May 28, 2018 – The Adriatic, a cool beer, a pocket notebook and ruminations on laziness.

The first day at new job shouldn’t be this easy. Can this “fjaka” save us, or send us hurtling to socio-economic doom?

“I think a little series on the realities of living on a remote island would be pretty fascinating.”

– Paul Bradbury, TCN founder & my new/latest boss

An expanse of Adriatic blue reflects the mid-morning sun. The day’s paper rests to my left. A cool beer bubbles next to my right hand. I’m occupying a solitary barstool in one my village’s two cafes, scribbling my inaugural Total Croatia News piece into a well-worn pocket notebook.

Been a part of the workforce for the better part of 16 years; can’t recall a similar First Day On The Job. Perversely, new colleagues (and The Boss) encouraged this.

Have I found some sort of professional bliss? Am I lucky? Or have I succumbed to a peculiar Dalmatian quirk?

Locals here call it “fjaka” [pronounced ‘f-ya-kah’], a seemingly-carefree mindset unique to these rugged hillsides and crystalline waters.

TCN has covered it extensively; so has the BBC.

“Fjaka” has no English equivalent. It’s often defined as a “sublime state in which a human aspires for nothing.”

Recent headlines arguably showcase some “fjaka” overkill overtaking Croatia. Parliament’s schedule has more holes in it than Vukovar’s water tower. Seasonal service industry jobs along the coast remain unfilled. Foreign investors often leave in a huff.

Many blame apathy, corruption, the ever-present “Balkanizam”.

The economist John Maynard Keynes believed advances in productivity and ensuing abundance would force people to cut back their hours at work and enjoy more hours of “leisure.” (If you just laughed at the thought, you’re not alone.)

Have Dalmatians infected Croatian society with a strain of Keynesian utopia — arguably the last in the world? Could “fjaka” be the culprit?

I’m mulling all this, beer in hand, when along comes Mladen: mechanic, carpenter, campsite operator and ad-hoc boat repairer. Profitable skills in these parts. His schedule’s full of work and deadlines.

I ask him to define “fjaka.”

“That’s impossible,” he said, his hair still wet from a casual swim. “It’s undefinable.”

The conversation quickly switches to the broad spectrum of things he’s recently accomplished — fixed a boat’s cabin, prepped another for painting, installed new floors in his campsite bathroom. Then, his grand list of half-finished work. “Yeah, I should really get on that,” he says.

Mladen orders a large macchiato, lights a cigarette and launches into a broad dissertation on modern boat enamels, wood vs. plastic, and the lost art of using tar to seal hulls.

I’d like to emphasize, it’s about 11 a.m. On a Monday.

“Fjaka” looks like laziness and irresponsibility to those on the outside or receiving end. Employers, strivers, diaspora, disapproving parents, the overworked and underpaid masses all dismiss the mindset as brazen laziness, childish yet impressively casual.

“A lot of people say it’s a remnant of socialism,” Mladen mutters.

The barkeep, a 17-year-old seasonal hire from a town near the border with Serbia called Tovarnik, listens on. I ask if he’s heard of “fjaka” in Slavonia, Croatia’s northeastern region. They were, after all, socialists too.

“‘Fijaker’? That’s a carriage you tie to horses,” he responded, self-assured.

Of course he’d say that.

Before Croatia became a nation of tourism junkies, its chunk of the ever-fertile Pannonian Basin in the northeast was a breadbasket. With it came wealth and a still-thriving work ethic so strong it’s driving thousands of frustrated underemployed Slavonians to foreign lands looking for jobs.

Meanwhile, the part of Croatia most recognizable to the wider world was, until very recently, a veritable hell. Dalmatia’s arid, rocky terrain locked in by mountains and harangued by the bura wind was an economic No Man’s Land. Most Dalmatians — especially islanders — led objectively miserable lives (foreign aristocrats notwithstanding).

Progress? Nonexistent.

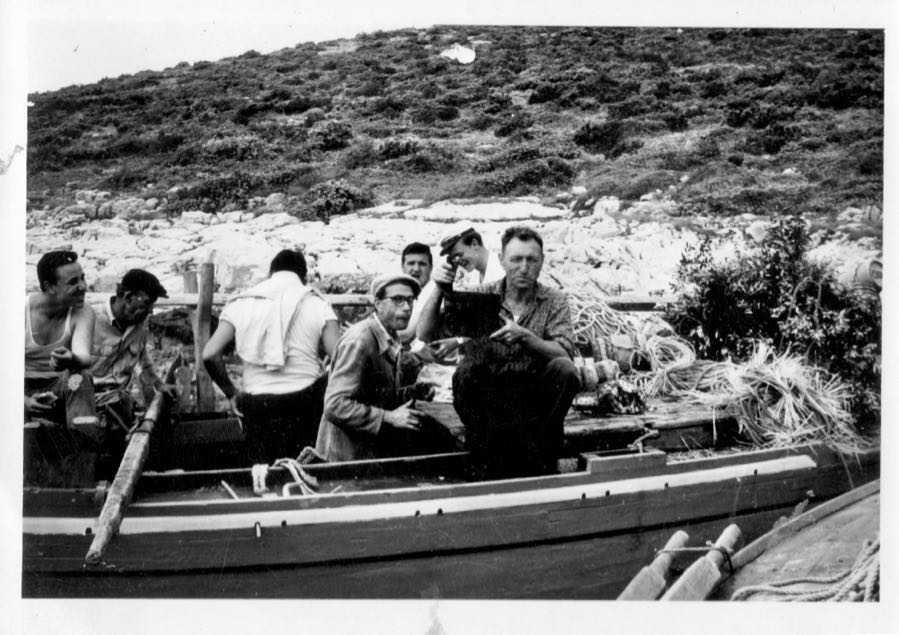

Iž, the island I call home, didn’t get electricity until the 1960s. The first blacktop road connecting the island’s two main settlements arrived in 1996. Landline phones followed a few years later.

My grandfather, for example, grew up without a kitchen table; food was prepared and eaten off the floor in a space sometimes shared with livestock (on the rare occasion they could afford a goat or lamb). The upper floor of the house was only accessible via a wooden ladder propped up against a window.

My grandmother’s family, 20-plus in a single home, survived prolonged WWII-era poverty by eating boiled oak tree acorns. Her education ended halfway through grammar school, when she became old enough to swim to a neighboring islet to herd sheep.

Ambition didn’t exist in those conditions. Meritocracy — the belief your effort alone determines your economic status — cannot take hold in a society well-acquainted with the twin harbingers of fate: Luck and Misfortune.

Fjaka remains a holdover of this era. Not to “aspire for nothing”, but to navigate life so you can greet the next morning. And perhaps enjoy a moment or two.

Fjaka rearranges your priorities, culls your to-do list and removes all unnecessary distractions. It nixes the misguided inclination to stay an extra hour at work, but keeps your child’s appointment with the pediatrician.

Ensured survival transformed fjaka into an orphaned philosophy. It never accounted for abundance and ambition, ignoring them wholesale. How liberating.

It gives one the courage to quit an awful seasonal job, wasting time earning money to buy things one doesn’t need.

Or, it lets your opening salvo at a new writing gig morph into an admission you’re struggling with a perversely beneficial inertia.

Today, pop-science gurus and modern swamis call this liberation “mindfulness,” and overcharge for apps and speeches telling people to focus on what’s important. To induce “fjaka.”

But this Dalmatian utopian mindset? It probably won’t last long.

Iž and other underpopulated islands like it remain a veritable hell to those enamored with the trappings of modern life. You know, the sort of bores whose only conversations are a laundry list of things they own, and what they do to afford them.

I’m one of the rare non-geriatrics calling this jagged little rock my full-time home. And I may be among the last.

Because all the fjaka in the world, it seems, can’t destroy the need for more, more, more, more. (Even I make concessions; I ditched the pen and notebook for a keyboard and screen at about the eighth paragraph of this story.)

Still, it’s nice to remind yourself all you need is a beer and a notebook. If only for a little while.