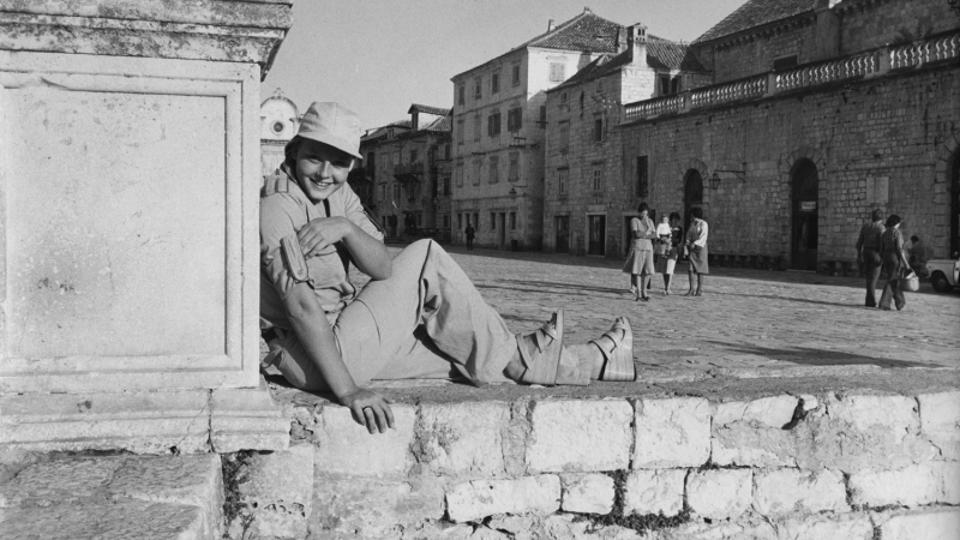

These days, celebrity photographer Jadran Lazic can be found at home among his beloved lavender fields on the island of Hvar, reflecting on a glittering career being the camera spanning over 50 years. In addition to snapping some of the world’s biggest names, he has also racked up some impressive world exclusives over the years, as well as befriending several celebrities – it was Lazic who brought a young Jodie Foster to Hvar for a holiday back in the 1970s, for example.

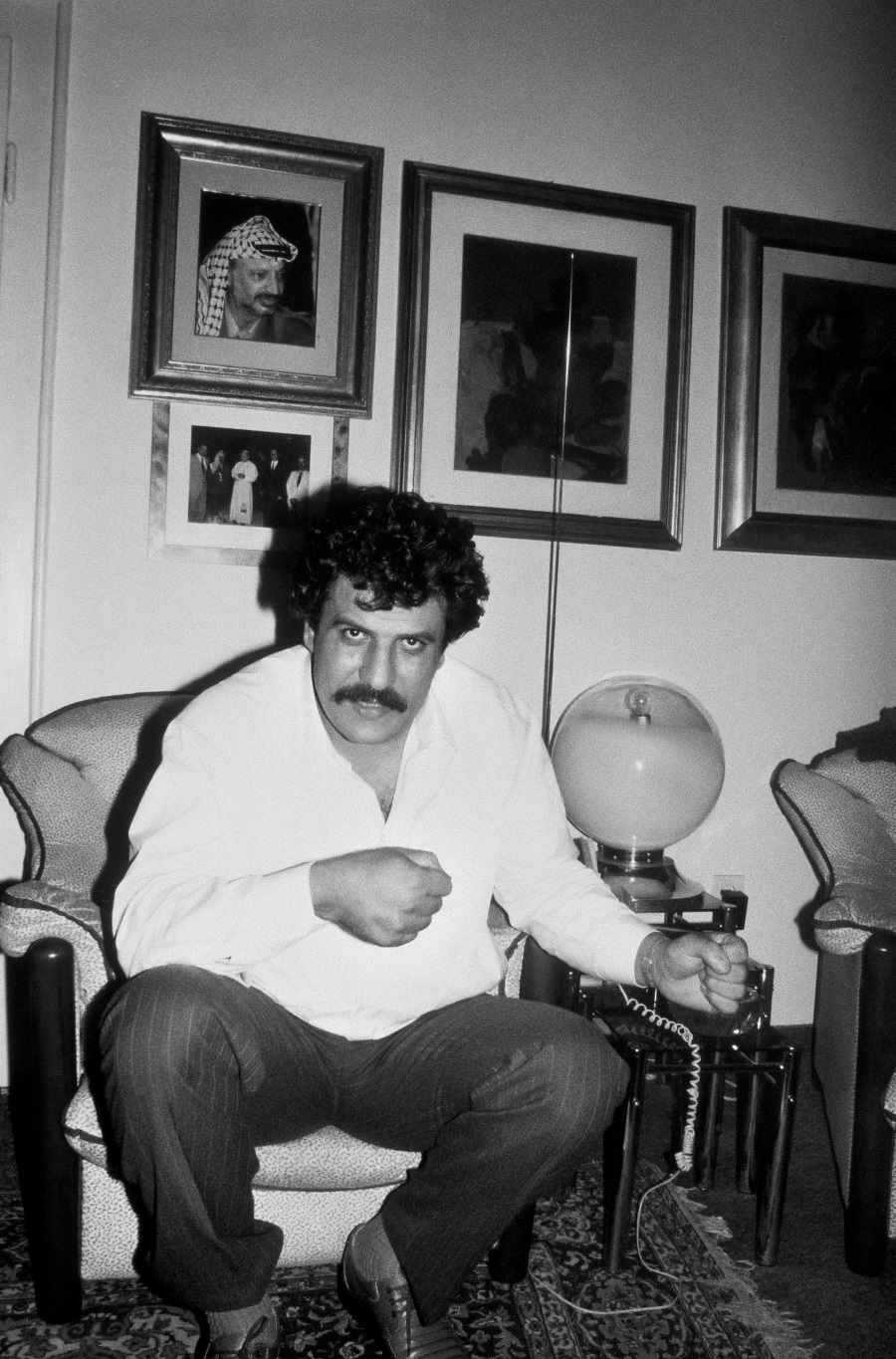

Earlier this year, TCN covered the extraordinary story of how Lazic tracked down and photographed wanted Palestinian terrorist and architect of the Achille Lauro hijacking, Abu Abbas, to a Belgrade apartment.

That exclusive took place in 1985, some three years after perhaps an even bigger achievement – the only photos by a Western-accredited agency from the Leonid Brezhnev funeral back in 1982. Photos which would sell for an impressive US$300,000 in 1982 currency (almost US$850,000 today), and would enable the Split snapper to buy his dream home on the water in Zavala on the island of Hvar, where he divides his time with Los Angeles and looks after his olive and lavender fields. As with the Abu Abbas story, Lazic’s success was a mixture of charm, determination, ingenuity, and luck.

Lazic was living in Belgrade back in 1982, working for Paris-based photo agency, SIPA. Communications back in those days were a world apart from the instant digital age of today, and he did not even have a phone in his apartment, which was a major disadvantage for a breaking news photojournalist. As such, he tended to hang around the post office a lot to have better access to communications.

A few weeks before the Soviet leader died, things were fairly quiet, and Lazic decided to be proactive in creating stories to cover. From the post office, he called his boss in Paris and they agreed that he would try and cover the upcoming annual October Revolution Parade in Moscow. This was the height of the Cold War, and Western media access was restricted, but entry for citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia was a lot more relaxed. Lazic was unsure whether or not to apply as a local freelance reporter or an official SIPA photographer. He made the wrong choice with the SIPA route, and his request was politely declined, as it would now be if he applied the same way in the future.

(Jadran Lazic today, with the author. The only association to th Hammer and Sickle these days is during the annual lavender harvest on Hvar)

A few weeks later, he was driving his daughter to her Belgrade kindergarten, when he heard the news that the Soviet leader had died. He knew that he had to go and cover the event and headed straight to the post office to get permission from Paris. With official approval from France, now came the tricky bit – how to get permission to enter Russia after his recent unsuccessful embassy application?

Lazic called the editor of a Yugoslav magazine and asked if they would be interested in sending a reporter to cover the story if he accompanied the journalist, covered his own costs, and gave his photos to the magazine for free, in return for a letter naming Lazic as the accredited photographer to the journalist. The editor agreed, a business visa was obtained, and both were on the next flight to Moscow from Belgrade with Aeroflot at 10:30 the following day.

The plane never reached its destination. A rough flight with plenty of turbulence was eased somewhat by the bottle of scotch the two of them shared on the flight, but it was clear from the constant turning that something was wrong, and the flight time was a lot longer than advertised. There was no announcement from the flight crew, and all was only revealed with the plane finally touched down at… Kiev – Borispol in Ukraine.

The official explanation for the diversion was bad weather in Moscow, although it was more likely due to the chaos surrounding the impending Brezhnev funeral and its logistics.

Lazic was feeling uneasy. He was technically in the Soviet Union, but probably several checkpoints away from his end destination of Moscow. Prior to his departure, Paris had informed him that no foreign journalists were being allowed in, and so the agency was depending on him. As one of the only (perhaps the only foreign-accredited photographer), this could be a huge opportunity for the agency.

His colleague passed through without problems and was seeing striking up a conversation with two ladies while Lazic awaited his turn anxiously. The USA visa in his passport elicited a frown from the border guard, who called his superior. Lazic produced the letter from the Yugoslav editor and sweated while they pored over it and discussed his fate. Having searched his things and gone through the papers and magazines he was carrying, and having checked how much money he had, they let him through.

His colleague had not been idle in the meantime. By chance, one turned out to be the wife of the Sarajevo daily, Oslobodjenie. She was to play a crucial role when they finally landed in Moscow at 10pm that evening.

Moscow was chaos. There was no press centre to help arriving journalists, so finding accommodation was going to be a challenge at this late hour. Even more so as there were no taxis and the last bus into the centre had long gone. As her husband was currently in Belgrade, the Sarajevan wife kindly offered them both a place to stay, and a lift into town was secured by his colleague, who managed to find a Japanese trade representative with enough space in his Lada for all of them. The Brezhnev funeral was one step closer.

Arriving at the apartment at 1am, there was no time for sleep. Representatives of the official Yugoslav news agency, TANJUG were also living in the building, and Lazic got into earnest conversation to see how he could get to Brezhnev. The TANJUG team was very pessimistic about his chances, given that they themselves had only received one funeral pass from two applications.

Thanks to the help of their new TANJUG friends, a letter of recommendation was procured from the Yugoslav Embassy in Moscow, which brought the Belgrade Two to the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Every now and then, one did encounter a friendly and helpful public official in the Soviet Union (I encountered three in my time there), and Lazic had a slice of luck in this case.

The official said that their chances were slim, but he would see what he could do, advising them to head to the Trade Union Hall with the permanent correspondents, where Brezhnev’s body was lying in state. The official would then inform the staff there to let them enter.

They were driven to the Trade Union Hall by the permanent correspondent of Yugoslav daily, Borba, who was well-versed in negotiating checkpoints and the Soviet bureaucratic system. And upon arriving, they were welcomed by a friendly face – the helpful official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Not only did he instruct the staff to let them enter, but he assigned two security officers to take them through the back corridors to avoid the line of journalists so that they could see Brezhnev lying in state alone.

“You have one minute, then you must leave.”

Snap. Snap. Snap. Lazic got to work, shooting as much as he could in the short time allocated, and ignoring pleas to stop and to leave. He would only stop when they physically removed him, which they did after a couple of minutes. He had got the first part of his exclusive. How he would get the pictures to Paris was a problem to be resolved in the future.

While he had great shots of the body lying in state, by jumping the queue, he had missed the chance to shoot the late Soviet leader’s family, but he got his chance the following day. The following day also started brightly for another reason, as one of his new TANJUG friends had somehow managed to obtain a pass for Lazic for the Brezhnev funeral cortege.

Security was tight, and nobody without a pass could enter within a 4km radius of Red Square. After endless checkpoints, Lazic eventually reached Red Square which was already filled with mourners. Trying to get closer to the mausoleum proved impossible, as security guards were blocking everything. Even the offer of a US$100 for a guard to look the other way failed. In desperation, Lazic retreated and climbed to the highest point he could in one part of the square. He would have only a moment to shoot as the cortege passed, and the shot would be through a crowd so would require some skill, but it was the best he could do.

The Brezhnev funeral cortege moved slowly towards its end destination of the Kremlin necropolis, but there was still only time for 5-6 shots. And having taken those, his job was done. While everyone else continued to take part in the funeral, Lazic had a plane to catch to Belgrade, and photos to send to Paris.

But first he had to get through the checkpoints of the Soviet authorities. He knew he had a bombshell, which would please his bosses in Paris, but he was not sure how Soviet border guards might feel if they discovered what he had with him. He decided to take some precautions.

Back at the apartment, he wrapped the precious film in aluminium foil and put them in the carton boxes for unused film rolls, then put the unused rolls into his cameras to pretend that they were already exposed. This was a precaution against X-rays and a border guard’s decision to destroy the film in his camera.

His journalist colleague Slavko went first and passed through without a hitch with his luggage. Lazic was panicking internally, but started to relax once his luggage too passed unhindered. He was almost home, but it turned out he started to relax too early.

BEEP! Much to his surprise, as he had no metal on his person, the scanner beeped and he was frisked. After some time, an offending nail clipper was found in his jacket – it must have slipped through a hole in the pocket.

The nail clipper may have been an innocent explanation, but that did not mean that the Soviets were convinced of his innocence, and he was taken to a room for questioning. Foreigners visiting the Soviet Union were required to report the amount of foreign currency they had on entry and departure, as well as receipts from any official purchases. This was done to control illegal exchange to roubles in the black market, where the exchange rate was much higher.

Lazic showed them the money he had, as well as the official receipts for the two fur coats he had bought for his daughter from the beryoska hard-currency store, but he did not have the declaration from his arrival in Kiev. In all the confusion, it had been overlooked.

The border official left the room to consult with his superiors.

And then, a moment which required a dramatic and fateful decision. Looking through a curtain, he saw his bag a few metres away. Ten steps from there, the tunnel to the Belgrade flight. What the hell, he thought. If he could at least get the film to Slavko to forward to Paris, his trip would not be in vain. Confidently, and without a second thought, he strode out, grabbed his bag, and headed down the tunnel. He was waiting for a shout, a whistle, a firm grip on his shoulder from a guard.

But there was none.

Aboard the plane, he quickly informed Slavko what would be required of him, in case the Soviets boarded the plane:

“In case they come for me, take these films. Here’s the address of Sipa Press. When you arrive in Belgrade, send the films to Paris as soon as possible!”

No border guards boarded the plane, and after a few anxious minutes, the cabin door closed, and soon they were airborne. Destination Belgrade. He had done it.

Almost.

Belgrade was not Paris. The usual protocol for getting his film to Paris was to go to the airport, find a sympathetic-looking passenger and ask them to carry the film to Paris, where a SIPA representative would be waiting at passenger arrivals. Hardly a system that would work today…

Although the system worked very well, the stakes were higher with this assignment, and Lazic decided to fly straight to Paris, accompanied by the film and his daughter’s fur coats. He had something the world wanted to see, and time was of the essence.

He knew that he had something very valuable, but it was only on arrival that he realised quite how valuable. Usually, the agency sent a courier to collect the film from the airport, but Michel Chicheportiche, the agency’s head of sales and the director’s most trusted lieutenant, was there to meet him. THAT had never happened before.

When he confirmed he had the films with me, Chicheportiche excused himself and went to the nearest payphone to call his boss. Three minutes later he returned with a generous offer:

“The boss is offering you his personal Mercedes in exchange for the film.” Quite an opening offer, and one which the man from Split was prepared to play with.

“What good for me would a Mercedes with French license plates be in Yugoslavia? The customs duty and vehicle registration alone would cost me as much as another Mercedes.”

Another visit to the pay phone, short conversation, and then enhanced offer. The boss would cover all the costs of customs, registration, and taxes.

Now Lazic was sure he was onto something. Declining the latest offer, he suggested that they head into town and negotiate directly with the boss, settling finally on a 50/50 split of the proceeds of the sale of the photos.

As the only Western-accredited photographer there, the photos were sold all over the globe, and young Lazic was handsomely rewarded for his efforts.

And that is how the story of the Hvar’s most beautiful lavender field started.

But that is another story…