A look at the turbulent Croatian politics and history of this newly independent state. Just over 30 years old, modern Croatia has had quite a start.

- Croatian politics and history since 1990: introduction

- Tensions in former Yugoslavia

- The Serb minority in Croatia

- The Homeland War

- UN Peacekeepers, Operations Flash and Storm

- Peace and the building of a modern state

- Illness and death of President Tudjman

- Croatian politics after Tudjman

- War Crimes Tribunal

- The path to EU entry

- The global economic crisis

- Jadranka Kosor and Slovenia

- Croatian politics moves left in 2011

- Croatia enters the EU

- A new political party and an unknown Prime Minister

- A new HDZ coalition

- Plenkovic consolidates power in 2020 election

Croatian politics and history since 1990: introduction

The history of independent Croatia began in the early 1990s. Croatia entered the decade as part of multi-ethnic and still socialist Yugoslavia, which came into being in 1918, first as a kingdom under the rule of Serbian kings and later as a socialist federation after the Second World War, ruled by the Communist Party and legendary Yugoslav WWII leader, Josip Broz Tito, who himself was half-Croatian from the Hrvatsko Zagorje region and of a Croatian father and Slovenian mother.

Importantly for Croatia, Yugoslavia was a federation, a union of six federal republics which could retain some features of their statehood. While in the most of Yugoslavia’s history this was just a formality, towards the 1970s and later it became a more prominent feature of the country’s politics and eventually allowed Croatia to proclaim its independence legally, recognised by the international community. The first significant step towards independence took place in the early 1970s, with the “Croatian Spring” movement.

The Croatian leadership at the time, all members of the Communist Party, started demanding greater rights for individual republics. Numerous Croatian intellectuals, university professors and members of the public added their voices. However, their demands did not succeed, and they lost their jobs as a result, with some ending up in prison for their alleged anti-Yugoslav activities.

Tensions in former Yugoslavia

However, just a few years later, Josip Broz Tito, the undisputed ruler of Yugoslavia, realised that more rights for individual republics was the right direction. In 1974, a new Yugoslav constitution became law, which gave republics a right to self-determination. For a while, the political life in Yugoslavia came to a standstill, with everybody preparing for the post-Tito period. When he died in 1980, tensions between republics started growing, with Croatia and Slovenia, the two westernmost and most developed republics, demanding more autonomy, and Serbia trying to use the fact that it was the largest individual republic to dominate Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavia entered the late 1980s in a political and economic turmoil. When Communist regimes started falling in Eastern Europe in 1989, Yugoslavia would inevitably follow. In early 1990, the (in)famous 14th Extraordinary Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia occurred in Belgrade, which marked the effective end of Yugoslavia as a communist nation. The Slovenian and Croatian delegates on the one side and the Serbian-led delegates on the other went their separate ways, and the break-up of Yugoslavia became unavoidable.

Soon the first multiparty elections took place in each of the republics. On 22 April and 6 May 1990, there were elections in Croatia. The newly-formed HDZ, led by Tito’s former general and later Croat dissident Franjo Tudjman, winning a majority. The Communist Party went into opposition for the first time in 45 years. The new government immediately adapted Croatia’s constitution, erasing “Socialist” from the name “Socialist Republic of Croatia”. Several months later, in December 1990, a whole new constitution came into force. The same constitution exists today.

The Serb minority in Croatia

Serbs in Croatia, who comprised 12% of the population (mostly in parts of inland Croatia and Slavonia), did not accept the new authorities. They were partially under the influence of the propaganda which claimed that the new government was a continuation of the fascist Ustasha regime from the times of the so-called Independent State of Croatia in the Second World War.

While the new government was definitely not Ustasha-like, it did make moves which made the job easier for those who wanted to convince Serbs in Croatia that they should try to break away. In August 1990, Serbs started blocking roads connecting northern and southern Croatia.

The first armed conflict took place on Easter 1991, which some believe was the start of what would later become the Homeland War. In 1991, the so-called Serbian Republic of Krajina established itself in the Serb-held parts of Croatia. This eventually covered a third of Croatia’s territory.

In 1991, numerous conferences and meeting took place to discuss the future of Yugoslavia, but it soon became apparent that the country had no future and that individual republics (except for Serbia and its partner Montenegro) would try to go their separate ways. Croatia and Slovenia proclaimed their independence on 25 June 1991. And so began a short war in Slovenia and the beginning of the full-scale war in Croatia.

Under international pressure, implementation stalled for three months, until 8 October 1991. In an atmosphere of near total war in Croatia, Parliament again proclaimed Croatia’s independence. These two dates are today are public holidays: Statehood Day (25 June) and Independence Day (8 October).

The Homeland War

The Homeland War marked the first five years of Croatia’s existence as a multi-party democracy. It started for real in the second half of the year, with Serb rebels assisted by parts of the Yugoslav National Army. In four years, more than 20,000 people on both sides would die, with hundreds of thousands displaced. The worst phase of the war for Croatia was autumn 1991. Eventually, the frontline held, but with a third of territory being occupied by Yugoslav/Serb forces.

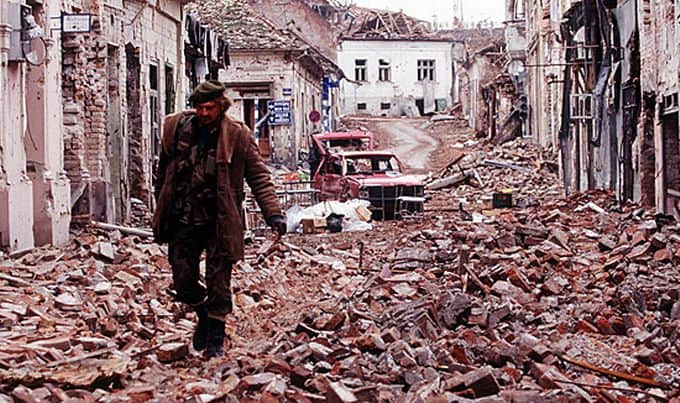

The most infamous battle of the war took place in November 1991 for the town of Vukovar in eastern Croatia. The town was under siege for months, with many civilians trapped inside. The devastated town fell on 18 November. What followed were massive war crimes against both Croatian soldiers and civilians.

The largest individual massacre took place on 20 November at Ovcara near Vukovar, where more than 250 people brutally lost their lives. This phase of the war continued for more than a month. Many other Croatian towns came under attack, most notably Dubrovnik.

Even though the international community did not immediately recognise Croatia’s independence, it soon became apparent that, partly due to the gruesome images of the aggression against Croatia, the international community would have no other choice. The critical decision came on 15 January 1992, when the European Community decided to recognise Croatia and Slovenia. In the next few months, many others followed. These included the United States, Russia, and China, and in May 1991 Croatia became a member of the United Nations. After many centuries of being part of various arrangements with Hungary, Austria and Yugoslav nations, Croatia again became an independent and internationally recognised state. What just a few years earlier seemed utterly impossible had become a reality.

UN Peacekeepers, Operations Flash and Storm

Early 1992 also brought the arrival of UN peacekeepers to Croatia, which helped freeze the conflict. While large areas of the country remained occupied, at least the number of victims decreased substantially. The fragile ceasefire would more or less hold until 1995. Croatia used this time to grow its army and prepare for the liberation. While there were several smaller military operations in the meantime, the main operations began in 1995. In early May, in operation called Flash, Croatia liberated Western Slavonia, re-establishing direct road links between Zagreb and Eastern Slavonia.

This was just an introduction to a much larger operation Storm. This took place in early August, quickly bringing the liberation of most of the remaining occupied areas. The resistance of the Serb forces was not particularly strong, and their forces withdraw almost immediately. So too did hundreds of thousands of civilians, to the Serb-controlled parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and further to Serbia.

The operation remains controversial to some to this day. While Croatia rightly describes it as the liberation of parts of its previously occupied internationally-recognised territory, Serbian government describes it as the largest ethnic-cleansing operation in Europe since the Second World War, noting that hundreds of thousands of ethnic Serbs fled Croatia, where their predecessors lived for centuries, never to return.

War in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina officially ended in late 1995, with the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement. An accompanying agreement dealt with the issue of Eastern Slavonia, which was still occupied by Serb forces at the time. It provided for the peaceful return of the area to Croatian control in early 1998. This eventually took place without further incident.

Peace and the building of a modern state

After the war, Croatia turned to domestic affairs. One problem was the economy, which was in terrible shape. This was not least because of the criminal privatisation process of state-owned companies, which happened during the war. Many companies traded hands for next to nothing to murky “entrepreneurs”. In most cases, they took the funds from the companies and sold their real estate. Unemployment was the only reward for the workforce. The effects of this organised pillage are still in evidence today.

The other issue was the democratic deficit. While Croatia was formally a multiparty democracy, in reality, Tudjman and his HDZ ran the country autocratically. One of the most infamous examples of Croatian-style “democracy” occurred in autumn 1995. The opposition had won the elections for the Zagreb City Assembly. Using a provision of the law that the president had to confirm the mayor, Tudjman rejected several opposition mayoral candidates. This was even though they had majority support. The so-called Zagreb Crisis continued for months. It ended only after HDZ managed to buy two opposition councillors, thereby gaining a majority in the assembly.

Another important event for Croatian democracy occurred in November 1996. The government tried to shut down Radio 101 in Zagreb, one of the few media outlets which criticised the authorities. The decision prompted protests, and 120,000 people took to the streets of Zagreb on 21 November 1996. The government relented under pressure, and the radio station continued with its broadcasts.

Illness and death of President Tudjman

At the same time, Tudjman mysteriously disappeared from the public eye. International media reported his disappearance a few days later. He was in the United States, receiving treatment for cancer. Although the public knew, he never admitted his illness. He also never allowed his medical team to issue statements about his health, despite him being visibly unwell.

The situation in the new few years resembled those near the end of Tito’s life. While Tudjman responded to the treatment better than initially expected, everybody wondered what would happen after him. With Tudjman getting weaker and weaker, his associates started behaving more freely. They used the opportunity to enrich themselves and use their power for personal gain while they still could. This caused widespread resentment and the growing dissatisfaction among the public. Due to this and numerous other issues, Croatia was also becoming more and more internationally.

After winning several elections during the war, HDZ now faced the genuine possibility of losing the 1999 elections. Tudjman’s health situation complicated things further. Despite all his flaws, many saw him as the founder of independent Croatia. For them, he was the reason why they still voted for HDZ. Without him, the party was in danger of losing masses of votes. This is precisely what happened. Tudjman’s last public appearance was in early November 1999. He became ill and went to hospital, where he died on 10 December. The first phase of Croatia’s independence was at its end.

Croatian politics after Tudjman

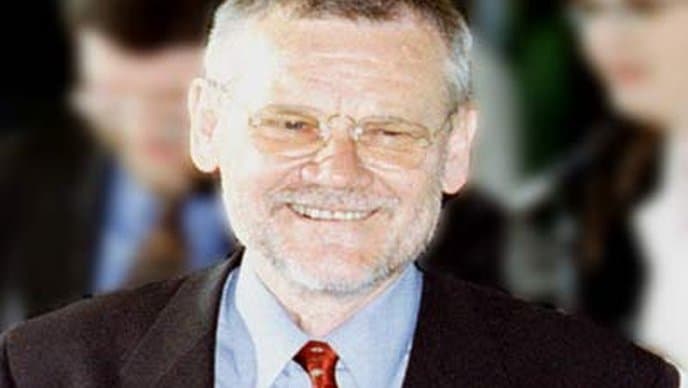

On 3 January 2000, parliamentary elections took place. HDZ suffered a heavy defeat and went into opposition for the first time. The new government comprised six opposition partners, led by SDP. It also included the reformed Communist Party, under the leadership of Ivica Racan. Racan had been the last secretary general of Croatia’s Communist Party, and he became the new prime minister. A month later, presidential elections to elect Tudjman’s successor took place. HDZ’s candidate lost in the first round, with Stjepan Mesic, former Tudjman’s associate and later sharp critic, becoming the president.

The first significant decision of the new government was to change the constitution. The aim was to replace the semi-presidential political system with the parliamentary system. At the time, the role of the most powerful politician in Croatia moved from president to prime minister. Racan’s government was weak, under pressure both from internal disagreements between the six parties. It also suffered attacks from the right-wing parties led by HDZ, which would not accept a role in the opposition. They accused the government of being traitorous and anti-Croatian. This is a well-tried recipe for anyone who dares to advocate any other opinion than the officially sanctioned HDZ one.

War Crimes Tribunal

The major political issue at this time was Croatia’s cooperation with the International War Crimes Tribunal in the Hague. While Tudjman’s government initially supported the establishment of the UN tribunal, this did not last long. The government thought initially that the tribunal would try just Serbian leaders. The Croatian government changed its opinion after it realised that the Croatian leadership would also be under investigation. The first indictments started arriving from the Hague, and the government was slow to comply. Compliance with the tribunal was not patriotic.

In 2001, a massive protest against the SDP-led government took place in Split.

Leader of the opposition and HDZ president, Ivo Sanader, accused Racan of being a traitor. Interestingly, just a few years later, after he became the next prime minister, Sanader extradited anyone the tribunal demanded, without anybody accusing him of anything.

The path to EU entry

Another important political event was the decision for Croatia to begin the process of entering the European Union. In November 2000, a large European summit took place in Zagreb, with European leaders promising they would support Croatia on its road to membership. The process formally started in 2001 with the official application but was delayed many times, due to the issues of cooperation with the Hague tribunal, lack of reforms and the relations with Slovenia. Croatia would not enter the European Union until 2013.

Under the Racan government, the economy started to recover, and one major infrastructure project began – the construction of the motorway network. In a few years, all the major towns in the country except for Dubrovnik had a motorway connection, which remains one of the few successful major infrastructure projects completed in independent Croatia.

Parliamentary elections held in late 2003 brought about a change of government. HDZ returned to power after just four years in opposition, and Sanader became the prime minister. He finished the motorway system construction project and promptly extradited everybody to the Hague, which enabled Croatia to start the negotiations to join the European Union. Under Sanader, who won another election in 2007, Croatia entered NATO, developed its economy and drew closer to the European Union.

The global economic crisis

However, in early 2009, the first signs of the impending economic crisis could be felt. Before the real crisis hit, there was a sudden and unexpected change in leadership. Prime Minister Sanader resigned without proper explanation on 1 July. The real reasons for his resignation are still awaiting proper explanation. He nominated as his successor Deputy Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor, who he thought he could control. A few months later, it became evident that Sanader wanted to remain in charge behind the scenes, but Kosor became increasingly independent.

In early 2010, he tried to depose Kosor but did not succeed. This marked the beginning of the end of his political career. Soon, articles in the press appeared alleging that Sanader had amassed immense wealth while in office. With his waning influence, various investigations and trials against him and his associates were launched. He was eventually arrested in Austria after an unsuccessful escape attempt and deported to Croatia. He spent many months in remand prison and was later released. The court proceedings are too numerous to be listed here, but not a single one of them has so far ended with a final decision.

Jadranka Kosor and Slovenia

The main task for Jadranka Kosor, in addition to fighting Sanader’s attempts to depose her, was to conclude the accession negotiations with the European Union. The main issue as the end of the process was the decision of Slovenia to block Croatia until the border between the two countries was defined.

The solution came in arbitration proceedings which should have solved the issue forever. Although Slovenia did lift its blockade which enabled Croatia to conclude negotiations in 2011, the arbitration dragged on for years. In 2015, Croatia left the proceedings after secret recordings showed that Slovenia was trying to influence the supposedly independent arbitrators.

Still, the arbitration proceeded without Croatia, eventually ending with a ruling which attempted to find the middle ground between the two sides. Now, in 2019, Slovenia is insisting on the implementation, while Croatia proposes new negotiations. Almost 30 years after the two countries gained their independence, the border issue remains unsolved.

Croatian politics moves left in 2011

The growing number of corruption affairs which hit Sanader, his ministers and HDZ meant that the party had no chance of winning the parliamentary elections which took place in late 2011. HDZ once again went into opposition and another coalition came to power led by SDP and its president Zoran Milanovic, who became the prime minister.

The new government did not seem to do much. The economy started to recuperate from the crisis very slowly on its own, in accordance with the Milanovic’s (in)famous motto: “Even if we do not do anything, something will happen.” SDP’s government was again inevitably accused of being traitorous by the right-wing groups, which again could not accept anyone else being in power.

Soon, various veterans’ associations organised a series of protests against the “Yugo-nostalgic” government, which culminated with a protest tent in front of the Ministry of Veteran’s Affairs for many months. The government clumsily tried to defend itself, including giving concessions to the protesters, but the outcome had already been deciced. It alienated its own voters without gaining new support.

Croatia enters the EU

While the EU accession negotiations ended under the Kosor government, it was Milanovic who had the honour to preside over the official entry to the European Union on 1 July 2013, undoubtedly the most significant foreign policy achievement of Croatia since gaining independence. While the expectations were high, the reality of the EU membership has been somewhat more ambiguous.

The economic revival failed to materialise, while the main effect of EU membership is mass emigration of young and educated people, who left the country in their hundreds of thousands to find a better life in Germany, Ireland and other countries. Still, there is little doubt that Croatia would be in an even worse position outside of the Union.

Another major story of the Milanovic era was the refugee crisis which hit Croatia in late 2015 when hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants from the Middle East and other parts of the world came to Croatian borders wishing to reach Germany and beyond. The government sensibly rejected proposals about sending the army to the border to stop the migrants, opting instead for organising their transport from the eastern border to Hungary and Slovenia. While the wave of migrants has subsided substantially, the debates about what to do on the borders continue.

A new political party and an unknown Prime Minister

With few results to show and under pressure from right-wing protesters, SDP lost the elections held in late 2015. While for a while it seemed they might form a coalition government with MOST, a new, hard-to-define political party. In the end, MOST as expected opted for a partnership with HDZ, but with one very peculiar condition: it insisted that the new prime minister had to be a politically independent candidate.

The solution came in the shape of one Tihomir Oreskovic, an unknown businessman who left Croatia as a child and could barely speak Croatian. With Oreskovic being just the nominal prime minister and with HDZ and MOST fighting in the background, it was evident that the government would not last. The coalition fell apart, and the government was voted out of office by the parliament, for the first time in modern Croatian history. Early parliamentary elections were scheduled for September 2016.

HDZ again won the most votes and decided to once again enter a coalition with MOST, this time with a clear understanding that the new HDZ president, Andrej Plenkovic, would be the prime minister. Still, the disagreements between the two parties continued, and the coalition once again fell apart in spring 2017.

A new HDZ coalition

However, HDZ this time managed to find a substitute coalition partner and the new elections did not take place. MOST was replaced by HNS, a supposedly liberal party which was until then a long-time coalition partner of SDP. Many understandably described this as cheating the voters, given that MPs elected by left-wing voters would now support a right-wing government. Despite a small majority in parliament, the coalition has proven to be quite resilient and managed to cling on to power until the 2020 elections.

Plenkovic announced that he would try to “de-dramatise” Croatian politics, but does not seem to be very successful in achieving that goal. He is under constant pressure from the right-wing party faction, which views him with suspicion, accusing him of being a liberal pretending to be a conservative. In return, Plenković seems too careful not to disturb the fragile party equilibrium and therefore delays making decisions on any and all controversial issues, including those regarding extremist historical revisionism, which has been on the rise in the last few years.

The main economic story of the Plenkovic’s era was a near collapse of Agrokor, the largest privately-owned company in Croatia, which found itself on the brink of bankruptcy in 2017. Under still secretive circumstances, the government prepared a special law which helped prevent the collapse and the whole affair seems to be heading to a happy ending, accompanied by inevitable scandals about who and how profited from the operation. While a deputy prime minister had to resign, Plenkovic survived the scandal mostly unharmed.

Plenkovic consolidates power in 2020 elections

The 2020 general election took place against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. While Plenkovic was fighting that battle and his traditional SDP adversaries, a strong challenge also came from the right, from Miroslav Skoro’s Homeland Movement.

Opinion polls indicated that it would be impossible for Plenkovic to form a government without a coalition with Skoro, but on the day, the SDP vote failed to materialise as expected, and Plenkovic was able to form a tight majority with the aid of minority parties, thereby excluding Skoro.

At time of writing (March 2021), the pandemic continues to dominate politics, as does the growing discontent of the private sector through the increasingly vocal Glas Poduzetnika (Voice of Entrepreneurs Association). The devastating earthquakes in Zagreb (March 2020) and Petrinja (December 2020), as well as the sudden death of long-time Zagreb mayor, have also contributed significantly to political developments.

While it is hard to predict what the future will bring, we can only hope that the next three decades of Croatia’s independence will be more successful and less dramatic than the first.

For the latest in Croatian politics, follow the dedicated Total Croatia News section.