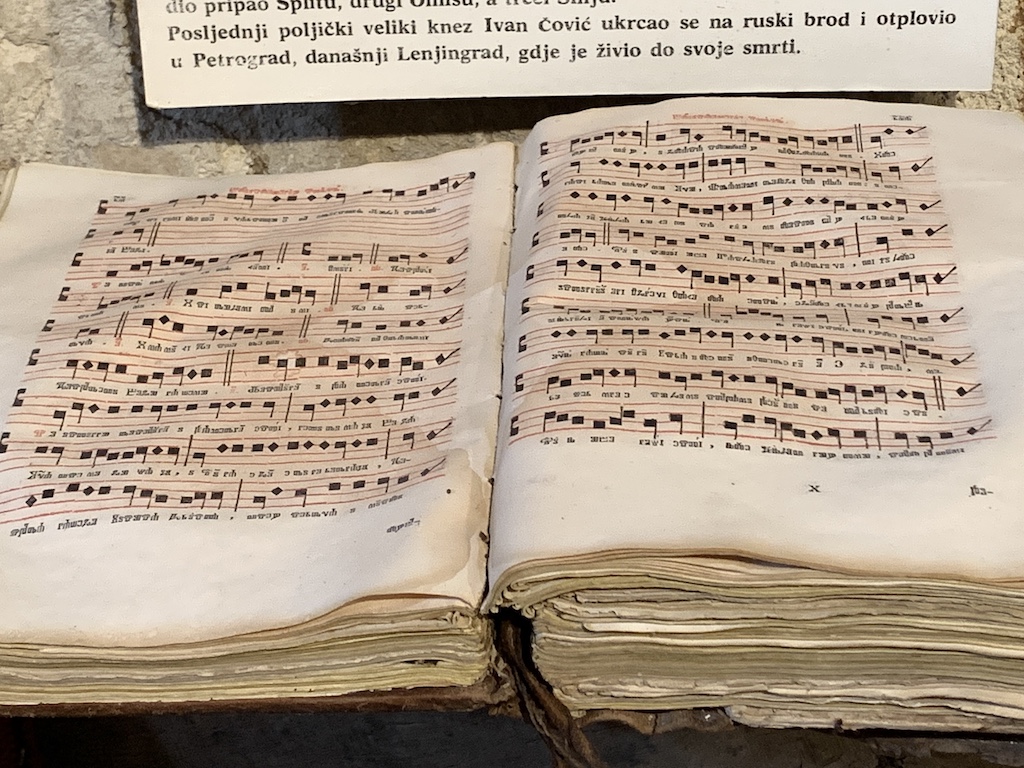

A book preserved from the early days of the Republic is written with the old Glagolitic letters.

A book preserved from the early days of the Republic is written with the old Glagolitic letters.

Poljička Republika

Still with me? Welcome to the Middle Ages and the Poljička Republika, an autonomous community that existed on the land between Omiš and Split for nearly 700 years. This peasant community was self-ruled with an original legal system, a progressive social structure, and independence from the rest of the country. The people’s values are the secret sauce that kept them unified and helped them survive throughout centuries, and boy oh boy do they make an impression.

A picture of a picture… a statue of Mila Gojsalić, the young Poljica heroine who helped defeat the Ottomans stands above Omiš; carved by Croatian sculpture Ivan Meštrović.

A picture of a picture… a statue of Mila Gojsalić, the young Poljica heroine who helped defeat the Ottomans stands above Omiš; carved by Croatian sculpture Ivan Meštrović.

Today, their exclusive costumes, novel dance, and unique songs are recognized on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. And here’s the culinary piece you’ve been waiting for… The people’s traditional “peasant food,” soparnik, is on the list too and it’s furthermore protected by geographic origin per the European Union. Wow.

This village kitchen displays a map of the Poljica region, here showing where the Upper, Middle, and Lower territories of the Republic sit around Mosor Mountain.

This village kitchen displays a map of the Poljica region, here showing where the Upper, Middle, and Lower territories of the Republic sit around Mosor Mountain.

Soparnik pie

The humble soparnik pie is a standout for its simplicity and its deliciousness and it’s possibly the best cultural ambassador for the ancient Republic and the current Poljica region. Once considered basic grub for the poor and workers, dating back to the Ottoman Empire, it’s still made from locally grown ingredients in the customary manner of the hinterland, including wooden equipment and an open stone oven.

A massive oak tree near the Church of St. Cyprian grew up during the heyday of the Poljica Repubic and is thought to range from 400-700 years old.

A massive oak tree near the Church of St. Cyprian grew up during the heyday of the Poljica Repubic and is thought to range from 400-700 years old.

Soparnik is easy and quick enough to make and it consists of flour, water, salt, olive oil, chard, onion, and garlic. So particular are the cooks, they can tell you the difference between onions grown in their back yard versus those on the other side of the mountain. With so few ingredients, this skill is a testament to the resourcefulness of people with little means, using their natural surroundings to create sustenance, which, by the way, happens to be quite tasty and filling.

In the kitchen

In family homes, Grandma Milka teaches granddaughter Mila precisely how to roll the dough on a sinija—a round wooden board that measures 90-110 cm in diameter (35-43 inches)—to get a perfect, thin consistency. She also mentions that the blitva (chard) needs to be dried after being washed so the dough won’t get soggy.

A wood stick and a large wood platter are the basic kitchen equipment for rolling dough.

A wood stick and a large wood platter are the basic kitchen equipment for rolling dough.

If you noticed the similarity of their names, that’s intentional. Boys’ and girls’ names are derived from their grandparents, per an old-world practice that’s still carried out.

Embers and ashes

Back in the kitchen… once the first layer of dough is covered with the vegetable mixture, a second layer is placed on top and the pie is sealed with a braided edge; ready for the oven. Then the massive soparnik is slid off the sinija and onto the hot stone. The next step made me gasp, it was covered with embers and ash. No!

Locally grown chard, a.k.a. blitva in Croatia, is the main vegetable inside soparnik and it’s carefully tripped to remove the hard stem so the thinly sliced pieces cook evenly.

Locally grown chard, a.k.a. blitva in Croatia, is the main vegetable inside soparnik and it’s carefully tripped to remove the hard stem so the thinly sliced pieces cook evenly.

Baking this way for nearly 20 minutes, the pie cooks on top and bottom and picks up a subtle smokey flavor. I appreciated this nuance when I tasted a finished piece, which had the final touches—a coating of Dalmatian olive oil and a sprinkling of raw garlic.

Dalmatian specialty

This traditional Dalmatian specialty symbolizes a specific culture and a way of life. While you eat soparnik, it’s intriguing to let your mind wander back to the Poljička Republika and try and imagine an alternate scenario where somebody else ate the exact same thing, literally, in the same place, hundreds of years ago.

The pie stuffing of chard mixed with onion, salt, and olive oil is evenly spread on the thin layer of dough.

The pie stuffing of chard mixed with onion, salt, and olive oil is evenly spread on the thin layer of dough.

The EU protection helps to make that connection because it guarantees that the soparnik you buy from local markets and festivals is authentic from Poljica.

Magic happens in a hot stone oven when coal embers and ashes bake the top part of your soparnik and add a subtle smokey flavor.

Magic happens in a hot stone oven when coal embers and ashes bake the top part of your soparnik and add a subtle smokey flavor.

Pizza anyone?

So, if you’re now wondering about another national “pie,” here’s a fun fact. Legend has it that Venetians in Croatia who tasted soparnik back in the day took it home to Italy and it became the inspiration for pizza. What do you think? Dobar Tek!

This experience was another great authentic adventure organized by the Cromads travel club.

Story and photographs ©2022, Cyndie Burkhardt. https://photo-diaries.com

Learn more at TCN’s Digital Nomads channel.