January the 31st, 2024 – Travel journals have always been a fairly popular form of literature in which travellers recorded their impressions of all the places they visited. Here are some impressions of Croatia from travel journals of times long gone by.

As Nikolina Demark writes, the Croatian coast played a major role in travel literature from the 15th century onwards. The powerful status of Venice and its location on the Adriatic made it a focal point of every itinerary; travellers either embarked from Venice or passed through it on their way southeast. As Venice ruled the Croatian coast until the end of the 18th century, its major cities such as Zadar or Trogir were essentially must-visit destinations for every person that travelled by sea.

Some were pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land, some were artists capturing breathtaking landscapes and grand classical monuments. Most travel journals include detailed descriptions of the places visited, their geographic position and historical background, architectural landmarks of special importance…

…and food, and wine, and women. It’s Croatia, after all, and while it doesn’t come as a surprise, it’s delightful to read about someone fawning over olive oil or the beauty of Dalmatian women centuries ago.

Back in college, I studied quite a few such journals for a paper on architecture, and I recall having a laugh every time a 17th century ‘tourist’ opted to ignore the landmarks and mused where to buy wine instead. Detrimental to my paper, but quite fun to read – and having a different outlet now, perhaps it’s time to bring those moments to light as well. After all, travellers in history weren’t that different to us today: they took in the sights, sampled the local cuisine and took interest in locals and their customs. And of course, followed it all with colourful commentary.

***

We’re starting our trip in Istria, retracing the steps of French archaeologist Jacob Spon, who stopped in Rovinj on his way from Italy to Greece in 1675:

Rovinj is a small town (…) where the land is rich in vines and olive trees. The wine is good, and I believe that to be the reason why you see so many lame people around, because strong wine is the father and the fosterer of gout and sciatica. The women wear hoop skirts in Spanish fashion which make them look appalling.

Says this man:

Looks thorougly unimpressed – alright.

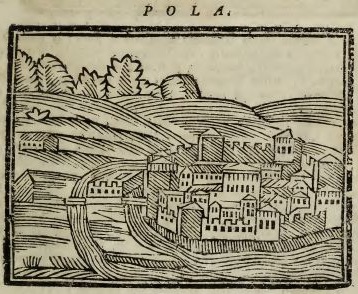

On to Pula, where Spon maintains the same level of snark:

At present it has seven or eight hundred inhabitants at most, and if it weren’t for the remnants of its ancient grandeur, no one would believe this used to be a Republic, as I learned from an inscription carved into the base of a statue of emperor Severus, where it’s referred to as Respublica Polensis.

To be fair, I can see where Spon is coming from, as Pula wasn’t exactly a lively town in the 17th century. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city gradually sank into ruin, ravaged by one attacking force after another, as well as several deadly diseases that decimated the population. It was only in the 19th century when Austria took hold of Pula that the city finally began to thrive after centuries of neglect.

But I’m getting ahead of myself; first, another visitor in the 1770s, a friar named Noé Bianchi who made a stop in Pula on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Much friendlier than Spon, he records a short yet favourable impression of the Istrian city:

It was a very noble and royal city in the past; in it resided an Emperor of Rome who had a beautiful castle built, which is now ruined but a piece of it is still visible, and some beautiful tombs still remain, sculpted in very good marble. Here we stayed for four days waiting for calm seas and good wind, then we left for our voyage and arrived in Zadar.

Slightly reminiscent of a third grader recounting his summer adventures for a back-to-school assignment. I’m a bit unclear on whether Bianchi simply referred to the amphitheatre in Pula as a castle/fort, or if he failed to notice the gigantic edifice at all in the four days he spent in town. Perhaps the latter, as we don’t see the arena in this little tableau he made:

Giuseppe Marcotti didn’t make the same faux pas upon his visit to Pula in the late 19th century. A prolific Italian writer and journalist, Marcotti gives an account of the Croatian coast in his work ‘The Eastern Adriatic: From Venice to Corfu’ that is so incredibly detailed, it reads more as a modern travel guide. It’s complete with train schedules and prices, lists of hotels and, most importantly, restaurant recommendations.

At the time of his visit, Pula was thriving under Austro-Hungarian rule as their main naval base. Marcotti notes the city is teeming with armed forces, but points to something else as Pula’s most captivating feature:

…despite the imposing ensemble of armoured towers, forts, batteries, embankments, barracks, gunpowder magazines, warehouses, factories, artillery and ammunition depots, and bays full of warships; in spite of the arsenal, all the armament and military equipment, the monuments to Roman grandeur in Pula are so remarkable, it’s them that attract the traveller’s attention above all else.

Poetic – love it.

Marcotti provides a comprehensive account of every nook and cranny from Umag to Dubrovnik, including some towns and villages not often visited in his time.

Novigrad, for example, apparently wasn’t as pretty of a sight as it is today:

Poverty and decadence are the essence of this place: carved stone and Roman tombstones were used to build small rustic houses; medieval fortifications were adapted into petty dwellings. (…) These days, the quiet port only serves as refuge from bad weather, and people only work at the stone quarries.

Let’s see what he thinks about a couple of other places in Istria – see if you can spot a common denominator in some of his impressions:

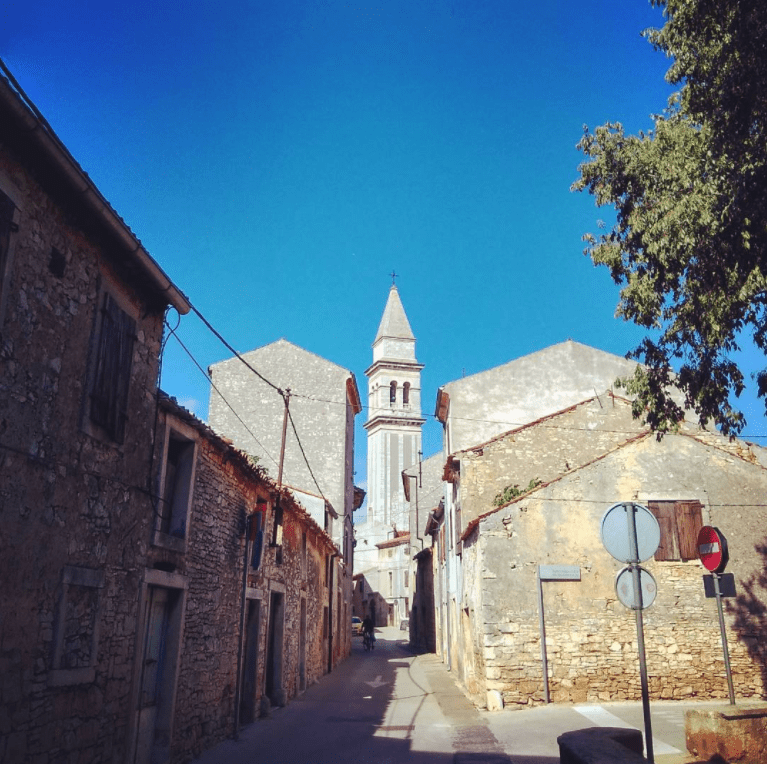

Rovinj – The labyrinth of alleys leading to the cathedral, snaking between humble houses bristled with colossal, bizarre chimneys like those in Venice, is abuzz with an energetic, fiery population which always gave the best among excellent Istrian sailors. The women appear to be a refined group of brunettes in the Venetian type; they speak, look, dress and walk as they do in Venice, typically wrapped in black scarves: their dialect is not without some Neapolitan inflection.

Vodnjan – The women inspire admiration, their distinctive beauty being that of the Latin type, with elegant limbs, well-shod and well-dressed and well-coiffed in their special attire, in many ways similar to the famous Arlesiennes of Provence – and also deserving of attention are the wedding customs, religious processions, dances and other popular festivities.

What about the men, Marcotti? We’ll never know.

Marcotti also warns you’ll have some trouble with logistics if you have your heart set on island hopping:

If you wish to visit the islands as well as the most interesting places on the mainland, you should keep it in mind that, despite the numerous steam liners of the Lloyd and the Hungarian-Croatian Society, the services are not so scheduled that you could avoid wasting a week. For this reason, and to make your stay more comfortable, it is more practical to go to Rijeka with a direct steamer from Pula (or by rail from Trieste), and then take various trips from Rijeka to visit places on the coast of Istria, Kvarner, Croatia and the islands that are discussed in this guide.

**

And finally, Pag, an island known for many things: its cheese, lamb, salt, lace, and the otherworldly landscape that is said to resemble the surface of the Moon. Although Pag isn’t part of Istria and Kvarner, we’ll cheat a bit as it’s a good point between the Northern Adriatic and Dalmatia to end this piece with.

A lengthy description of Pag comes from Alberto Fortis, an 18th-century Venetian monk, writer and cartographer who travelled in Dalmatia and recorded his impressions in a series of letters to his esteemed acquaintances, published in the 1770s as a work titled ‘A Journey to Dalmatia’ (Viaggio in Dalmazia).

Fortis was a meticulous observer and his writing detailed and extensive; as such, his letters are a phenomenal source for anyone interested in the history of Dalmatia. He gives a comprehensive account of Pag’s history, demographics, climate, economy, culture and so forth; the bulk of it is level-headed and mostly neutral, but towards the end, Fortis brings down the hammer, leaving only scorched Earth in his wake:

People’s conduct on Pag is quite uncivilised, and superstition reigns among them. (…) I haven’t found a single medallion, inscription, manuscript, nor a single sensible man in this entire town; they’re all interested in salt harvesting and whoever doesn’t talk about salt is given little regard.

They say the island’s been abandoned on several occasions, and truly, one should sooner be amazed it’s inhabited in the first place, as the lucrative salt factories are the sole thing that could inspire people to live in such a joyless place.

Ouch.

He goes on, this time in more detail:

Owing to difficulties that arise on the journey to Pag town and inadequate accommodation that foreigners come across, this place is very poorly visited. Thus its inhabitants are brutish and rude, as if they lived at the farthest possible distance from the sea and didn’t trade with decent folk. Noblemen who are under the impression they carry themselves differently than the common folk are truly laughable characters, with their attire and habits and insulting boasting. The clergy’s ignorance is unbelievable; a priest of the highest rank, believed to be a learned man, didn’t know the Latin name for Pag.

Fortis continues to fire on all cylinders, next turning his attention to folk beliefs in a criticism heavily underlined with contempt for the local clergy. Keeping in mind he was a clergyman himself, this was very 18th-century-enlightenment of him:

The majority of Pag’s population makes a living from sea salt harvesting and is paid well by the Government, which is why dry summers are of great importance to the town’s inhabitants, so much so that the uneducated folk believe the rain to be a pestilence brought upon their land by some sorcery. In line with this belief, they choose a friar to drive away the evil spirits and turn the rain away from the island. If, in spite of the poor friar’s efforts, the summer turns out to be rainy, he loses his reputation and his living; but if two or three summers in succession just so happen to be dry, the friar earns considerable respect and benefit.

In Novalja, where they deal in something different to salt harvesting, they employ equally ridiculous means to summon rain as their neighbours do in trying to keep the weather dry. There’s no end to superstitious beliefs among those poor uncivilised island folk, beliefs that are mostly encouraged and supported by friars for their own gain, and sometimes for a more nefarious purpose, but since not much good can be accomplished by bringing up folk nonsense or the wickedness of the clergy, I will leave them in peace such as they are.

1/10, would not recommend? This would be a tough act to follow, so we’ll leave it at that, much like Fortis left the Pag folk in peace… after shredding them to bits.

Next up: Dalmatia! We’re heading to Zadar, Trogir, Split and a few southern islands to see what the travellers of yore thought about some of the most popular tourist destinations in Croatia in the present day.

Sources for Part I:

Jacob Spon, Voyage de l’Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grece, et du Levant, Fait és années 1675. & 1676., Tome I (Antoine Cellier le fils, Lyon, 1678)

Noé Bianchi, Viaggio da Venezia al S. sepolcro, et al monte Sinai (Remondini, Bassano, 1770)

Giuseppe Marcotti, L’Adriatico Orientale, da Venezia a Corfu (1899)

Alberto Fortis, Put po Dalmaciji (Globus, Zagreb, 1984)

Quotes translated from Croatian, Italian and French by the author of the article.